The energy crisis sparked by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a geopolitical shock for Germany and Europe that may threaten their long-term climate policy agenda of decarbonization. Until now, Germany has managed to reduce emissions by around 35 percent since 1990, largely without carbon leakage (cutting emissions by shifting production abroad). Now, high energy prices due to Russia’s weaponizing of gas deliveries to Europe have pushed companies to move energy-intensive industrial processes abroad. These shifts may well be long-lasting, especially as energy prices are set to remain significantly above pre-crisis levels. The coordination of domestic and international policies is urgently needed to ensure that the EU and member states are positioned to continue emissions reductions and pursue their climate policy goals.

The Energy Crisis: Delinking Production from Consumption?

Even though Germany’s household and industrial sectors have achieved significant gas savings since the beginning of the crisis, anecdotal evidence collected by the economist Ben Moll indicates that part of these savings were achieved through carbon leakage, as Germany shifted its most energy-intensive industrial production abroad.

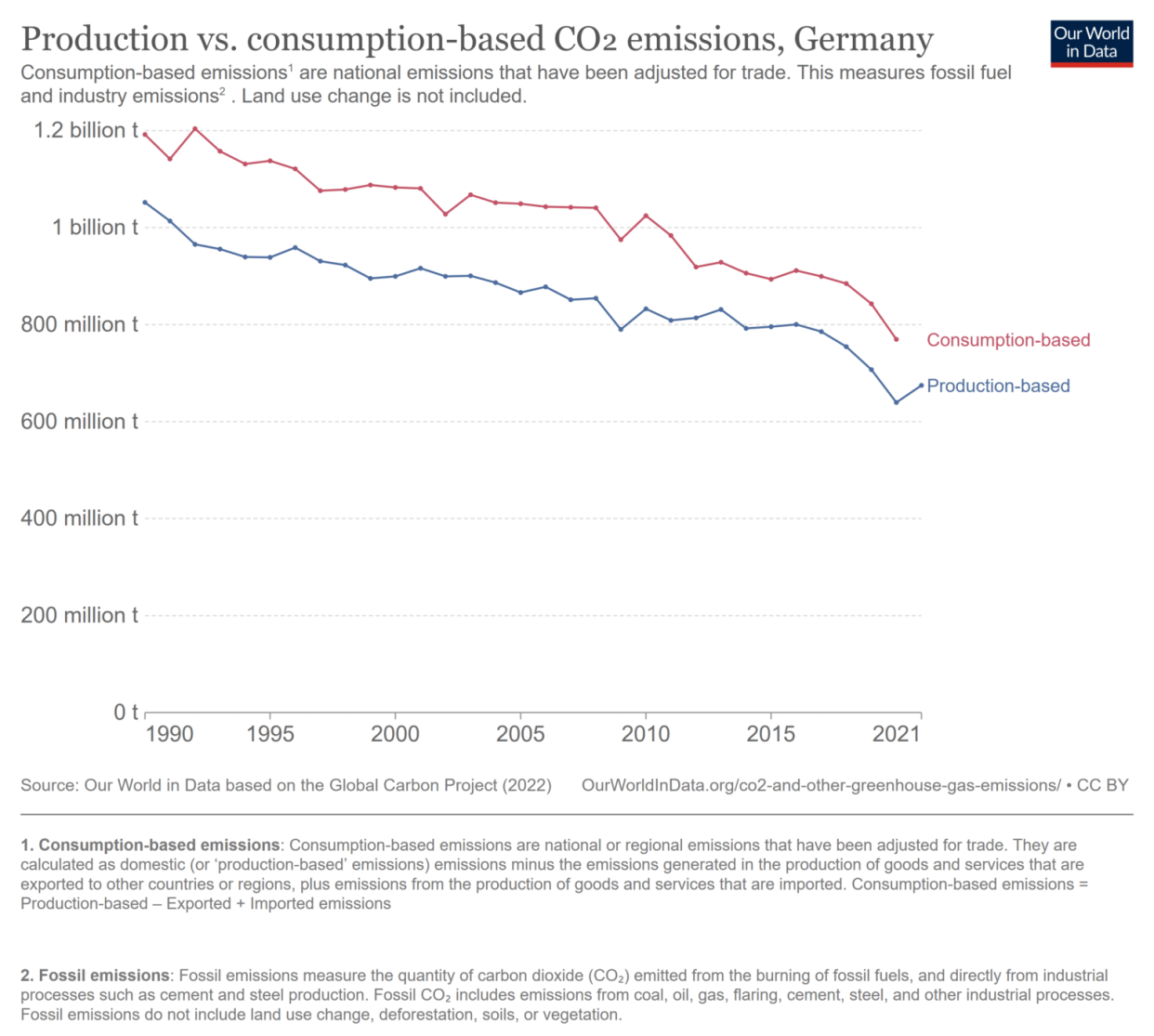

Germany’s climate protection has until now not been achieved with emissions outsourcing. This trend is also true of the 27 EU member states as a whole. The country’s CO2 emissions have been decreasing over the past three decades. This holds true both for production-based emissions (those caused by fossil fuel consumption and industrial production) and for consumption-based emissions (emissions that are caused by domestic consumption and thus include ‘imported’ emissions). Production-based emissions have declined from 1.05 billion tons of CO2 in 1990 to about 639 million in 2020, while consumption-based emissions declined from 1.19 billion tons in 1990 to 769 million in 2020 – each a reduction of about 35 percent. Thus, Germany’s decarbonization (including industry) has not been achieved at the cost of carbon leakage or importing goods with a higher carbon emissions footprint.

But the energy price shock may change that. Natural gas is an important primary energy source for Germany and especially relevant as an input for high-intensity production processes. Since the crisis, some parts of the chemical industry, for example, have considered moving such production abroad. Producers of industrial products such as ammonia used for nitrogen fertilizers and certain plastics have also been affected.

Shifting production of these items abroad would be unlikely to cause large-scale economic damage. A recent study by the Halle Institute for Economic Research showed that the vast majority of German industry demand for gas (90 percent) is used to produce a relatively small number of products (about 300 items). In fact, substantial adjustment of energy consumption at relatively limited economic costs appears possible, especially since extreme price volatility has eased somewhat and initial fears of a national economic breakdown have subsided.

By reducing domestic emissions, such outsourcing of carbon-intensive production might give the appearance of accelerating Europe’s decarbonization. But from the perspective of global emissions, it is a case of carbon leakage that has not occurred with previous climate policies.

International Climate Action Becomes More Urgent

The relocation of energy-intensive production abroad increases the need for international climate action and reduces the effectiveness of domestic climate policy. In fact, the gap between consumption and production-based measures of emissions is set to increase. As European climate policies will become more stringent in the coming years, the importance of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) – a levy on some carbon-intensive imports to discourage leakage – and other international climate policies grows. For these climate policies to be effective, the EU and its member states must jointly address both the domestic and foreign policy dimensions of industrial transformation.

Domestically, policies need to ensure that investments enhance independence from fossil fuels, rather than further postpone their phase out – or worse, lock them in even further. In this regard, recovery funds allocated to industry during the COVID-19 pandemic are a reason for caution. While in Germany little funding was channeled directly to fossil fuel industries and the focus was on support for hydrogen production, an overall European assessment of recovery spending in the industry sector shows that EUR 20 billion (about 36 percent of all industrial recovery spending) is likely to have been harmful for the green transition. In times of multiple crises, governments tend to focus on short-term fixes, thereby reinforcing path-dependencies and delaying structural change. While some spending on existing fossil infrastructure is necessary to ensure energy security, a sustainable industrial transformation needs to emphasize transformative solutions.

Internationally, market-based mechanisms such as the CBAM have an important role to play in preventing carbon leakage and providing incentives for emission reductions abroad. In addition, Germany and the EU need to look for new ways to incentivize industrial decarbonization with trading partners. Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) concluded with countries like India and South Africa could become blueprints for financing green industrial production abroad and reducing carbon leakage.