| Migration can be a proactive and successful strategy for adapting to changing environmental conditions if rights protections and other enabling conditions are in place. Governments should assist people to overcome barriers to movement, enabling them to make informed choices. |

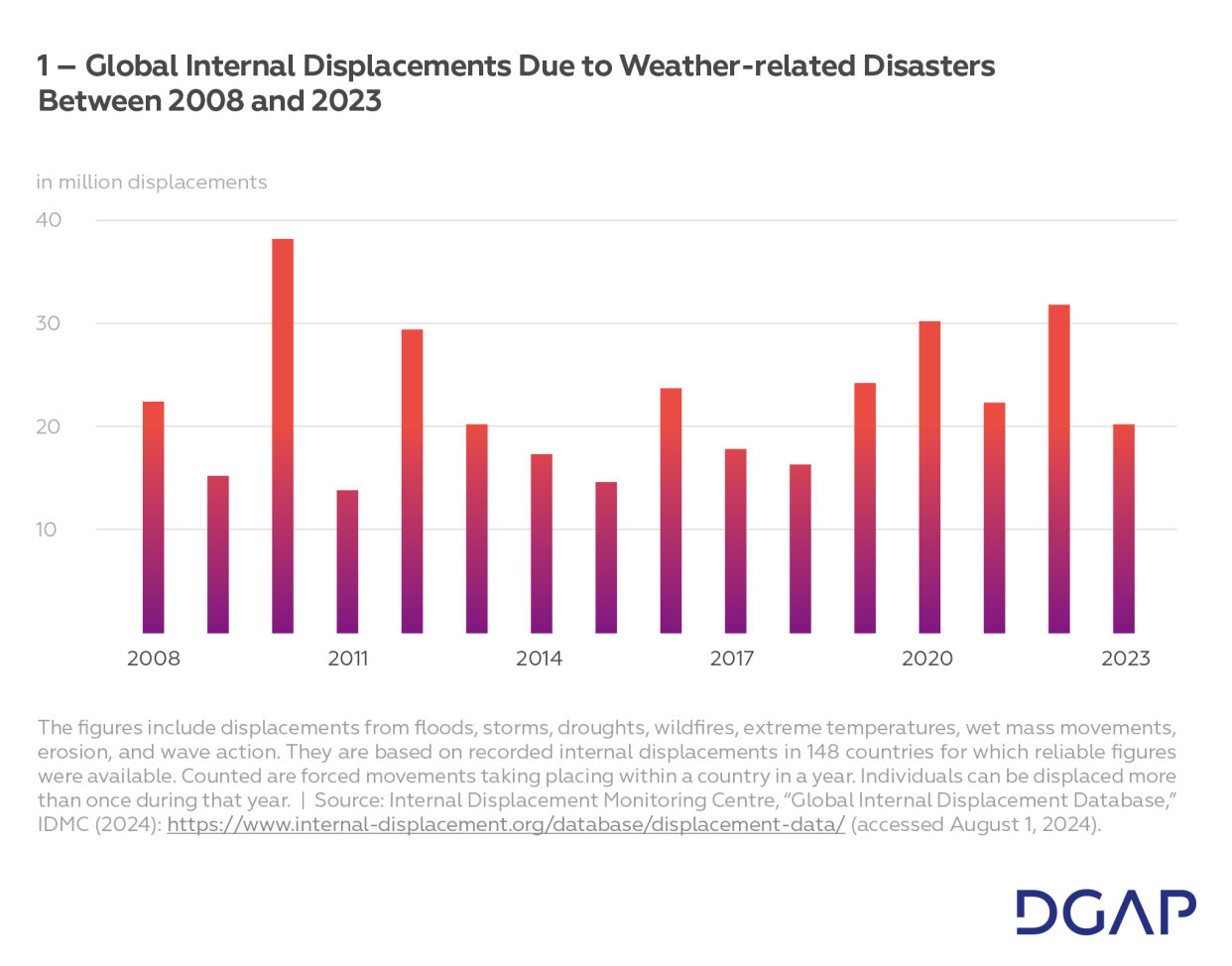

| Cascading and intensifying climate impacts have already led to extensive losses and damages, including displacement. Affected communities need accountable mechanisms and adequate financial resources to address displacement before, during, and after it occurs. |

| The speed and scale of emissions mitigation will determine the severity of ecosystem disruptions and thereby influence drivers of migration and displacement. Realizing decarbonization across different economic sectors will demand skills and labor that many industrialized nations may need to acquire through immigration. |

The online version of this Policy Brief does not contain footnotes. To view the footnotes please download the pdf version here.

In an increasingly complex and polarized world, migration has become a hot-button political issue. The spontaneous arrival of migrants seems to have become emblematic of governments’ loss of control. However, the reality of many types of migration, including climate-driven displacement, looks quite different from the pervasive media images that depict mounting migration crises. Most of the people affected never leave their countries but remain close to home. These migrants remain largely invisible to media attention, and – even more concerning – they have yet to gain significant political attention and support. The failure of the international community to adequately address climate-related migration and displacement renders people vulnerable and, in many cases, unable to respond to and recover from increasing climate impacts. Therefore, this policy brief recommends action across the established communities of policy and practice, aiming to improve realities on the ground and mainstream climate mobility into the action agenda of the international climate negotiations at COP29 in Baku and beyond.

Extreme weather events are already a major driver of forced displacement. In May 2024, floods in Brazil displaced an estimated 600,000 people. In Somalia, prolonged drought followed by flooding led to 1.7 million displacements in 2023. As progress on emissions reductions stalls and losses and damages mount, the divide between small and/or poor countries – that have contributed very little to global greenhouse gas emissions – and the largest polluters is growing.

So, what can be done to formulate effective policy solutions and provide practical relief for affected people? Foresight and planning are essential for addressing the growing global threat that climate change poses to people’s security and their sense of place and belonging. Because human (im)mobility in the context of climate change is such a complex issue, understanding it and ensuring holistic approaches requires insights from several disciplines. This applies to the whole spectrum of mobility forms, ranging from voluntary to forced. Moreover, planning is challenging as the scale involved – that is, how many people may have to or feel the need to move – largely depends on global emission pathways. Ahead of the next international climate negotiations in Baku in November 2024, this policy brief explores how to frame and address climate mobility in the context of different policy discussions around three action areas of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC): adaptation, loss and damage, and mitigation. Through our analysis, we aim to contribute to better outcomes for those too often left out of these discussions.

Climate Mobility on the Adaptation Agenda: Enabling Agency and Pathways

Climate adaptation can take many forms. These depend on the concrete hazards that are being addressed and the economic, technological, financial, and institutional capacities that are in place to form the adaptive capacities of individuals, communities, or whole societies. As such, adaptation is a localized and place-based endeavor that needs to be responsive to context and is closely tied to the level of and approach to development in each country and community.

Adaptation is usually understood as the process of enabling people to withstand hazards where they are – for example, through infrastructural adaptation measures that prevent flooding or reduce heat exposure, or new farming practices that enable people to stay on the land and remain in their place of origin. However, since the beginnings of humankind, people have also used movement, whether permanent migration or seasonal patterns of mobility, to adapt to changes in their environment. Hence, migration is often described as an adaptation strategy that allows households to diversify their sources of income, especially in times of stress.

In 2010, the Cancun Adaptation Framework recognized migration, displacement, and planned relocation as climate adaptation issues that should be addressed through technical cooperation. Since then, driven by the establishment of the Taskforce on Displacement under the Warsaw International Mechanism for Loss and Damage, there has been more momentum for addressing migration and displacement as a form of loss and damage. Conceptually and in practice, human mobility straddles both adaptation and loss and damage as the two are not mutually exclusive. Just as the boundaries between voluntary and forced movements can be blurred, especially in the context of slow-onset changes such as rising temperatures, movements that can be considered adaptive may also involve loss and damage.

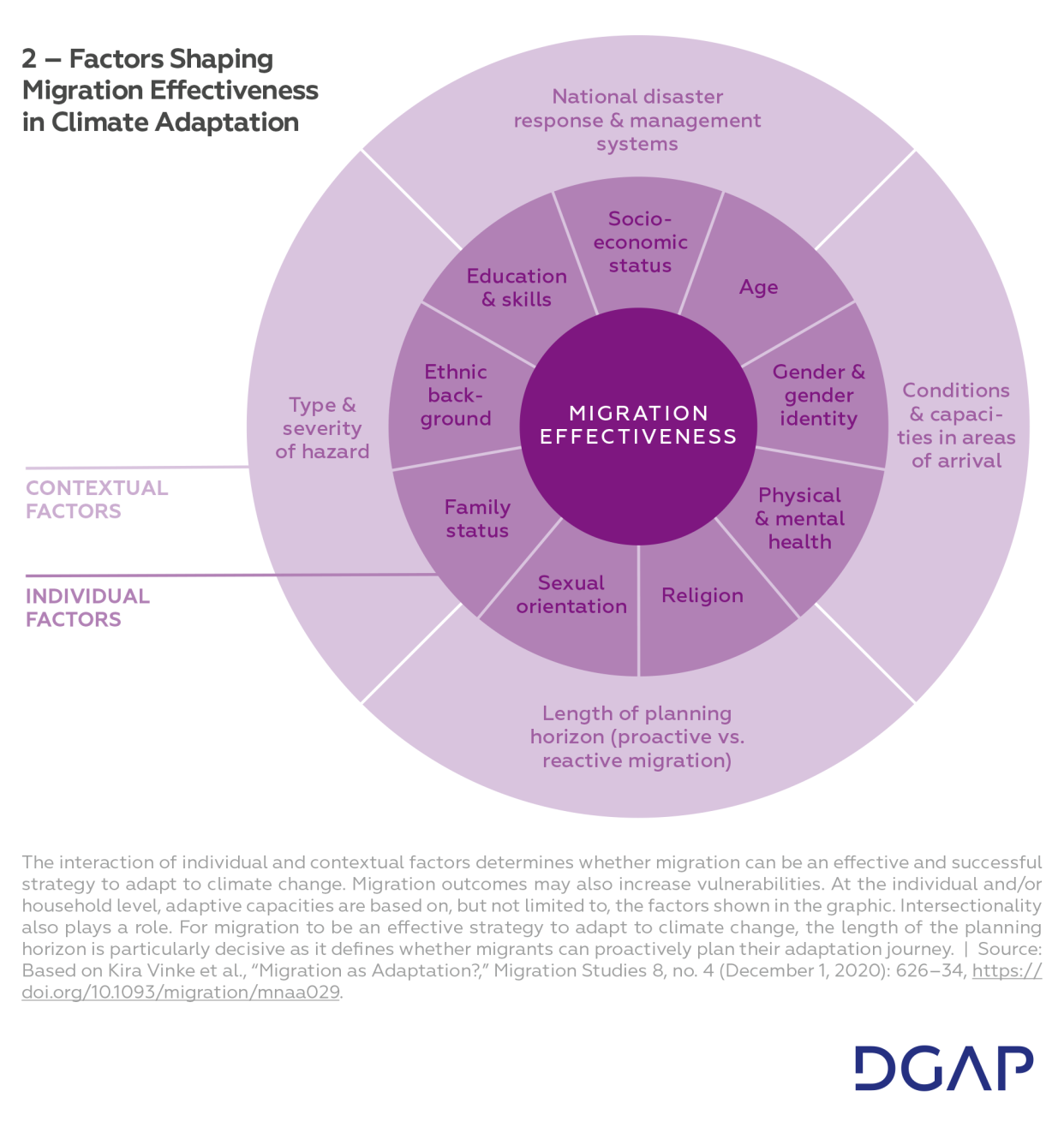

The challenge with characterizing migration as a form of adaptation is that, as with other adaptation measures, its effectiveness is highly context-dependent and based on individual prerequisites and requirements. Which people move, the conditions under which they do so, where they arrive, how they are received, and whether they remain connected to and contribute to their community of origin are all factors that matter. Taking into account the external limitations of people to fully determine their migration outcomes, migration can only be a successful form of adaptation if certain enabling conditions are put into place. These enabling conditions will look differently for different forms of movement – most importantly, for cross-border versus internal mobility. The former will usually entail greater migration costs as well as legal and administrative hurdles related to documentation and visas. Different movers may require specific support systems and protections, e.g., language support for indigenous people, access to reproductive health for women, and guardianship and education for children.

What is at stake in mobility decisions is not just people’s safety but their agency and dignity. Leaving one’s home behind is rarely a matter of individual decision-making. Especially for indigenous peoples, it can pose challenges to preserving their collective identity that involve community and intergenerational ties to the land as well as questions of culture and heritage.

Some countries have begun to grapple with human mobility in their national adaptation plans, yet many still lack concrete policies and actions to address the issue. For the most part, governments remain focused on enabling people to stay in place rather than facilitating their movements. The challenge is to determine where, how, and for how long to invest in resilience-building and when to support relocation as an option instead. These decisions need to be made together with the affected people and communities. If not, they rarely prove effective and may result in people returning to at-risk areas.

Going forward, the adaptation capacities and decisions of countries will be critical in shaping migration dynamics, as well as options for individuals and communities. Admittedly, adaptation measures may be blind to the particular situation of existing refugee and migrant populations. As a history of development-induced displacement suggests, they can also have unintended consequences. Yet, for the moment, with persistent funding shortfalls for adaptation measures in countries that need them most, it is a lack of adaptation investments that likely poses a greater risk.

Migration in the Loss and Damage Debate

For communities at the forefront of climate change, experiencing climate-related loss and damage is a lived reality. The concept of loss and damage, as used in the UNFCCC, recognizes that climate impacts have already caused substantial harm to nature and people, some of which is irreversible. It also acknowledges that some further harm is, by now, difficult to avoid. Losses and damages can manifest in diverse ways. These range from quantifiable and reversible damages, such as damage to a building, to non-economic and irreversible losses, such as the loss of life, health, or indigenous heritage and knowledge.

Loss and damage considerations are relevant for the entire spectrum of more involuntary and forced forms of human (im)mobility – when the decision to move is a last resort for people facing compounding and/or life-threatening risks from climate change and when adaptation in place is not or no longer a feasible option. This may be the case when slow-onset changes such as rising temperatures increasingly put rural and subsistence-based livelihoods under severe stress, or rising sea levels erode coastal areas and contaminate the soil and groundwater. Mountainous communities face challenges when glacial retreat alters the foundation of their way of life in a way that makes adaptation in place nearly impossible.

Others are forced to leave in the aftermath of extreme weather events. In some cases, they have no option to return or require support to move out of harm’s way. Small Island and Developing States (SIDS) in the Caribbean, for instance, are often trapped in a vicious cycle of disaster and debt as they struggle to recover from ever more severe hurricanes. In the Pacific, communities in low-lying SIDS face existential risks from sea level rise that could render entire countries uninhabitable. However, facilitating mobility alone leaves important questions regarding the continued statehood, sovereignty, and collective identity of the displaced people unaddressed.

In a joint report, the Loss and Damage Collaboration and Researching Internal Displacement call displacement “one of the most detrimental outcomes of loss and damage, adversely impacting well-being and the enjoyment of fundamental human rights and potentially reversing development gains for communities and entire nations.” Generally, issues relating to the concept of loss and damage are inherently linked to justice considerations and draw attention to the historical responsibility of industrialized nations for causing the climate crisis. Climate-related displacement exemplifies why this is the case as those least responsible for emitting greenhouse gases may be uprooted from their homes and their communities.

While countries in the Global South are disproportionately affected by climate-related loss and displacement, countries in the Global North must also prepare to face them. In Germany, for instance, at least 135 people died and thousands lost their homes following torrential rains in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate in July 2021. The floods also revealed unpreparedness in managing disaster at the local level as warnings failed in many places. High-income countries, however, are better equipped to financially recover from such disasters.

Financial matters linked to loss and damage have received growing attention in recent years, leading to the operationalization of the Loss and Damage Fund at last year’s COP. Since the funding arrangements explicitly mention “promoting equitable, safe, and dignified human mobility, in cases of temporary and permanent loss and damage,” the Fund may provide much needed mechanisms to finance responses to human mobility in the context of climate change. However, given insufficient funding, a lack of commitment for additional pledges, and delays in setting up the Fund’s operating structures, it remains unclear when and how affected countries and communities can apply for and access funding. Once the Fund starts working, unbureaucratic, accountable, and rapid access that accounts for displacement before, during, and after it occurs will be key.

Climate Mobility and the Decarbonization Agenda

While both adaptation and loss and damage are crucial for addressing harm that already exists or will most likely occur, mitigation targets the root causes of climate change. Emissions mitigation is essential for limiting the risks associated with global warming, including the displacement of people and changes in the boundary conditions for economic development. Consequently, climate protection plays a key role in determining the scale and nature of climate-related mobility. Due to their direct linkages to ecosystem services, rural, low-emissions livelihoods like those based on subsistence farming are often – unjustly – the first to be rendered unviable by climate impacts. This not only creates potential for social friction and migration, but it can also be tied to an accelerated transition to urban livelihoods, which in turn may have a trajectory of higher emission intensity.

For industrialized countries, a core mitigation measure is transitioning to green economies – for example, by enhancing energy efficiency in sectors that are GHG-intensive (i.e., emitting a high level of greenhouse gases (GHGs)) or by switching to renewables-based energy sources. From a climate mobility perspective, green transition processes entail both challenges and opportunities. The extraction of critical minerals for renewable energies or battery production for electric vehicles, for instance, can pose social and environmental risks for local communities. Risks include the abuse of labor rights or water and soil contamination, as is the case with many other extractive industries today. These adverse effects may force people to leave. Yet, the rising demand for critical minerals can also have positive effects in developing countries because it can create jobs, providing people with options for alternative livelihoods. In particular, the creation of local value chains that go beyond the extraction and export of raw materials can serve local development. Besides creating employment opportunities by developing green industry in climate-vulnerable regions, the transition could also open up labor migration pathways to industrialized countries that may foster adaptive capacities through remittances.

On The Road to COP29: Recommendations

When parties gather at COP29 in Baku in November, matters relating to finance and raising ambition for updating the Nationally Determined Contributions will be high on the agenda. While the latter will determine global warming trajectories and thereby climate impacts, progress on finance is crucial for addressing climate migration and displacement. There is, however, a risk of becoming trapped in technicalities when financial modalities are discussed. Addressing climate mobility needs a holistic approach; one that overcomes dividing lines of established communities of policy and practice. Solutions need to be people-centered and account for the different forms that mobility may take – from more voluntary movements to forced ones – in the context of climate change. Coming to such solutions continues to be overshadowed by geopolitical rifts and rivalries that have challenged multilateralism. The following recommendations provide guidance for national and international decision-makers on the road to Baku and beyond:

Adaptation

A repertoire of adaptation measures is needed to strengthen resilience and close protection gaps for climate-related migration. This portfolio needs to extend across solutions for those who want to stay, want to go, or must leave, as well as for those who are already on the move, new arrivals, and those who cannot leave and are involuntarily immobile. Inclusive and participatory processes can ensure that solutions are needs-based and informed by indigenous and local knowledge.

Ensure access to localized data and information on climate risk. Making evidence-based adaptation decisions at the local level requires access to data and information. Governments need to equip affected communities with the knowledge to understand climate-related risks – such as how climate projections might interfere with their ability to adapt in place – in ways that are accessible to them. Vulnerability, risk, and resilience assessments should be done with communities in hotspot areas and include existing populations of migrants, refugees, and internally displaced persons who often have less access to information and a more limited understanding of the local context.

Prepare for community transition in hotspot areas. Climate impacts are not felt equally across the globe. Governments, local decision-makers, and affected communities in places of origin and destination can start engaging in planning and preparedness efforts by using research and modeling that maps current hotspots of climate mobility and projects them for the future. Depending on the context, this may include capacity building measures, technical assistance, technology transfer, and financial resources. The goal should be to create options around staying and/or moving that are built on awareness, rights, and choice and that are simultaneously informed by climate science. Plans should be responsive to the specific needs and vulnerabilities of women and girls as well as potentially vulnerable and marginalized groups.

Develop legal frameworks and policies to govern climate mobility and community relocation. Governments need to ensure that people compelled to move by climate impacts, whether within their countries or across borders, enjoy legal protection. That requires assessing existing protection gaps arising in the context of climate adaptation actions and addressing them – for instance, by creating predictability and clarity around issues such as access to climate risk information, informed consent, meaningful participation, and compensation in the context of planned relocations. Facilitating freedom of movement and other forms of human mobility under regional integration systems and economic cooperation frameworks offers scope for advancing collective resilience by fostering growth and development while also providing a safety valve for people forced to move in the case of disasters.

Loss and Damage

Climate-induced displacement has fundamental consequences that include impacts on human health and well-being. Therefore, interventions to minimize and address forced migration should be a priority. The newly established Loss and Damage Fund needs specific funding lines that make funding available for migrants and refugees as well as those internally displaced by climate change.

Close the finance gap in addressing migration and displacement as loss and damage. While the operationalization of the Loss and Damage Fund is a breakthrough, the mobilization of adequate financial resources for loss and damage has yet to be achieved. Creating a funding strategy that does not depend on short-term voluntary pledges should be a top priority for the Fund’s newly installed board. To help displaced people, particularly in the aftermath of disasters, flexible funding and access modalities are needed.

Acknowledge and address non-economic losses of communities facing displacement. Non-economic losses related to climate change make lasting impacts on communities, including on mental health. For indigenous communities in particular, climate driven uprooting from ancestral lands is leading to the loss of culture and heritage. Yet, measuring such non-economic losses poses significant challenges. To better understand these impacts, standardized methods to measure and track non-economic loss and damage, such as heritage loss from climate change, should be developed jointly with those affected.

Provide individual and collective pathways to protection. While most people prefer to stay, limits and barriers to adaptation may hinder successful adaptation in place or render it infeasible. In such cases, a “climate passport” – built on the idea of the Nansen passport issued to stateless people following the First World War – could be one of the instruments used to enable safe and legal pathways to move out of harm’s way. Bilateral agreements between countries could be pursued to guarantee collective resettlement and a continued right to self-determination for whole nations facing the threat of displacement due to climate change impacts.

Mitigation

To safeguard people’s right to remain in place, limiting climate change as a driver of displacement is crucial. Besides more ambitious and rapid emissions reductions of high-emitters, transition pathways that are beneficial to low-income and climate-vulnerable countries need to be supported. Both measures can have implications for migration and labor mobility.

Facilitate green labor migration pathways to industrialized countries. Legal pathways that enable regular, safe, and orderly migration to labor markets elsewhere diversify adaptation options. At the same time, many industrial countries face labor shortages – also in sectors for transforming and greening their economies. Such countries should be encouraged to initiate pilot projects that target those particularly affected by climate impacts and provide training options for green jobs. The G7 could set goals to create training opportunities and labor migration pathways as an instrument to address both labor shortages and climate-related migration.

Ensure that global efforts to phase out fossil fuels are based on just principles and create jobs and opportunities in developing countries. Trapped in debt and faced with the increasing costs of addressing climate impacts, including displacement, many developing countries do not have the financial and technical capacity to invest in and develop green technologies. To ensure sustainable and green transition pathways everywhere, low-income countries need support to green their economies and create jobs that offer their people opportunities close to home. Such support may include initiatives to monitor the impacts of resource extraction on local communities and ecosystems.