| Tracking shows that multilateral action has made progress in decarbonizing the power sector. The initiatives that surpass targets should inspire greater ambition. |

| Inadequate metrics and data create gaps in awareness of efforts to act on commitments. Governments need to provide regular progress updates to secretariats and integrate more comprehensive data in their indicators. |

| Secretariats are crucial for supporting initiatives. Lack of consistent government support affects their ability to manage and report on commitments. |

| Despite India’s strong engagement, the absence of non-Western G20 countries participating in these initiatives is concerning because their power demand and emissions are rising. |

| Policymakers must mainstream best practices. Germany in particular could use this knowledge to build a cohesive Climate Club around common targets. |

The online version of this Policy Brief does not contain footnotes. To view the footnotes, please download the pdf version here.

Introduction

Although the climate crisis has become a priority in international politics, varying degrees of ambition has made it hard for states to find consensus in climate negotiations. Raising the ambition among smaller groups of states can augment the work of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) where negotiations are often slow and characterized by lowest-common-denominator compromises. This has led to a network of multilateral initiatives that cover many topical issues that are intended to complement the COP process.

Yet, it is not always clear how these initiatives contribute to accelerating the progress of the UNFCCC. Uncertainty stems partly from their varying aims, structure, and funding, as well as means of monitoring, which makes it difficult to track commitments. Such gaps undermine efforts to decarbonize because they reduce the ability to identify what works, where processes lag, and where to raise ambition. In 2020, the Future of Climate Collaboration project created an initial map of where and how actors engage in multilateral climate initiatives. This exercise elucidated, among other things, how the absence of a strong unifying narrative among initiatives can lead to overlapping efforts or gaps in coverage.

This brief advances these findings with a deeper assessment of voluntarily concluded inter-governmental initiatives that cover the power sector. It builds on the most up-to-date data offered by the Itad to consider geopolitical trends across these initiatives.

- The Importance of the Power Sector

-

The power sector is central to every net-zero trajectory. It is the world’s single largest emitter accounting for 14.65 gigatons of anthropogenic CO2 emissions in 2022, and thus responsible for roughly 40 percent of global energy-related emissions. A clean power system is also a prerequisite for decarbonizing other segments – from electric vehicles to green hydrogen – and the easiest sector in which to make significant emissions reductions. Since most power emissions stem from coal, directly replacing it with lower-cost renewables slashes emissions and saves money: the levelized cost of electricity for 86 percent of the new renewable capacity installed in 2022 was cheaper than its fossil-fired counterparts.

But the global power sector’s decarbonization is stalling. Even though the COVID pandemic slowed economies in 2020, the sector’s emissions grew by four percent from 2019 to 2022. Also, recent political crises, such as Russia’s war on Ukraine, illustrates how progress can be reversed: in 2022 the emissions intensity of the German power system increased by 5.5 percent to a four-year high (the net effect on German emissions remains unclear). Such a surge, caused by the temporary extension of domestic lignite to compensate for the gas embargo on Russia, highlights that efforts to decarbonize power must be resilient to geopolitics.

-

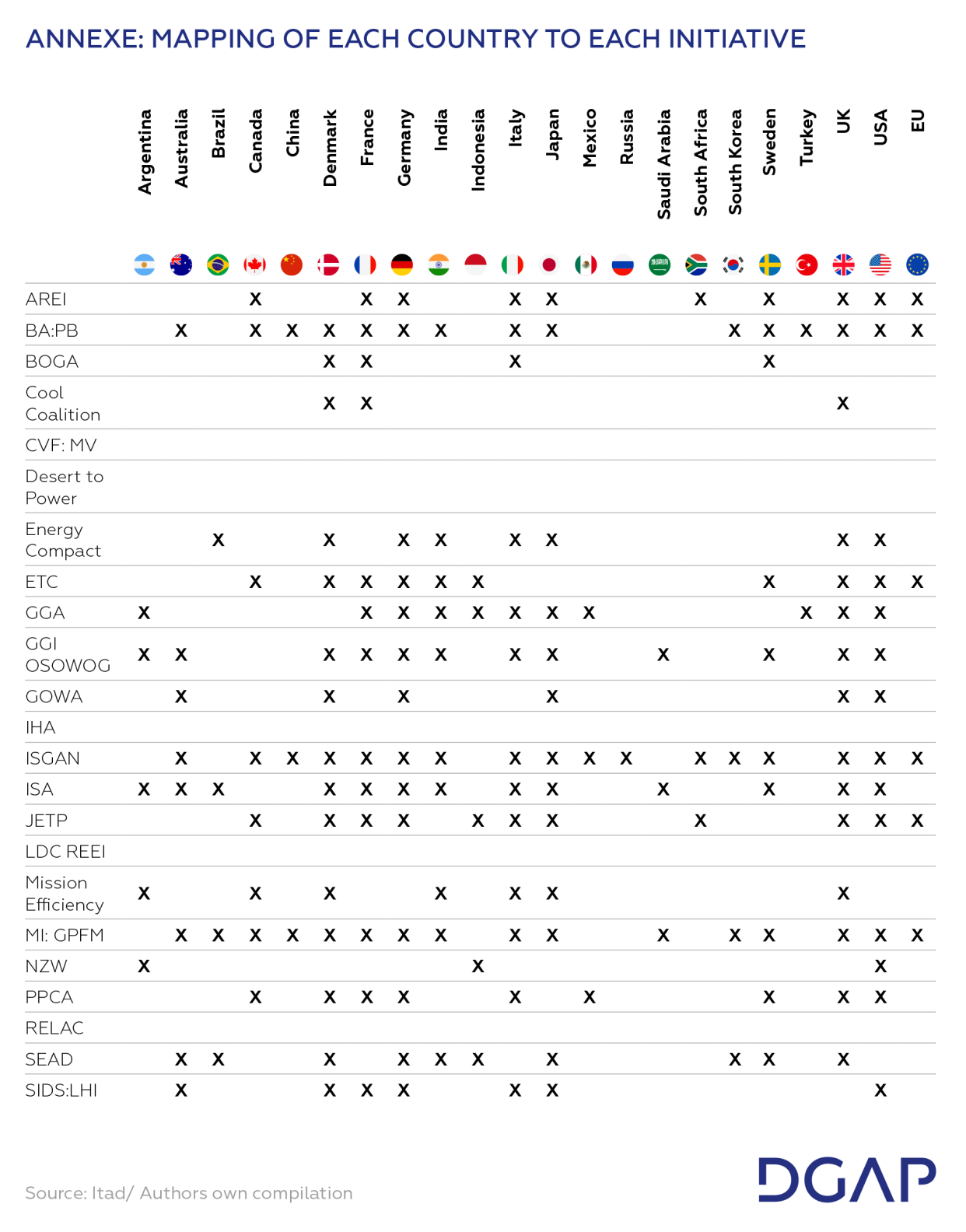

Two tools were used to target the most relevant initiatives: the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) 2021 report “Achieving Net Zero Electricity Sectors in G7 Members” and the UN Global Climate Action Portal (UNCAP). The IEA report highlighted the policy measures and technologies required to enable a net-zero power system. For example, a commitment to stop deploying new coal-fired power stations and deployment targets for new solar capacity. The UNCAP database was used to draft a list of initiatives covering these policy measures and technologies. This assessment examined 23 of the listed initiatives that are based on agreements between multiple governments committed to decarbonizing the power sector and that also have a secretariat (see table).

This brief documents the main countries involved and the success level of the initiatives. The lessons learned from this work should inform COP 28 efforts to triple global renewable energy capacity and double energy-efficiency improvement rates by 2030. The target to “triple up, double down” can serve as a unifying goal for initiatives that cover the power sector. This brief also offers examples of multilateral climate efforts that have delivered results despite enduring a period of geopolitical instability. Donor countries can learn from these examples and thus build ambitious groupings such as the German-initiated Climate Club.

Exploring Initiative Performance

The table below provides a summary of the 23 initiatives and the frequency of the major actors’ involvement. The extent and depth of sectoral commitments is promising. Every enabling measure or technology outlined as necessary to achieve net-zero emissions in the power sector is covered and reinforced by multilateral commitments. (The one exception is hydropower, which lacks a multilateral governmental commitment but has an international industrial association that structures cooperation.) More than half of these commitments also have quantified targets, and while they vary in ambition there are positive results. Some initiatives are well on track to reach their targets or have even exceeded them – illustrating that these climate commitments are reachable and can be even more ambitious. For example, the Small Island Developing States Lighthouse Initiative reached its 2023 deployment targets of 5 GW of renewable capacity in 2019.

Despite the successes, significant gaps have produced mixed results. Data reporting and integration are generally weak. While some initiatives publish reports or update data regularly, this is the exception rather than the rule. Most data are not directly available from the initiatives. In some cases, even when reporting is published, the information is not fully integrated, updated, or utilized to reflect progress. Nevertheless, this does not mean that no progress was made. For example, the last progress report released by the African Renewable Energy Initiative was published in 2017, and while this has not been updated, external data from IRENA shows that the continent deployed almost 16 GW of capacity from 2016 to 2020 and thus greatly exceeded its target of 10 GW.

Additional data points or consulting experts reveals that the implementation of domestic initiatives are advancing targets even when insufficient reporting might suggest otherwise. Moreover, the volume and variety of data available to complement additional analysis illustrates that refining success metrics can improve due diligence, thus allowing success stories to emerge.

Despite this ability to plug gaps with alternative data, the need to do so underscores how they are insufficient. For example, initiatives that determine success by assessing the quantity (GW) of installed capacity alone can miss the details gained by examining more nuanced indicators, such as the project pipeline or curtailment and utilization rates. While this information is available, it is not always easily accessible and might require a more detailed analysis. In any case, this shows that more robust metrics must be used to assess progress. It also infers that there is a possible disjuncture in the feedback loop: between the internationally focused government staff that negotiates these commitments and their respective national counterparts that plan and execute the measures required to reach domestic targets. This indicates that more resources should be allocated to ensure that progress toward commitments is actively reported.

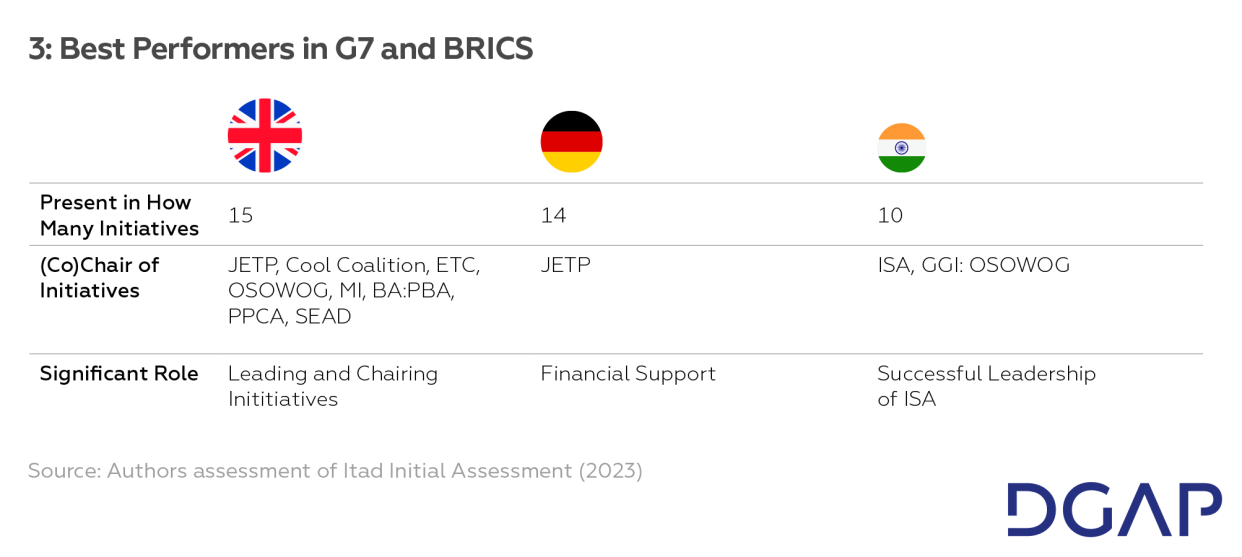

Issues such as reporting vary considerably between initiatives. Their political importance and quality of governance can explain this, in part. It is helpful to have strong, continuous buy-in from a significant actor. India’s leadership role in the International Solar Alliance is a good example. India provided the diplomatic, financial, and physical space to build the ISA near its national lab. Political proximity has helped ensure continued support, which has given the ISA space to build a robust governing structure. The ISA has an annual assembly, standing committees, various regional committees, and hundreds of national focal points. Building networks with a wide range of high-ranking actors and convening them regularly can also build political momentum to act. Furthermore, it creates a dynamic information flow between the initiative and the national context, which enhances their effectiveness in tracking progress.

(Geo)Political Trends in the G20

A closer inspection of the results highlights various trends in international energy policy. This analysis focuses on the G20 because these countries include the world’s biggest economies that are responsible for about 80 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions and account for 84 percent of global power demand. Accordingly, their decisions determine whether global emissions goals are met. Investigating who is engaged where and who is absent helps identify foreign policy priorities.

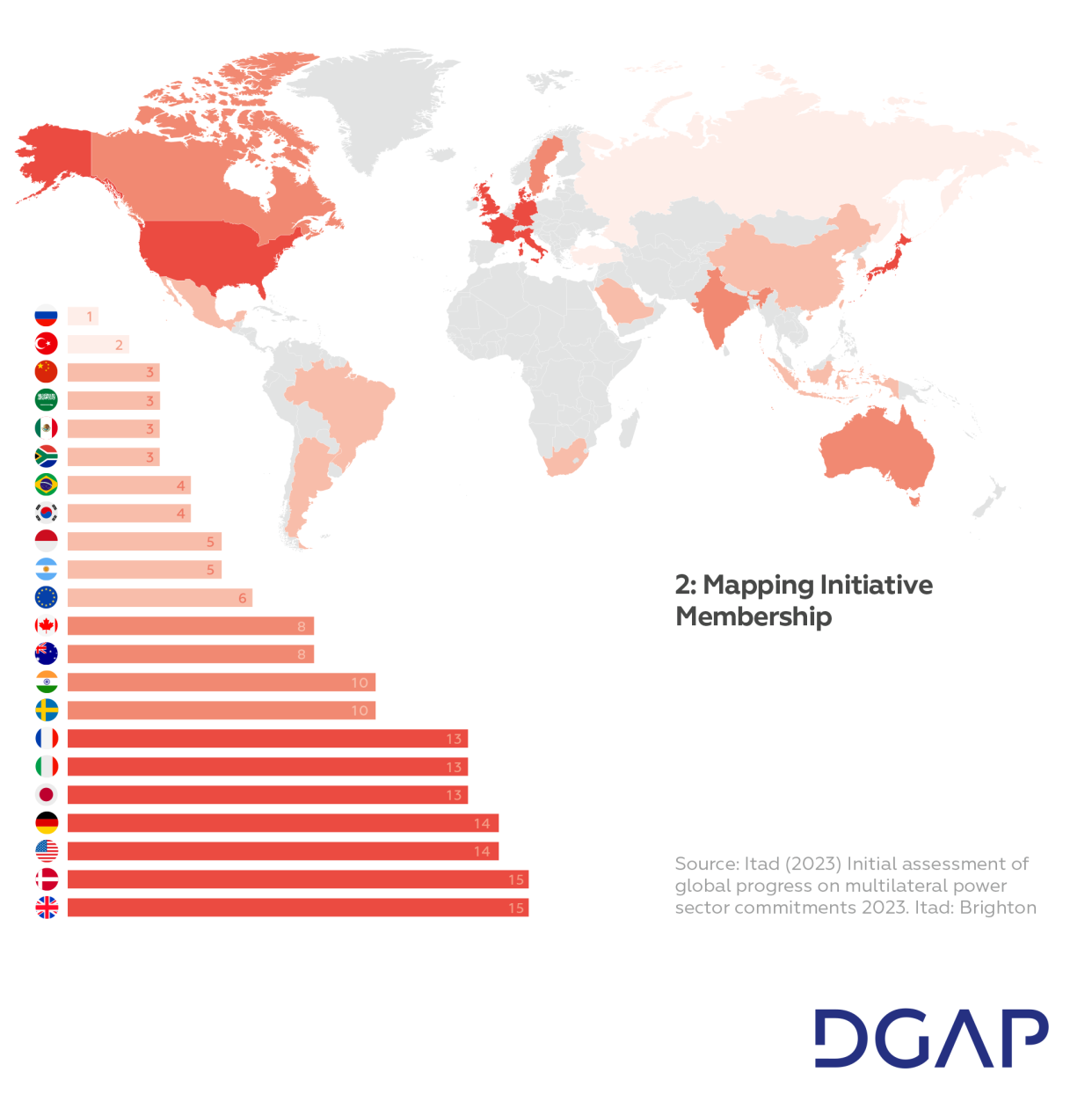

The UK and Germany, which participate in 15 and 14 of the assessed initiatives respectively, are the G20’s most active members. This reflects how Western Europe has actively advanced global efforts to decarbonize through multilateral forums. With presence in eight initiatives for Australia, eight for Canada, and four for South Korea, some Western democracies appear to not be prioritizing decarbonization in their foreign policy like their counterparts. In this case, India’s involvement in ten initiatives and Indonesia in five illustrate good examples of engagement from emerging economies. While participation does not reflect ambition of set targets, a presence in multiple forums affirms commitment to dialogue. It serves to draw a contrast with China’s, Russia’s, and Turkey’s lack of engagement.

The issue of prioritization is even more visible when considering diplomatic and fiscal capacity. Countries like Denmark and Sweden are much more engaged than their economic or demographic size might suggest. Involved in 15 and ten initiatives respectively, they are as well represented as France and Germany. This is partly explained by high fiscal capacity and their prioritization of decarbonization in multilateral forums.

In contrast, China has a large diplomatic corps and is the world’s second-largest economy. Thus it has the means to engage. However, China is mostly absent, indicating that they are not prioritizing decarbonization through the multilateral initiatives that we assessed. Nevertheless, the case of China is more complex. China’s decarbonization agenda is generally focused on domestic goals; policymakers tend not to feel compelled to make sectoral commitments to satisfy international audiences. Moreover, China tends to prefer addressing issues with China-initiated agreements. Some of these fall outside of the scope of the UNCAP and this assessment. For example, the Global Energy Interconnection Development and Cooperation Organization is not assessed because it does not include an explicit commitment. Therefore, poor representation does not fully reflect Chinese efforts to engage multilaterally in power sector initiatives.

The number of countries involved also does not necessarily produce a stronger initiative, especially in the absence of structured financial streams. Very few of these initiatives’ commitments have direct fiscal support, even though finance is crucial for an initiative to function. Also, too many interests force compromises that embrace the lowest common denominator. In this context, plurilateral groupings with fewer highly ambitious countries can be more effective than more inclusive multilateral formats. These agreements are made between more than two countries, and while they are not exclusive they only include actors willing to engage. While these formats do not address the fact that emissions are global – and thus have free riders – a tailored clusters of active countries can deliver transformative results rapidly and still have a high impact, which is an important lesson that helps justify the German-initiated Climate Club.

- How Consistently do Geopolitical Groups Align with Initiative Membership?*

-

Patterns within other groupings are also noteworthy. Countries in the G7 are rarely present in small numbers, primarily due to Europeans’ involvement in the same initiatives, which reinforces the sentiment that this grouping, especially in Europe, has consensus on prioritizing climate issues. In contrast, the only pattern in the BRICS is a lack of engagement. Brazil, China, Russia, and South Africa are cumulatively involved in eleven initiatives. This is nearly the same as India’s ten. This highlights that there is little consistency in this grouping placement of climate on foreign policy priorities.

* Frequency of more than two members being present in a given initiative.

There are also minilateral cases, namely groupings of “the smallest number of countries needed to have the largest possible impact on solving a problem.” These initiatives may be effective at advancing the decarbonization agenda. The Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETP), for example, are agreements that can mobilize considerable capital to address specific issues for high-emitting emerging economies. The opportunity for western capital to shape these domestic energy transitions is geopolitical because of the energy sectors’ centrality to an economy during rapid development. Yet, such agreements are inherently non-inclusive. However, limiting the number of recipients and donors can expedite action to curb global emissions by helping these countries scale up renewable power capacity rather than locking further into coal. For example, Vietnam’s power generation capacity is projected to grow from 69 GW in 2020 to 150 GW by 2030, while India is expected to rise from 425 GW in 2023 to 777 GW by 2030. These additions alone are nearly twice the size of Germany’s entire power system.

Tracking participation across political clusters is insightful. The G20 is most involved in the International Smart Grid Action Network, the International Solar Alliance, the Breakthrough Agenda, and Mission Innovation (refer to annexe). Yet, all of its members are absent from the Climate Vulnerable Forum: Marrakesh Vision, Desert to Power, the Least Developed Countries Renewable Energy and Energy Efficiency Initiative, and Renewables in Latin America and the Caribbean (RELAC). Their absence is to some extent explainable because initiatives are regional or categorically focused for non-G20 countries. Yet, for initiatives like RELAC, the German Agency for International Cooperation, and the US National Renewable Energy Lab offer support through partnerships.

Conclusion

While not all targets have been met, much progress is being made. Yet, the resurgence of geopolitics threatens to undermine cooperation. The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the reignition of frozen conflicts coincides with a fracturing trade system. As the world’s largest economies implement protective support schemes favoring domestic green industry, the Least Developed Countries are becoming frustrated. Not only are they the least responsible for emissions, but they are often also among the hardest hit, and now they risk being locked out of green value chains while China, Europe, and the US vie for supremacy in clean technology. While the unprecedented polarization within and between countries is dangerous, so is the need for swift and coordinated climate action. Climate impacts are global, and therefore no country can justify inaction. Investment in climate action is tantamount to investing in one’s own national security. Yet, unilateral action will not curb global emissions. To address this, this analysis compiled the following key insights:

- Multilateral initiatives have comprehensive coverage over the power sector and some initiatives have yielded positive results.

- Climate action in the power sector is not happening fast enough, despite being the easiest sector to decarbonize. This is because some targets lack ambition and many major emitters remain insufficiently engaged in multilateral initiatives.

- Despite the availability of data, there are many gaps in these initiatives’ reporting. However, the reporting that exists contains rich examples of best practice that countries can learn from.

- Governments continue to demonstrate the will to collaborate on the power sector through multilateral initiatives, even in times of serious geopolitical tension.

- Despite strong engagement from countries like India, there is still a large absence of non-Western engagement in these initiatives, especially from developing countries with significant emissions.

Based on these findings, this brief recommends that:

- Governments should set more ambitious goals. Success stories from the power sector convey an optimistic sense of the possibility to set more ambitious targets. Some initiatives have already reached or exceeded their goals. They can be celebrated as examples that net-zero targets are not only possible, but also realistic.

- Governments regularly provide progress information and data to initiative secretariats. The use of additional data should be normalised to augment indicators and audit progress reporting for initiatives. The power sector has some of the largest data sets available. Yet, there are significant gaps in the indicators used and how reporting is delivered for these initiatives. If this occurred in the power sector, it undoubtedly is occurring in other sectors, too.

- Donors (governmental and philanthropic) should encourage cohesion and ambition around the “triple up, double down” goal by 2030 to unify action among initiatives cover the power sector. Such a broad, overarching sectoral target can help initiatives cooperate and thus maximize their impact by reducing overlapping efforts. More cohesive action oriented toward a common goal can also provide common ground for inter-state cooperation to address common challenges.

- Donor governments and philanthropy provide stronger, more consistent support for secretariats. Doing so will allow them to manage and report on the commitments they are helping governments to implement.

- The foreign policy community mainstream best practices. This includes the like of foreign service officials and civil servants working on climate diplomacy so that existing and new commitments for the power sector and other sectors are well designed, managed, funded, and tracked.