This online text is the Executive Summary and introduction of the report. To view the full report and the footnotes, please download the PDF version here.

Executive Summary

Migrants increasingly have a say in migration policies. Diaspora and migrant associations rightfully step into the spotlight to bring their much-needed perspectives to policy development. But the work of associations of returned migrants has stayed in the shadows despite their having firsthand experiences that can guide the design of reintegration policies.

This study highlights such returnee networks around the world and proposes a typology to differentiate them along four lines, based on their creation (self-organized vs. engineered), structure (peer-to-peer vs. charitable), membership (forced vs. voluntary returns), and functioning (informal vs. formalized).

In some countries, returnee networks are numerous and widely known; in others, they are all but unheard of. One important factor for their creation is to have a large number of migrants return at the same time; another is the existence of role models of successful former returnees’ networks. But shared challenges also play a role, such as stigma and trauma, gaps in reintegration support, and the absence of family support systems, which make coming together with peers a more acute need. Support by external actors and an active civil society also help networks flourish.

Returnee networks hold great potential. They can provide practical support to recent returnees in matters such as housing, employment, and dealing with bureaucratic hurdles but also give psychological help and guidance. They can function as trusted intermediaries which inform new arrivals about available help and give valuable feedback to reintegration service providers. Crucially, they can be credible advocates for returnees’ interests toward their governments and educate their communities about the risks of irregular migration and the realities of migrants’ lives upon return.

But they also come with limitations and risks. Power struggles and elite capture are a risk, especially when networks serve as an income source for their founders. The lack of female representation is as common as it is lamentable. Like many grassroots initiatives, returnee networks often lack professionalization, which can lead to poor quality of work or the duplication of existing services. Even some of their positive functions can have downsides: When networks funnel other returnees toward existing services, this intermediary role risks increasing assistance shopping and chain support. When they engage in awareness-raising campaigns, there is a risk of re-traumatizing those who repeatedly tell their difficult stories. Lastly, networks may delay reintegration by solidifying the returnee status of their members rather than helping them move on.

Returnee networks are thus akin to a double-edged sword. Policymakers and practitioners in development agencies and other government units, international organizations, foundations, and civil society organizations who want to engage with returnee networks should consider the following recommendations to support returnee networks’ strengths and navigate their pitfalls:

1. Representation matters: Map and engage with returnee networks but beware self-proclaimed leaders’ ability to speak for returnees.

Not all returnees engage in networks, and some voices within networks are given more weight than others. Development actors should identify and map the returnee groups that already exist in their respective locations. They should look at who the leaders and members are and then engage with several of them to assess how representative a group is. As part of the mapping, development actors should develop criteria to measure the accountability and reliability of the networks and weigh the possibilities and limitations of engaging with them in their specific context.

2. Money matters (but is not everything): Consider financial support for accountable networks, and in-kind support for professionalization and cross-border exchanges.

Financial support for trustworthy networks with a system of checks and balances can be useful, especially when funding activities that the networks can do uniquely well. To newer and less formalized groups, development actors should provide in-kind support such as capacity building workshops to help them professionalize. They should also set up bilateral and group exchanges to connect networks across countries or regions. Development actors can also act as a bridge between networks and local government units, especially where trust toward authorities is low, to help establish working relationships that last beyond project cycles.

3. Timing matters: Decide whether you want to initiate new networks or partner with established groups.

Actors should carefully consider their goals and the trade-offs involved when deciding at which stage to engage with networks. While setting up new networks can help to pursue own goals, for example to send messages, engaging with established networks has the benefit of tapping into their strong connections to returnees. Since established networks may be hesitant to engage if they perceive that it puts their credibility at risk, cooperation must be built slowly and based on mutual interests.

4. Location matters: Engage with returnees not only in countries where European attention looms large but wherever numbers are high and conditions favorable.

European development actors should invest in reintegration in countries with high numbers of returnees, not just in the main countries of origin of migrants living in Europe. The presence of a critical number of returnees in a country makes it more likely that its government invests in reintegration infrastructure, which makes donor investments more sustainable. Also, investing in reintegration in those countries makes European countries’ engagement more credible as it involves less immediate self-interest.

5. Choice matters: Expand reintegration goals to include migration in the region and beyond.

The success of reintegration programs depends on the ability of returnees to live a decent life with choices and opportunities for the future. This requires investments in migration relationships that include legal migration pathways. Involving returnee networks in shaping those pathways can improve them since former migrants have firsthand experience of migratory aspirations, missing support systems, and practical obstacles of which policymakers may be less aware. Bringing the experiences of returnees into migration policy design is overdue – in reintegration programming and beyond.

Introduction

Return can be a normal part of the migratory cycle. Some forms of return are highly politicized, such as the forced return of rejected asylum seekers, but others, such as the voluntary return of students when their visas expire, tend to happen smoothly and beyond the public eye.

All returning migrants face challenges reintegrating into their countries of origin: They need to find a place to live, a job, a spot in a school, and a place in their community. Some find this easy, but for others, reintegration can take a long time. This is especially true when people return after many years abroad or against their will, be it through deportation or because they have lost their jobs or residence permits. Family demands can also mean that people return who would rather have stayed abroad.

European countries have become increasingly active in the field of reintegration in recent years, especially since the migration crisis of 2015. Reintegration assistance aims to support the sustainable return and reintegration of former migrants in their countries of origin. Yet such efforts face criticism and limitations: Short-term and individualized support cannot address root causes of migration and displacement such as poverty, insecurity, and lack of opportunities, which are factors that provoke outmigration in the first place. European actors are driven by their own political priorities, which can shift quickly, and may not fully consider the needs and priorities of returnees and communities in countries of origin. They can thus reinforce power imbalances and perpetuate a sense of dependency instead of empowering local actors and communities to take up and lead the reintegration process. This is compounded by the fact that partner governments are not always able or willing to build up national and local reintegration infrastructure in lockstep with donors’ investments to fill the gap when project cycles end.

More and more research focuses on ways to deal with these challenges, empower returnees’ voices, and foster reintegration to help returning migrants find a new footing in their countries of origin. But reintegration still is a comparatively young field of research. Much less is known about the reintegration of returning migrants than about the integration of those who settle in a host country. Research on migrants abroad, the so-called diaspora, goes back to the 1970s and provides a rich tapestry of knowledge, while research on migrants returning from abroad, the so-called returnees, only started gaining traction in the last decade and resembles a puzzle with many missing pieces.

One of these missing pieces are returnee networks. Recent studies suggest that returnees can play an important role in reintegration policies and that returnee-led reintegration projects may be more sustainable than government programs or other third-party projects because they tend to have greater credibility and ties within migrants’ and origin communities. But despite the potential benefits of these networks, we know little about them.

This study aims to fill this gap. It provides practical recommendations for policymakers and practitioners on how to engage with returnee networks and how to navigate their pitfalls. To this end, it answers four sets of questions:

- What are returnee networks, how do they vary, and in which countries and regions are they located? (Chapter 2)

- Which factors enable the creation of returnee networks? What conditions are conducive to the flourishing of such networks? (Chapter 3)

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of returnee networks? What potential and opportunities do they bring, but also what limitations do they have and what risks can they carry? (Chapter 4)

- When and how should development actors engage returnee networks, and when explicitly not? How should reintegration programs change to become more equitable and sustainable? (Chapter 5)

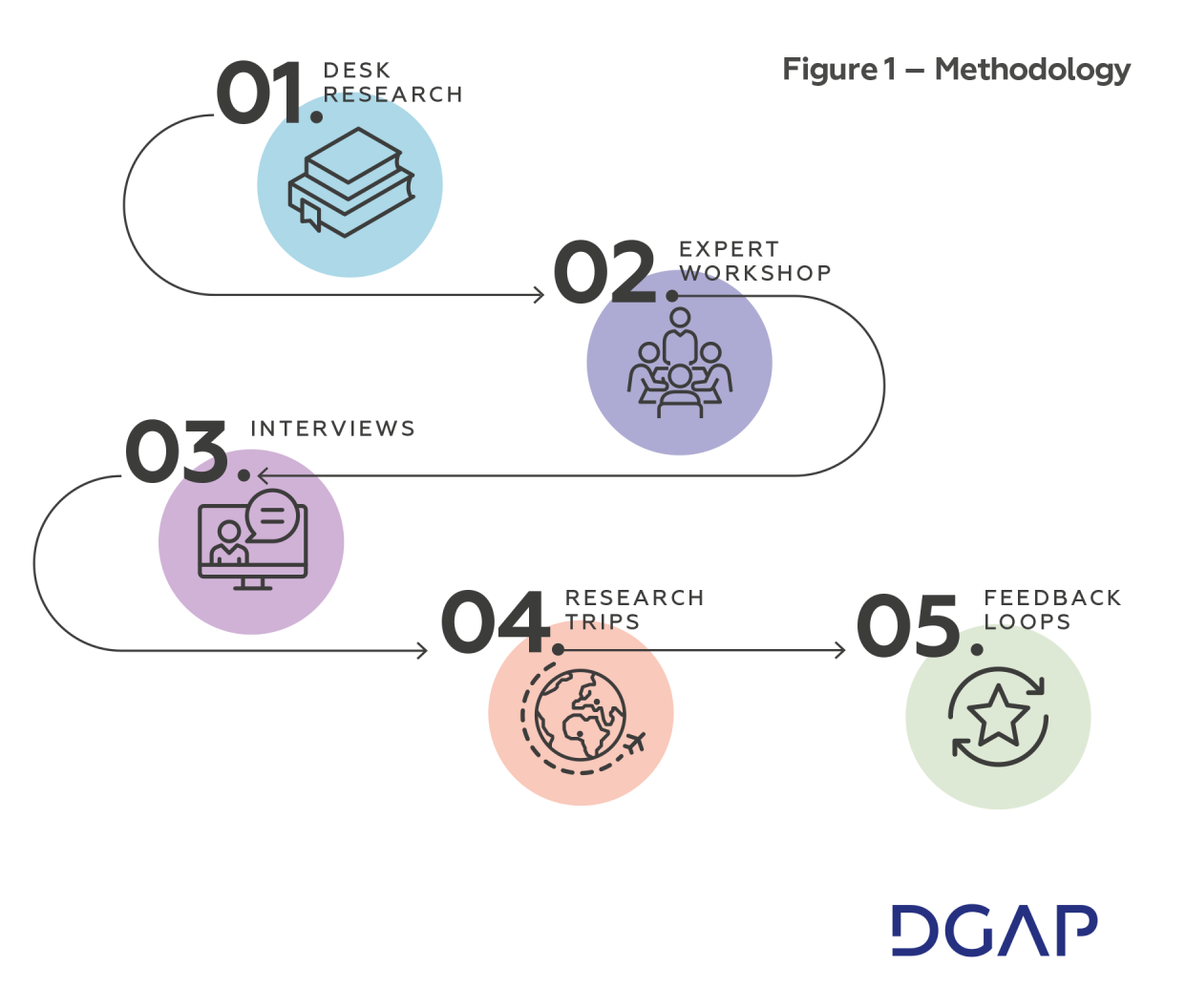

The researchers addressed these questions in five steps. They conducted (1) extensive desk research and a review of relevant literature, with a focus on recent literature since 2015; (2) a closed-door expert workshop in the summer of 2022, which brought together academics and practitioners to take stock of the state of knowledge and experience with returnee networks; (3) 54 virtual and in-person interviews (held via video platforms and following a semi-structured interview guide) with founders and members of returnee networks as well as with reintegration experts in twelve countries; (4) two research trips to countries with large-scale return migration: Nigeria (Lagos, Abuja, and Benin City in August 2022), where returnee networks are common, and Kosovo (Pristina, Fushe Kosova, and Mitrovica in November 2022), where they are rare. For a deep dive into two different country contexts, the researchers set up five focus groups with a total of 40 returnees and conducted an additional 47 in-person interviews and site visits with representatives of returnee networks, government units, international organizations, civil society organizations, academia, and the private sector. The final step (5) consisted of feedback loops with thirteen external experts and three briefings with more than 50 reintegration practitioners to put the findings and recommendations through a reality check before publication. Further information, including the concept note of the workshop and lists of the virtual and in-person interviews, is available in the annex.

The results of this study come with five limitations. First, the researchers identified returnee networks and relevant experts via a snowball system. As their entry point, they used organizational contacts, authors, and institutions chosen on the basis of their literature research as well as contacts named by the project’s supporters, namely Germany’s development agency “Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit” (GIZ). From then on, they worked through referrals. It therefore is likely that the choice of interviewees carried a bias toward more established persons and organizations and toward GIZ’s partners. This is especially the case for the participants of the focus group discussions in Nigeria and Kosovo, most of who were prior or current GIZ beneficiaries.

Second, the findings of the study are shaped by the country case studies of Nigeria and Kosovo. Although the desk research and interviews yielded information about returnee networks in many countries, the findings and recommendations are strongly influenced by the reintegration conditions in both countries and the impressions the researchers gathered during their trips. The findings may thus be less easily adaptable to contexts outside of Western Africa and the Western Balkans.

Third, the research trips came with time and resource constraints. The researchers spent 17 days in Nigeria and seven in Kosovo. In Nigeria, security constraints limited the locations researchers could access as well as their ability to move freely and spontaneously between locations.

Fourth, language barriers may have affected the results. The researchers conducted the interviews in English, German, and French, which may have hampered the inputs of interviewees who are non-native speakers of these languages. Also, the linguistic barrier during the research trip to Kosovo meant that many conversations were filtered through an Albanian-to-English translation.

Fifth, and perhaps most importantly, this research, as so much research on return and reintegration that has been done over the last years, reflects European political priorities and interests that have, inadvertently but undoubtedly, turned the topic of return migration into a market. This study is inevitably part of this market. The researchers are Germans who conducted a study funded by a German donor with the explicit goal of developing recommendations for future projects in the realm of German and European development cooperation. These facts may have influenced interviewees’ answers and discouraged some from expressing strong criticism. The results and recommendations do attempt to shed light on the activities and perceptions of returnees as protagonists of reintegration, but they are filtered through a German lens. This study therefore does not formulate local solutions for returnee networks but for German and European policymakers and other actors pursuing development goals.

The Basics: Return Migration, Reintegration, and Returnees Explained

- Return migration

-

is the overarching term for the process of departure of migrants from a host country to their country of origin, home country, or to a country crossed on the way to the host country. Return migration can take place voluntarily (without state coercion) or forcibly (with state coercion), with or without financial support from states, and independently or organized by state agencies.

- Reintegration

-

is the process of re-inclusion or re-incorporation of migrants following their return into their country of origin. There is no universally agreed definition of reintegration, but existing research often divides the process of reintegration along three dimensions: economic reintegration, leading to financial stability and self-sufficiency; social reintegration, such as access to adequate social services including health and education; and psychosocial reintegration. Other dimensions like legal, cultural, religious, or linguistic reintegration as well as physical and emotional safety and security are sometimes grouped as part of these three dimensions and sometimes treated as additional dimensions.

- Returnees

-

are persons who have migrated abroad and returned to their country of origin. This report uses the terms “returnee” and “return/returned/returning migrant” interchangeably, but the term returnee carries different meanings in different countries. For instance, in Nigeria, a “returnee” is a person who has returned using a return program. In contrast, in Kosovo, the term “returnee” describes a person who fled the region during the Yugoslav Wars and now returns, while a person who arrives back in Kosovo because he or she does not have of legal basis for staying in a foreign country is labeled a “repatriated person.” This contrasts with the terminology of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) which explicitly defines “repatriation” as the return of refugees. These nuances matter because they determine the reintegration aid returning persons can access – or are excluded from.

This online text is the Executive Summary and introduction of the report. To view the full report and the footnotes, please download the PDF version here.