Faced with increasingly dangerous extreme weather events, the global community is more divided than ever on how to move forward on climate policy. Denial and support of dirty forms of energy production have become common themes of populist parties around the world. Crowds in Washington, DC, cheered on President Donald Trump, for example, as he signed the decree withdrawing the United States from the Paris Agreement – while their compatriots in California were displaced by raging wildfires. The vast majority of countries, however, vowed to stay on course. This was most recently signaled at the World Economic Forum in Davos, where companies doubled down on their commitments to become cleaner. The European Union (EU), which has a record for leading international climate action, will therefore be crucial for driving progress while the US government tries to obstruct international cooperation.

Internally, the European Green Deal set a legally binding goal to be net zero by 2050. The European Climate Law and Fit for 55 package delivered the midterm legal and regulatory means for achieving this. These measures were bolstered by the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) and the financial targets in European recovery finance and budgeting. These were all milestones of climate action, and von der Leyen’s reelection means this path is locked in. The internal ambition for climate protection provides strong positioning in climate diplomacy. The EU is a significant contributor to international climate finance and is using multiple instruments to build global momentum for emissions mitigation and resilience to climate impacts. Some of its internal climate policies also have external dimensions. It does not, however, have a formalized framework guiding its climate foreign policy. Also, the climate portfolio is currently distributed across multiple Commissioners. Hence, the EU could benefit from more coordination, especially as European institutions play a bigger role in aggregating and magnifying the climate action of member states. This DGAP Memo gives an overview of European climate foreign policy and identifies how certain elements of the EU climate agenda could be strengthened.

European Commission Advancing Climate Foreign Policy

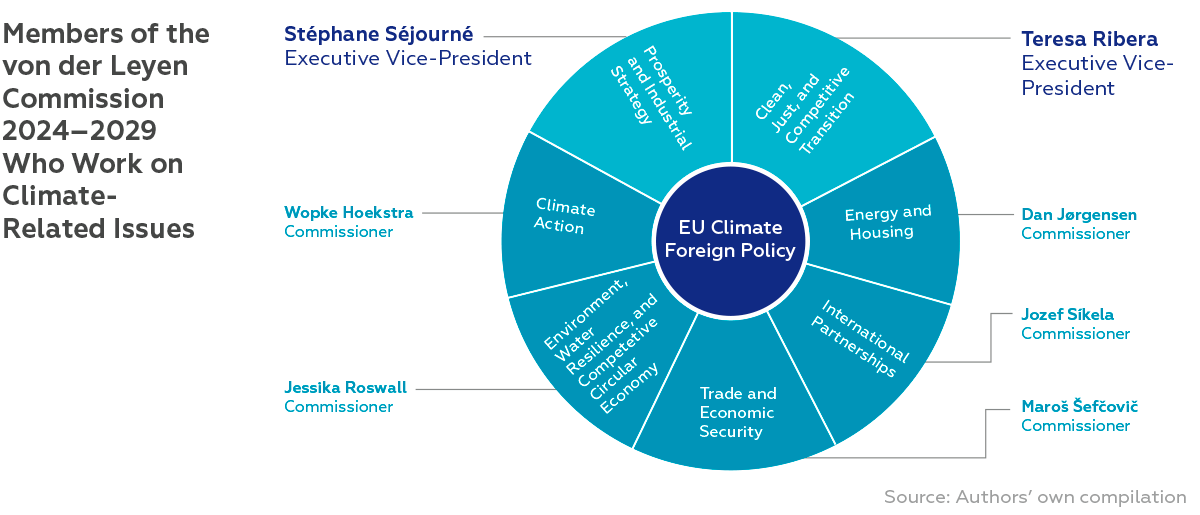

The previous Commission drove EU domestic and foreign climate policy. While the new Commission continues this path, it will focus more on the economy. Initiatives such as the Clean Industrial Deal, which is expected to be formally unveiled on February 26, 2025, show the deepening connection between competitiveness and the green transition. In the previous cycle, the strategic direction was centralized under First Executive Vice President Frans Timmermans who oversaw the Green Deal and Climate Action until 2023. The new Commission has divided this portfolio across several Commissioners, mainly tasking Teresa Ribera with Competition, Wopke Hoekstra with Climate Diplomacy, Dan Jørgensen with Energy, Jessika Roswall with Environment, Maroš Šefčovič with Trade, Jozef Síkela with International Partnerships, and Stéphane Séjourné with Industry. Diffusing climate foreign policy across multiple Commissioners can strengthen policy outcomes by allowing further specialization and mainstreaming into broader policy fields. However, without proper coordination, there is a risk of diluting the strategic direction previously afforded by a centralized figure.

Most policy expertise is centralized in the Commission’s Directorates-General (DGs). While DG Climate is the thematic lead, many DGs are involved in climate policy – for example, DGs for Energy or Transport at the sector level or DGs for International Partnerships and Enlargement at the governance level, which are central for projects outside of the EU. Demarking competencies across DGs can be challenging, especially for cross-cutting issues such as CBAM, which is spearheaded by the DG for Taxation and Customs Union As a result, staff have seen broader cooperation on climate issues among personnel across DGs. However, as exchanges occur at the working level, this coordination is neither always visible nor formally institutionalized.

The European External Action Service and the Role of EU Delegations

The European External Action Service (EEAS), another key actor, serves as the intermediary between member states, EU institutions, and delegations abroad. The EEAS plays a crucial role in chairing the Green Diplomacy Network (GDN) and coordinating climate diplomacy to help member states align their efforts toward a common agenda with clear goals ahead of the annual meetings of the Conference of the Parties (COP). The EEAS also hosts the EU’s Special Envoy for Climate and Environment, a position that research has shown can provide the EEAS with agency to initiate EU engagement in plurilateral initiatives.

European delegations implement climate foreign policy and intermediate between Brussels and the representatives of member states and the respective host countries. This mostly consists of communicating EU climate objectives, relaying local climate priorities, and coordinating climate expertise among member state representatives, sometimes achieved through localized GDNs. Familiarization with local positions can work well with targeted capacity building and project scoping. In such instances, the EU delegation can leverage technical cooperation with Commission staff to advise local actors on creating regulatory frameworks that comply with EU standards. When established, the delegation can then pivot to identifying a pipeline of projects ready for European investors.

If well managed, this can strengthen third country climate ambition and reinforce Brussels’ role in setting international climate standards. However, in practice, this does not always occur. Communication from Brussels is often rigid, technocratic, and highly focused on priority partners such as Brazil, China, and India. Research investigating EU diplomacy around the CBAM reiterates this, emphasizing that the EU had little discernable interest in accommodating the concerns of non-EU countries. While the implementation of the CBAM was not impeded by this, other legislation, such as the Deforestation Regulation, remains highly contested by major strategic partners like Brazil.

While better communication and a more open approach from Brussels could smooth this process, limited human and fiscal resources make it difficult. When input from some delegations is listened to or actively sought out while input from others is muted, tone-deaf communication can result. This occurs because Brussels-based actors, many of whom have never visited the host countries in question, are not always familiar with local counterparts or conditions. And this often remains true despite research showing that robust contact between delegations and DG Climate staff in Brussels leads to observable variations in a given delegation’s activities. In other words, it produces stronger climate outcomes.

Mainstreaming Climate Foreign Policy

The EU has proactively integrated climate in foreign policy; however, this positive step has been strained by geopolitical tensions. Russia’s war of aggression against Ukraine has undermined energy security, China’s technological consolidation has subverted industry, and the second Trump administration’s policy agenda will strain transatlantic relations. Such developments have caused a pivot to mainstream climate policy with competition, economic security, prosperity, and technological sovereignty. The Draghi and Letta Reports, as well as the new Commission portfolios, highlight this. The terms competitive, growth, and just, for example, are linked to climate and environment portfolios while prosperity is linked with industry.

Research shows that trained individuals are key for shaping European climate diplomacy. Even with climate broadly integrated, the quality of coverage can deteriorate if staff lack expertise and time. Staffers might have climate in their agenda, but it exists alongside other priorities. Consequently, despite having a lot of staff “working on climate,” these staffers may not be able to deliver all outcomes and climate may not receive meaningful coverage. Further, without the defined and measurable goals that a more explicit climate foreign policy strategy can provide, they may not even be working in the same direction.

Recommendations to Strengthen European Climate Foreign Policy

Adjust European climate and energy policy to articulate and operationalize European strategic interests. Europe needs to triangulate strategic interests for climate and formulate measurable and quantifiable policy goals that have integrated and utilized indicators – especially in public procurement and project finance. While some of this already exists, the weight of indicators is skewed toward lowest cost, which often misses European competitive advantages. For example, the public order of the Belgian transportation company De Lijn for 92 electric buses from the Chinese firm BYD was sensible on cost, despite BYD being outperformed on warranty and sustainability by European offers. Rebalancing criteria would allow finance to support European actors who offer other important outcomes – also such as the “security premium” that is currently not priced in. Doing so would help bridge the gap between Chinese and European offers. Nevertheless, strategic support should prioritize projects that are bankable and in which Europe is competitive (i.e., offshore wind). Any articulation of these interests should also aim to create space for the engagement of non-aligned actors such as Brazil or India.

Strengthen coordination among the member states, EEAS, and Commission to improve the efficiency and impact of existing climate action. Given limited resources, improving efficiencies is the best way to maximize outcomes. In climate action, coordination reduces duplicative efforts, often at little or no cost. For example, member states could sponsor joint diplomatic postings with a climate focus in key countries with limited representation. This could be achieved as simply as by having one staff member from a given DG or member state’s foreign office join weekly staff meetings or could go as far as funding colocations of staff working on climate from the EEAS and DG Climate and Energy within Brussels. Stronger coordination between the EU’s internal and external climate policies could help by expanding the GDN to also include more working-level staff across ministries in member states.

Leverage Europe’s climate record with clear and open communication. Ambitious targets and a credible track record position Europe as a legitimate climate leader. Major countries have responded to this, which has even caused them to strengthen their Nationally Determined Contributions. However, Brussels can be inward-looking and technocratic. Because European climate action has increasing implications outside of the EU, this presents challenges for productive cooperation – especially with partners like Brazil. The EU needs to simplify its communication and create more opportunities to integrate external input gained through delegations on the ground.

Continue to standardize an approach to using specific country initiatives to centralize and streamline climate action. The partnership structure of Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs) shows promise for broader climate action. They are built on high-level political legitimacy and local engagement, which allows the partner country to drive the exchange. At the same time, they serve as a central hub that “Team Europe,” the GDN, and Green Diplomacy Hubs can coordinate around. However, climate needs to be emphasized in conjunction with other mutually beneficial outcomes, such as improved economic security and diversification.

Methodological note: This memo builds upon expert interviews with ten EU officials, scientists, and civil society actors that were conducted with prior and informed consent. The interviews were held in English and transcribed.