Goal: A Global, Integrated Grand Strategy for Germany

Germany requires a grand strategy in which economic and security policies work together, coordinating approaches to Russia, China, and transatlantic and Indo-Pacific relations under one framework. Internal strife divides Germany’s political parties, and its foreign policy is narrowly focused on Ukraine and Europe. This is understandable given Germany’s geopolitical position and explains initiatives like the Operations Plan Germany; however, the Russia-China-North Korea nexus shows these challenges are linked. As US leadership becomes uncertain, Germany needs a global vision beyond transatlantic ties. Policymakers must unite existing strategies into one framework that recognizes our interconnected world. This requires capacity building across government, the private sector, universities, and think tanks to expand talent and strengthen institutions.

Initial Situation: Germany Lacks a Strategy to Address Geopolitical Risks

Covid-19 and the US-China rivalry shifted focus from open markets to economic security and de-risking. Trade is now inseparable from security, just as climate change is linked to energy and migration. The G7 nations, a group of like-minded countries, agreed to coordinate on economic security related to supply chains, critical infrastructure, responding to economic coercion and non-market practices, and protecting the digital sphere as well as emerging and critical technologies.

Germany requires a grand strategy – a vision and an overarching strategy under which all other policies, current and future, fall

Technology is one example of how trade and economic security are increasingly interlinked. Yet, technological development comes with the development of both physical infrastructure (material connectivity) and ideational connectivity, with the latter being shaped by the values, principles, and ideas behind it. The varied interpretations of “digital sovereignty” are a case in point. Technology is a commodity, service, and means – inextricably linked to critical minerals, connectivity, trade, and hybrid warfare. These horizontal issue linkages and the interconnectedness between the material and ideational need to be reflected in policy.

Several countries, including the United States, China, and others, have already adapted to this new environment and its challenges. China, for example, has used digital connectivity to bring the Global South under its spheres of influence. In contrast, the United States has used technology and its norms to try to divide the world into the democratic and authoritarian camps. Germany now needs to decide which path it is taking. A grand strategy will allow the country to define its approach.

China has embraced connectivity – both material and ideational – with policies such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which are echoed by Russia in their Eurasian Economic Union. These initiatives target not only the terrestrial realm but also cyber (Digital Silk Road) and space (BRI Space Information Corridor). At the ideational level, these initiatives extend to climate change (Green Belt and Road) and development (Global Development Initiative) and have been written into the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations.

Compared to China, Germany is late to the so-called connectivity game – finding ports like Hamburg and critical sectors like robotics (Kuka) coming into China’s spheres of influence and only recently waking up to the need to reform its aid policies. Yet, despite its articulation of a “China strategy,” Germany’s response to Huawei’s role in the country’s network is puzzling and underwhelming. The response was delayed, valuable time was lost creating more technological complications than necessary, and there was much discussion in the media. In contrast, Japan responded to Huawei quietly and swiftly, allowing China to “save face” and avoid further tension. Japan’s case shows that when government, industry, and experts work together, the outcome is likely to be better.

Without a global perspective, Germany misses out on opportunities, particularly in the Global South. While China has an ambitious global vision embodied in the BRI, Global Security Initiative, and Global Development Initiative, Germany is far from being a global player. The expansion of both the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and BRICS (originally comprised of Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa) show that these groups and ideologies have reach beyond Eurasia and especially in the Global South. Another example is space; technological prowess and generous South-South cooperation make the space station led by China and Russia a more attractive option than the one led by the United States. Meanwhile, Germany’s space industry remains in the shadow of the US. Unless Germany can change this, the country will lose out in the connectivity game.

Next Steps: Going Global – Integrated Review and Institutional Change

Germany requires a grand strategy – a vision and an overarching strategy under which all other policies, current and future, fall – to make sure all sections of government and the private sector are working together toward one aim. Such a strategy would allow Germany to better represent its interests and reassert itself and not merely follow the lead of the United States. It is already apparent that piecemeal fixes cannot bring the results that a grand strategy promises. Despite Germany having recently placed an Embassy in Fiji or held discussions about establishing a military presence in the Indo-Pacific, for example, it still cannot compete with China who already has a policing agreement with Fiji and a security agreement with the Solomon Islands.

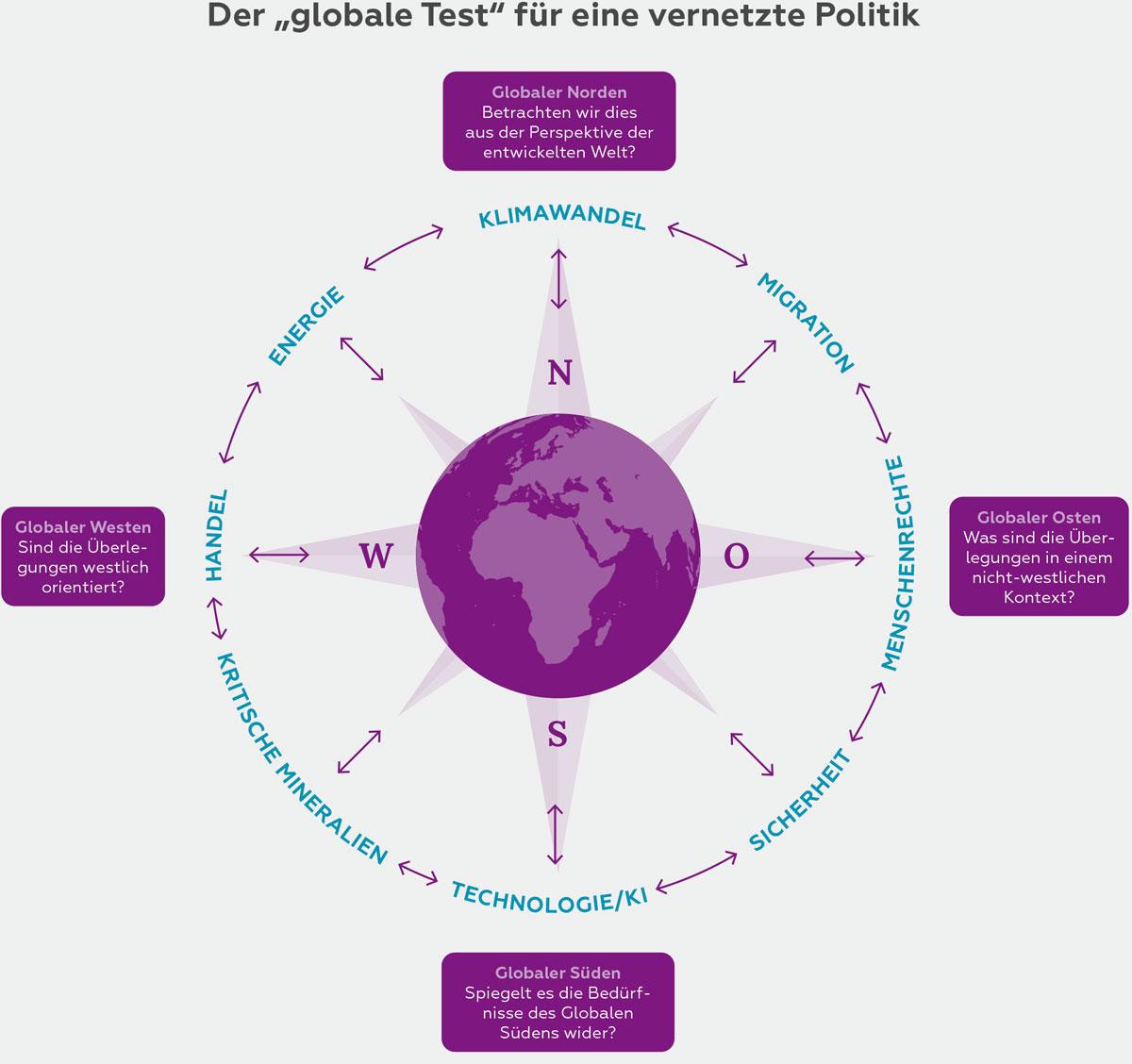

An effective grand strategy should not only consider what is important for Germany but also balance this with the needs of the Global South. Germany must also consider whether it has an inherent bias toward looking at things from a Western, European perspective. Because the world is interconnected, Germany should develop a grand strategy with a global perspective based on these primary steps:

1. Conduct an Integrated Review

Germany could learn from the examples of the United Kingdom’s Integrated Review 2021 and Integrated Review Refresh 2023. While far from perfect, they lay out the first steps for the UK to move away from an interdependent trade relationship with China and Russia.

A German integrated review will involve many iterations, formulations, and revisions, all of which should strive to:

- Address interregional issues that link Europe to the transatlantic space and Indo-Pacific, taking into consideration how Germany can promote its interests in balance with the Global South, North, East, and West;

- Develop capacity building for cross-regional expertise, emphasizing the horizontal issue linkages in policy; and

- Consider linkages between security and economics.

The mere existence of a Strategy on China (2023) and Guidelines for the Indo-Pacific (2020), which are not well coordinated with Germany’s National Security Policy (2023) and National Security and Defense Industry Strategy (2024) is insufficient. An integrated review should address trade and security in tandem. It must take on the challenges posed by China and Russia in a comprehensive – not piecemeal – manner. The review should not only involve representatives from across the German government but also bring in expertise from outside it, utilizing the rich debates taking place in industry, universities, and think tanks. This collaborative approach could then result in a blueprint for Germany’s grand strategy.

2. Widen Talent Pools and Capacity Building

Creating a grand strategy will require capacity building to ensure that relevant departments work together and have the expertise to address the key issues outlined above. A capability program that targets the knowledge gaps in the policy community, drawing on talent from academia and the private sector, may be useful. The term “revolving door” is often used in the Anglo-American context. As it suggests, the United Kingdom and United States have a diverse pool of talent in policymaking in terms of both disciplinary background and nationality – something that explains the rich policy debates in these countries and perhaps something Germany could consider establishing.

3. Expand Perspectives to Support a Grand Strategy

Germany’s government and industry currently lack the cohesion necessary for implementing a grand strategy. The country’s security policy is also predominantly situated within the European context. A shift from a European mindset to one that is more global is imperative. Institutionalizing a National Security Council (as in the United States and UK) or a geoeconomics council (as in Japan) may help in this regard.

4. Leverage the Positive and Yet Untapped Aspects of German Society

Germany has a long history of cultural exchange with India that goes back to the mid-19th century (and from which the historical baggage that other countries like the UK have is absent). Indeed, Germany currently attracts students and workers from all over the world. Yet, its policy circles and talent pool remain very domestic. Such ties put Germany in a leading position to be the connector of the transatlantic and Indo-Pacific regions, starting first with India.