| The scientific evidence on the link between climate impacts and migration has increased considerably in recent years, but development and foreign policy measures are lagging behind the state of knowledge. |

|

|

|

Please note the online version of this policy brief doesn't contain footnotes. To view the footnotes, please download the PDF version here.

Germany’s Climate Foreign Policy Strategy: Responses to Migration Are Indispensable

Migration, displacement, and resettlement due to climate change are not distant future scenarios but are now materializing along increasingly severe extreme events and gradual degradation. In view of advancing global warming and the danger of crossing tipping points in the Earth system, forward-looking climate foreign policy and development policy should increasingly focus on severe climate impacts. This is because the importance of climate protection, adaptation, and the prevention and handling of climate-related crises will increase in the coming years – all scenarios of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), with their best estimates for temperature development in the near future, assume further warming to at least 1.5°C above the pre-industrial level by 2040. The accompanying shifts in climate zones will inevitably impact population distribution. Higher degrees of warming could far exceed the limits of adaptation.

This results in an acute need for action in German climate, domestic, and foreign policy. Germany has a strategic interest in raising the profile of climate migration and forging alliances to support internally displaced persons so that humanitarian emergencies do not escalate into security crises.

The publication of the German government’s Climate Foreign Policy Strategy (Klimaaußenpolitik-Strategie (KAPS)), planned for the first half of 2023, offers an opportunity to develop comprehensive solutions for the main fields of action in climate policy. The scope of climate migration extends far beyond traditional departmental boundaries and the KAPS offers the opportunity to define approaches common to all departments. The issue must be considered holistically across the entire migration cycle – from preventing forced migration through agricultural adaptation to enabling migration to protect life. The year 2023 will see the adoption of other landmark documents that are also important. For example, the Guidelines for a Feminist Development and Foreign Policy were published in March and broaden the view for a comprehensive, intersectional understanding of human security, as well as the National Security Strategy, which is in reconciliation among the departments.

International climate diplomacy is also increasingly focusing on climate migration, for example through the fund for financing climate-related damage and loss agreed at the climate change negotiations in Sharm El Sheikh in 2022. The design of the fund is currently being discussed by a transitional committee of which Germany is also part. The creation of the fund also identifies displacement, resettlement, and migration as gaps in the financing system. The growing importance of climate migration was reflected at COP 27 in the first pavilion on human mobility (“Climate Mobility Pavilion”). International organizations such as the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM) are increasingly addressing the issue, as are countries such as the United States, which published the White House Report on the Impact of Climate Change on Migration in 2021.

Climate Crisis and Displacement Will Become the Task of the Century

Climate-induced mobility is already a reality. Especially at higher levels of warming, which are becoming increasingly likely given sluggish measures to reduce emissions, larger areas – some of which are densely populated today – would inevitably become uninhabitable.

However, different terminology and definitions of climate migration lead to different measurements and predictions of future migration patterns. This limits their comparability but, at the same time, makes it possible to look at different dynamics. The robustness of many predictions is constrained by the limited availability of migration research data and in climate impact research in particularly exposed regions with large vulnerable populations. Likewise, many researchers are faced with the question of when people facing major crises should migrate and when they should stay. This multi-layered consideration has not only economic dimensions, but also relates to cultural, family factors and other aspects of place attachment such as place-specific economic activities.

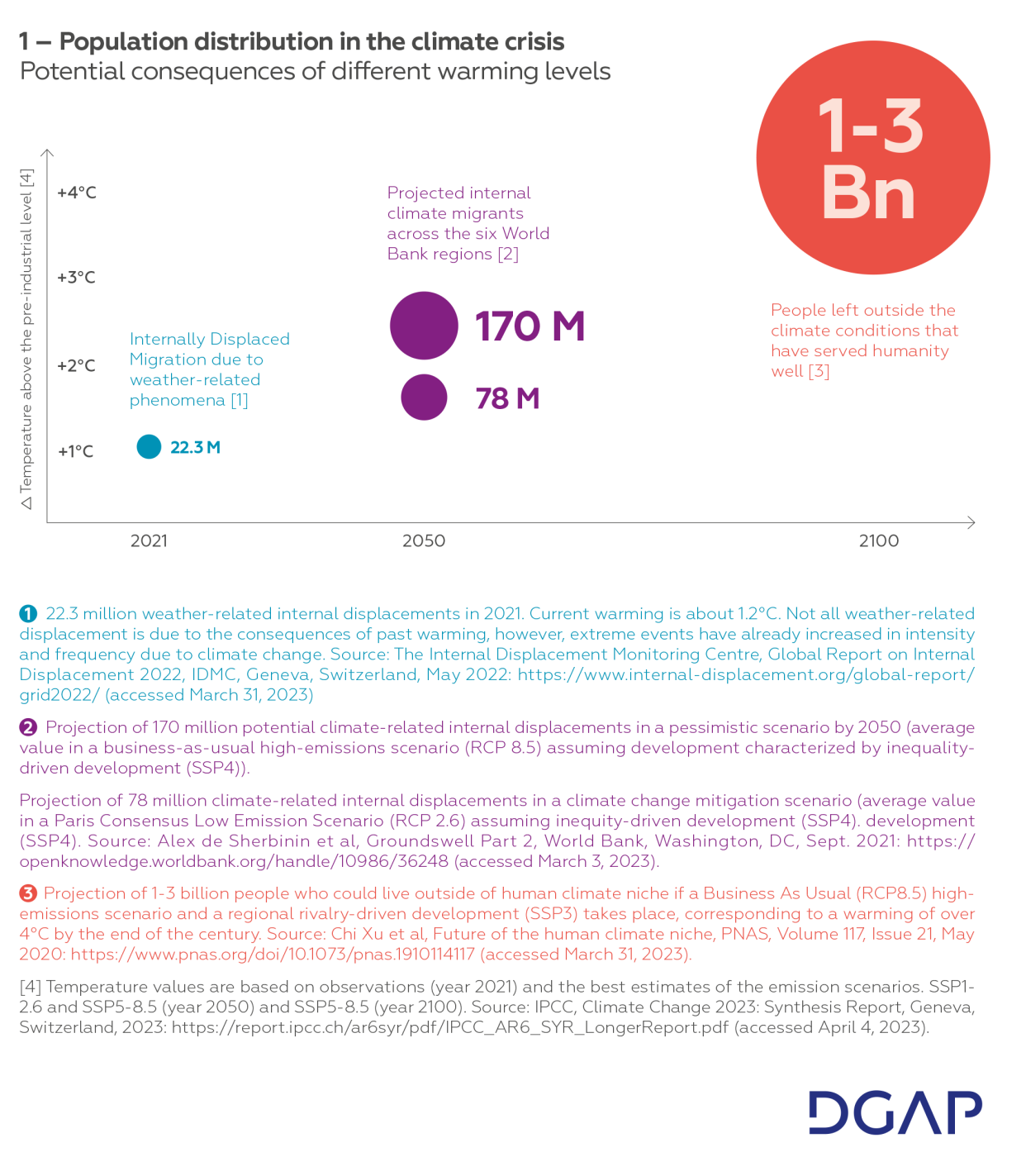

In 2021 alone, there were 22.3 million new internal displacements due to weather-related natural disasters. While these are not largely attributable to past anthropogenic warming, climate science indicates that these types of extreme events will increase in frequency and intensity. The population in affected areas is also growing.

Assuming a pessimistic scenario in the Groundswell Report, the World Bank projects an additional internal migration of 170 million people in six world regions due to slow climate change already by mid-century (see Figure 1). In this scenario, high emissions would continue and uneven development would take place. In an ambitious climate change scenario, this number could more than halve to about 78 million displaced people by 2050. The assumptions are even more serious in a high emissions scenario by the end of the century. According to this scenario, by 2100, one to three billion people could live outside the human climate range, i.e., the temperature corridor of 11 to 15°C annual mean temperature that favored human development. While currently only 0.8 percent of the Earth’s land area has an annual mean temperature above 29°C, in the future one third of humanity could live below these extremes, which are currently present in parts of the Sahara, for example. It is difficult to imagine that these extreme climatic conditions would allow such large populations to be fed, even with progressive development, especially since many countries that are currently characterized by great poverty would be affected. Large migration movements without precedent and humanitarian emergencies would be the result.

Even if, according to current knowledge, most climate-induced migration will take place within countries if climate protection is ambitious, it is likely that the urge for cross-border migration will also increase. This will also be influenced by recurring extreme events that erode resilience in places of refuge in the affected countries. Especially in countries like the Small Island States, whose entire territory is threatened by climate impacts, migration could be the last resort to protect people. Nevertheless, many people do not want to leave their homes. A survey on the African continent indicates that the majority of the population already affected by climate change does not want to migrate. Climate impacts can also limit the possibility of migration because the financial prerequisites for mobility disappear due to a loss of prosperity. In this respect, it is difficult to predict when climate extremes will lead to migration and when they will lead to a local humanitarian crisis.

Reception of Climate Migration in the IPCC and COP Process

Scientific findings on climate-induced migration were already taken up in the IPCC in the 1990s and recognized as potentially the most serious effect of climate change. However, integrating the issue into the COP process was slow (see Figure 2). It was not until 2010 that it was formally integrated into the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change through the Cancún Adaptation Framework (COP16).

The scientific evolution in the IPCC, which increasingly identified migration not only as a consequence of the climate crisis but also as a form of adaptation, laid the conceptual foundation distinguishing among migration, displacement, and planned resettlement at COP16. This illustrated the growing awareness of the complexity of climate migration as reflected in the 4th IPCC Assessment Report. At COP19 in 2013, the Warsaw Mechanism on Loss and Damage was established, which included a “human mobility” work stream. Under this mechanism, a Task Force on Displacement was established at COP21 in 2015. Displacement dynamics were thus understood as climate-related damage and loss. In the COP27 Cover Decision, the Sharm El Sheikh Implementation Plan, human mobility was named for the first time beyond the preamble in the newly introduced section on damage and loss. The impact of this link could be reflected in the further negotiations on the Damage and Loss Fund, in which, for example, more funds will be made available for climate displaced persons in the future.

Displacement in the Context of Climate Change Falls Through the Cracks of International Law

The central international treaties for the international protection of refugees – the Geneva Refugee Convention (1951) and its Additional Protocol (1967) – date back to a time before scientific research on climate change. These two international treaties still regulate the rights and protection of refugees today – linked to the definition of a “refugee” as defined in Article 1 (2) of the Refugee Convention. The understanding of refugees under international law is, therefore, essentially shaped by the persecutions and displacement dynamics of the Second World War and the fascist dictatorships in Europe.

A “refugee” is therefore a person who, firstly, is outside the state in which he or she has his or her regular place of residence and, secondly, is unwilling or unable to return to that state due to a well-founded fear of persecution. The Refugee Convention only recognizes “race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or (...) political opinion” as grounds for persecution. In the case of climate-induced migration, the second condition is often not directly fulfilled so that climate refugees are generally not considered as refugees in international law and are usually denied adequate protection and possibilities to migrate legally.

The principle of non-refoulement under international law prohibits the refoulement of refugees to states or regions where they are at risk of serious human rights violations due to persecution. So far, national and international courts have not applied this principle to climate refugees. However, this may soon change: The UN Human Rights Committee, in its first ruling on a case of a person fleeing climate impacts from Kiribati to New Zealand, stated that a refoulement would be unlawful in the future if climate impacts threatened the climate refugee’s right to life in the home country.

International Protection of Climate Displaced Persons – A Soft Law Patchwork

In 2016, the UN General Assembly explicitly recognized the link between climate impacts and migration for the first time in the New York Declaration. In a two-year process, two frameworks were then developed to increase the protection of refugees: The Global Compact on Refugees (GCR) and the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration (GCM).

The GCM, in particular, offers approaches to legally improve the situation of climate refugees. Its 23 non-binding frameworks aim to facilitate safe and orderly migration. In objective 5(h), states advocate for improving the availability and flexibility of pathways for regular migration, explicitly including climate-related migration. As the frameworks are not legally binding, they rather serve as signposts on how states should regulate safe and equitable migration.

The definition of internally displaced persons in the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement also includes people who have fled due to natural disasters or climate impacts. However, this document, published in 1998, is merely non-binding soft law, which has so far only been implemented in a binding manner by the member states of the African Union (AU) in the Kampala Convention. Legally, it would easily be possible to create legal and safe escape routes on this basis, but the political will has been lacking so far. The EU recently proved for Ukrainian refugees that a temporary protection regime is quickly possible. On March 4, 2022, the protection mechanism provided for in the so-called EU Temporary Protection Directive (EU-TPD) since 2001 was activated for the first time with the help of the necessary unanimous decision of the European Council. On this basis, affected persons could immediately and collectively – i.e., without lengthy individual procedures – seek temporary protection from Ukraine in the EU member states. The same procedure was recently discussed for those affected by the devastating earthquakes in Turkey and Syria. A decision for those affected by geophysical natural disasters could lead the way for weather-related extremes.

The Perspective of Feminist Foreign Policy

Feminist perspectives call for a shift in perspective that considers human security intersectionally and takes climate justice into account. This is because displacement due to climate change is a consequence of the overexploitation of natural resources predominantly in industrialized countries in favor of often non-marginalized, partly white people, which is particularly detrimental to BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) in developing countries.

The feminist foreign and development policy pursued by the German government thus has consequences for dealing with climate-induced migration. Political decision-making processes should therefore consider the needs of vulnerable groups particularly affected by climate change. With the initiative of the “Global Shield,” the global protective umbrella against climate risks, the German government has made an important advance that needs further development. An intersectional understanding of human security requires that in project planning and implementation, people who are marginalized, such as people with physical disabilities, children, LGBTQI+ people, women, and especially people who experience multiple discrimination, are consulted in particular.

Definitions

- Climate migration:

-

The movement of a person or groups of persons who, predominantly for reasons of sudden or progressive change in the environment due to climate change, are obliged to leave their habitual place of residence, or choose to do so, either temporarily or permanently, within a state or across an international border.

- Disaster displacement:

-

The movement of persons who have been forced or obliged to leave their homes or places of habitual residence as a result of a disaster or in order to avoid the impact of an immediate and foreseeable natural hazard.

- Human mobility:

-

A generic term covering all the different forms of movements of persons.

- Planned relocation:

-

Planned relocation in the context of disasters or environmental degradation, including when due to the effects of climate change, is a planned process in which persons or groups of persons move or are assisted to move away from their homes or place of temporary residence, are settled in a new location, and provided with the conditions for rebuilding their lives.

- Trapped populations:

-

Populations who do not migrate, yet are situated in areas under threat, […] at risk of becoming “trapped” or having to stay behind, where they will be more vulnerable to environmental shocks and impoverishment.

Source: International Organization for Migration (IOM), Institutional Strategy on Migration, Environment and Climate Change 2021–2030. For a comprehensive, evidence and rights-based approach to migration in the context of environmental degradation, climate change, and disasters, for the benefit of migrants and societies, Geneva, October 2021: https://environmentalmigration.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl1411/files/d… (accessed April 12, 2023).

Recommendations for German Climate Foreign Policy

In summary, it is crucial to strengthen the protection of climate refugees and improve their situation legally. Policymakers and practitioners should muster the political will, both at the international level and within the EU, to create safe and just migration regimes. An intersectional understanding of human security should be at the forefront to focus on the needs of marginalized groups and thus ensure an inclusive and equitable approach in addressing climate-induced migration. The following recommendations are for implementation.

1. Use different funding instruments and target them at vulnerable groups

The German government should work to close the growing global financing gap for adaptation measures to the growing impacts of climate change. In addition to options on the ground, human mobility in the context of climate change should also be understood and supported as an adaptation strategy. This should also be considered within the framework of the “Global Shield,” for example through flexible insurance solutions for people who can no longer remain in the affected areas. Initiatives such as the Platform on Disaster Displacement, the Global Centre for Climate Mobility, and the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre can contribute important expertise on good practices and standards to develop appropriate program lines.

Funding for adaptation in cities at the interface of climate and migration is limited and should be scaled up. A large proportion of the world’s internally displaced already live in cities. Migration in the context of climate change will contribute to population growth in many cities in the least developed countries. Mechanisms to respond to the specific needs of cities and their vulnerable populations, such as the City Climate Finance Gap Fund supported by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), or the Mayors Migration Council’s Global Cities Fund on Inclusive Climate Action, should therefore be expanded.

Where the limits of adaptation are reached, support is needed for the vulnerable population in planned resettlement or migration. Knowledge about the risks and consequences of climate change should be promoted and made accessible to those affected so that they can make informed adaptation decisions. Early planned resettlement can reduce damage and losses. There is a need for an interplay of different financing mechanisms – from humanitarian aid to trust funds for individual regions or countries to bonds or special drawing rights at the International Monetary Fund (IMF) – to support countries and affected people in addressing the damage and losses they have suffered.

2. Thinking about climate and labor migration together

Labor migration should be facilitated as a pragmatic step toward regular, safe, and orderly migration pathways for people particularly affected by climate change. A labor training and mobility component could also be included in the emerging Just Energy Transition Partnerships.

Foreign climate policy as a cross-departmental task should therefore also include the foreign policy dimension of migration policy, which the new Special Representative of the Federal Government for Migration can advance.

Closing existing protection gaps and improving data

In the short term:

Grant temporary protection through humanitarian visas.

- The German government should offer unbureaucratic evacuation options and humanitarian visas on a quota basis to those who must leave their current place of residence at short notice due to climate change-related natural disasters or climate impacts.

- Within the EU, the German government should advocate to improve the protection mechanism of the EU TPD and work toward a low-threshold procedure rather than a unanimous decision of the European Council to activate the protection mechanism.

In the medium term:

Use multilateral forums, strive for migration partnerships, and improve the data basis.

- The German government should work to strengthen the Nansen Agenda. The Platform on Disaster Displacement should be tasked by its Steering Committee with an implementation report on the Nansen Protection Agenda of 2015. By 2025, the status of implementation measures to date should be analyzed and, if necessary, further recommendations for action should be formulated, including, for example, addressing internal displacement in the context of climate change.

- More operational cooperation and coordination at the regional level is needed. The regional “Africa Climate Mobility Initiative,” “Greater Caribbean Climate Mobility Initiative,” and “Rising Nations Initiative” contribute to filling this gap. Multi-stakeholder partnerships allow a common strategic direction of activities and priorities for funding at the regional level when functions and activities are dispersed between institutions. This should be based on both scientific evidence and civil society perspectives.

- Systematically improve data on climate migration. Since data collection is handled differently in different countries, comparative and summary studies are difficult. Data collection and analysis should be more harmonized through international standards. The International Forum on Migration Statistics or the Berlin-based Global Data Institute of the IOM could be used to develop guidelines for collecting data on climate migration to strengthen data infrastructures in the long term and thus lay the foundations for improved cooperation in this thematic area.

In the long term:

Commitment to safe and legal migration routes – within states and across state borders.

In the long term, the German government should work on the basis of the Nansen Agenda for a claim to protection under international law for climate displaced persons within states and beyond state borders. The GCM, with its International Migration Review Forum, provides an opportunity to discuss and track global progress in enabling regular migration pathways, especially climate-induced migration. Germany should advocate for the implementation of the Nansen Agenda here and in other forums, such as the Global Refugee Forum or the Khartoum Process. This will create the opportunity to discuss and track progress in opening regular migration pathways, especially also in climate-induced migration.