This online text is the introduction to and summary of the DGAP Report "A Digital Grand Strategy for Germany". Download the full report here.

-

- Content

-

Executive Summary

Chapter 1: Digital Sovereignty as Germany’s Leitmotif in a Global Context

Chapter 2: Assessing the Strengths and Challenges of Germany’s Innovation Ecosystem

Chapter 3: Safeguarding Germany’s Technology Stack and Innovation Industrial Base

Chapter 4: Shaping the Global Technology Rule Book in the Service of Europe

Chapter 5: Optimizing Export Control, Investment Screening, and Market Access Instruments

Chapter 6: Strengthening International Technology Alliances, Partnerships, and Norms

Chapter 7: Emerging and Disruptive Technologies, the German Military, and the ZeitenwendeIntroduction: A German Digital Grand Strategy

The Sprint and the Marathon

Digital Sovereignty as Germany’s Leitmotif in a Global Context

Recommendations - Chapters of the DGAP Report "A Digital Grand Strategy for Germany"

Germany is facing an unprecedented era of techno-geopolitical competition. Even amid Russia’s war on Ukraine, rising energy prices, inflation, climate change, and pressure for economic recovery and fiscal consolidation, a burst of development in general-purpose technology is bumping up with increasingly fraught US-China technology competition.

Germany cannot ignore the implications of this. To safeguard its economic and technological competitive advantages, it must knit together its domestic and international capacities and policy objectives in digital technology. The country must do this by anchoring its doctrine of digital sovereignty in six interrelated building blocks based on the principle of “freedom to choose”: supporting an environment for indigenous innovation; promoting open competition of ideas and technologies; establishing clear rules that bring a democratic, human-centric order; restoring informational self-determination to European and global users; limiting carbon emissions and guaranteeing technological sustainability; and implementing penalties with teeth for rule breakers. A “third-way” approach to its digital technology posture – equidistant between the United States and China – is not an option for Germany. Germany and the EU should work with other like-minded states – first and foremost with the United States – to harness their collective weight of market size, access, and innovation industrial bases to tie together the rules, values, and reciprocity that act as mutually reinforcing instruments in a democratic technology governance order. At the same time, Berlin must incorporate stabilizers into its innovation industrial base that protect it, and Europe, from vulnerabilities caused by increasingly tense technological competition between the world’s two great technology powers.

Germany’s success in the ongoing effort to forge a digital grand strategy depends on its ability to foster a “networked mentality” that can establish consensus within the federal government; among national, state, and local policymakers; and between the public and private sectors. While Germany’s August 2022 Digital Strategy represents a good first step toward concrete, measurable objectives for its digital modernization, Germany’s focus remains too domestic, unable to simultaneously address short-term trends (“the sprint”) while developing strategic foresight to plan for mid-term trends (“the marathon”) and their national and international impact. The iterative (Schritt-für-Schritt) approach that has defined German digital policy has allowed four strategic gaps – in data, adoption, investment and commercialization, and cyber – to emerge. The document also remains too narrowly focused on the four B’s: Bund-Land (German federalism); Bürokratie (public administration IT consolidation and digitization); Breitband (broadband and other connectivity infrastructure); and Bildung (digital education). All are necessary but insufficient.

This report takes a systematic approach to outline the state of play in digital policy and Berlin’s current policy approach, and it provides recommendations for strengthening German efforts to build a confident, high-performing European digital economy embedded in an open, democratic, and rules-based digital order. This report puts forward 48 recommendations in seven policy areas that layer on top of each other to build to a cohesive whole, a sort of “technology policy stack.” Together, the recommendations form the basis of an integrated approach to international digital policy that reflects the seven layers of the technology policy stack. The recommendations in the following sections include:

Chapter 1: Digital Sovereignty as Germany’s Leitmotif in a Global Context

Push a clearly articulated “rules-centric” doctrine of digital sovereignty rooted in freedom to choose, open markets, and human rights. As Europe operationalizes strategic technology projects and rules on cloud computing, semiconductors, 5G/6G mobile networks, and quantum computing, the German government must shed a counterproductive ambiguity around the notion of digital sovereignty.

Ensure ministry staff and digital policy units, especially at the expanded Federal Ministry for Digital and Transport (BMDV), think geopolitically. The ministry should establish interagency meetings to assess the geopolitical impact and determine the geostrategic implications of digital and technology regulation and policies. This requires boosting the role of the Federal Foreign Office (AA) and Federal Ministry of Defence (BMVg) in technology policymaking.

Draft a Comprehensive Technology and Foreign Policy Action Plan that links the Digital Strategy with the pending National Security Strategy. As a follow-on to the Digital Strategy, the BMDV, the AA, and the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action (BMWK) should draft an action plan that links domestic and European issues regarding industrial policy for and regulation of the technology sector with foreign policy issues relevant to techno-authoritarianism, setting international standards, internet governance, and technology alliances.

Establish the position of technology ambassador-at-large with three senior deputies that can operationalize German digital technology and foreign policy. The AA should establish an ambassadorship-at-large, with state secretary rank, specifically to marshal this action plan. The structure under the ambassador-at-large should include deputies addressing cybersecurity, the digital economy, and digital rights to guarantee an able, cohesive, international expression of Germany’s technology policy objectives.

Increase the agility of digital federalism. Germany must strengthen the interoperability, innovation complementarity, and technology-security assessments of federal and state (Bund and Länder) governments to build scalable technology on a European and, ultimately, global level. Domestic efforts in this area are, therefore, a foreign policy issue. Germany could, for example, support an “app store” for digital tools related to education, healthcare, and policing. The federal government could also strengthen conditionality among its funding incentives for technology procurement through cyber and vendor guidelines that align with national, EU, and NATO security concerns.

Establish a cross-committee, parliamentary Technology Foreign Policy Working Group. Such a body would ensure consistency in approaches to policy areas ranging from federalism to democratic technology alliances.

Read the complete Introduction to A German Digital Grand Strategy here.

Chapter 2: Assessing the Strengths and Challenges of Germany’s Innovation Ecosystem

Incentivize coordination among innovation-promoting institutions. Germany’s innovation agencies should create a national strategic technology council and a formalized interagency meeting process to compare strategic objectives, test potential cooperation, identify broader obstacles, and consider research into dual-use technology and its applications.

Emphasize complementarity between the Zeitenwende and German innovation in dual-use technologies. The €100 billion Zeitenwende outlay must link defense modernization with basic research and development (R&D) capacity in dual-use innovation, including in defense software. As part of the mentality shift in the Zeitenwende, the Länder and universities must work with the federal government and the private sector on common-sense use of the Zivilklausel.

Commit to reliable capital investment focused on industrial platforms, the Internet of Things (IoT), and deep and green digital technology. Germany should consider a scheme to bundle the Future Fund with institutional investment in an embryonic German Sovereign Wealth Fund, with a proportion of financing specifically directed toward strategically important venture-capital endeavors.

Create sandboxes – research spaces shielded from the constraints of regulation, red tape, and public procurement requirements – at publicly funded research institutions and agencies. Research institutions and innovation agencies would benefit from public sector funding requirements for contracting and tendering, evaluation, and long-term planning that can keep pace with rapid global innovation.

Encourage private sector engagement with “expeditionary investment” in, and acquisition of, technology champions and startups outside Europe. Germany’s leading firms, supported by the German government, need to adopt an expeditionary, or “going-out,” mentality for foreign and direct investment (FDI) to gain access to innovation breakthroughs, diverse organizational and management philosophies, and key intellectual property (IP).

Consider high-end R&D access in geostrategic terms. The government should examine potential defensive instruments to prevent “IP leakage,” particularly in deep technology. These instruments should guarantee, however, the continued importance of Germany’s openness as a global research environment.

Recast the Digital Single Market as a geopolitical priority. Germany should lead efforts to complete the digital single market, including those aimed at encouraging the free flow of data and sector-specific data spaces across the EU. Such efforts should also simplify startup registration and build a unified capital market that encourages cross-border investment.

Consider the information and communications technology (ICT) talent pipeline to be critical infrastructure. Research institutes must offer the computing power, resources, research infrastructure, competitive salaries, and hiring flexibility that their American, British, and Chinese counterparts do.

Read the complete chapter "The Geopolitics of Digital Technology Innovation" here.

Chapter 3: Safeguarding Germany’s Technology Stack and Innovation Industrial Base

Undertake a comprehensive mapping of goals and capacities in critical technology. Mirroring partners’ efforts, the German government should gauge the strength and exposure of key critical technologies in terms of leadership, peer status with competitors, and necessity to mitigate dependency risks.

Increase strategic industrial policy cohesiveness between federal and state governments as well as among the Länder. Germany should prioritize ensuring that states’ industrial policies align with national technology objectives. Senior state officials, research consortia, and industry could use this effort to identify synergies.

Expand transnational industrial consortia in Europe and among like-minded states. Germany should foster cross-border innovation-industrial consortia by advocating a streamlined Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEI) notification process and schemes for foreign suppliers from like-minded states to amplify positive spillover effects.

Focus on domestic – and European – competitive advantages and strategic interdependencies within a larger community of like-minded partners. Germany should design its industrial policy to promote a larger community of like-minded partners that has the EU at its core but includes key partners such as the United States, Japan, and South Korea. The policy should have three distinct goals: IT security, supply chain resilience, and industrial competitiveness.

Structure public procurement to mitigate IT-security and supply chain vulnerabilities. Germany’s largest purchaser of IT systems is its federal government, which can leverage its purchasing power to reduce strategic vulnerabilities, particularly in security-critical layers of its technology stack.

Read the complete chapter "Technology and Industrial Policy in an Age of Systemic Competition" here.

Chapter 4: Shaping the Global Technology Rule Book in the Service of Europe

Address the political trade-offs associated with digital regulation choices. The most difficult aspects of digital regulation often pit key German priorities, such as privacy and security, against each other. Policymakers must be clear-eyed about how they rank objectives when crafting regulation.

Draft model clauses and modules that can be integrated into partner countries’ regulation. This could involve creating an open source regulation repository that expedites the process for non-European partners to achieve adequacy with the EU on personal and industrial data flows, IoT security, and content moderation, and to address challenges regarding the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Conduct geopolitical impact assessments of draft German and European digital regulation. German and EU measures could inadvertently strengthen digital authoritarianism or enable unintended and unwanted global trends such as data localization, censorship, weakened cybersecurity, or internet fragmentation. Candid assessments of the impact of German and EU technology policy outside Europe could anticipate and mitigate such consequences.

Fight creeping state-centrism of European technical standard-setting. Technical standard-setting should not be left solely to the private sector. Yet Germany has an acute interest in balancing private sector leadership with national and European interests.

Bolster private sector technical standard-setting capacity. Germany should introduce tax incentives and public funding mechanisms for domestic companies, startups, and associations to participate in standard-setting bodies, seek chairmanships, field draft standards, and work with like-minded states.

Embed high European Cloud Certification and Gaia-X Architecture of Standards into global cloud governance efforts. As industrial data could become a new frontline in global technology regulation, Germany should examine ways to internationalize its data space model, Gaia-X, to include non-European powers, especially the United States. Germany should also support building the capacities of Global Gateway partner countries to use European cloud computing architectures, thereby increasing interoperability and safeguarding human rights.

Integrate digital regulation and technological standard-setting into the Zeitenwende and the National Security Strategy. Germany must consider more intently the effects of digital regulation on its national security posture and defense industry. The country must ensure it can adopt and deploy dual-use technology on par with peer nations such as France, Canada, Japan, and the United Kingdom.

Increase the engagement of Germany’s foreign policy and national security communities in shaping and enforcing regulatory agreements. German intelligence, foreign policy, law enforcement, and defense agencies have roles in enforcing national technology regulations. It is time for these authorities to assume more prominence, including in the post-Privacy Shield Data Privacy Framework (DPF) era.

Establish a multistakeholder approach that incorporates civil society, the private sector, and other non-state actors. Germany – and Europe – have begun pioneering new models of managing and enforcing technology regulation. Such flexible structures allow for constant oversight that is subject to compromise.

Expand reviews and sunset clauses in digital regulation to encourage flexibility. Review and sunset clauses would compel regulators to consider the effectiveness and relevance of rules. Such clauses would also support consistency with regulation in other democracies.

Read the complete chapter "Germany’s Role in Europe’s Digital Regulatory Power" here.

Chapter 5: Optimizing Export Control, Investment Screening, and Market Access Instruments

Work with allies to create a 21st-century Multilateral Technology Control Committee. The new body, which could be incubated in the EU-US Trade and Technology Council (TTC) or the G7, would systematize information sharing and coordination on restricted access to strategic technology by authoritarian states such as Russia and China. Its remit should include information-sharing dashboards and recommendations on dual-use export and import controls of critical technology, investment screening, trustworthy vendors, and research protection.

Create Foreign-Direct Product Rule and “Entity List” Instruments for Germany. Germany has many key, hidden levers in high-tech value chains. Such instruments can help the country prepare for future potential chokepoints in quantum technology and biotech, sectors in which Germany could have important niche supply chain capabilities.

Start an action-oriented policy debate on research and outbound investment governance. With EU and NATO partners, Germany should look at proportionate means to monitor and evaluate outbound investment behavior in autocratic regimes while continuing to defend open investment markets. The Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) should further anticipate EU action on research integrity by creating review guidelines and making them publicly available.

Expand trustworthiness assessment processes beyond 5G mobile network equipment. The German National Security Strategy should allow for deeper development of national instruments to restrict the use of certain technologies (e. g., smart cities, screening, AI, and satellite technology) on the basis of political and security considerations. These schemes should differentiate between NATO, EU, and bilateral treaty allies and consolidated democracies on the one hand and non-EU/-NATO and authoritarian states on the other.

Encourage European participation in emerging Indo-Pacific technology access and control arrangements. Greater strategic convergence between Europe and other key democratic actors is crucial for creating among them a robust, reliable market for critical technologies such as semiconductors. Through the EU, Germany should push for Europe to be an active part of enhanced geo-economic and technological engagement in the Indo-Pacific.

Read the complete chapter "Germany’s Economic Security and Technology" here.

Chapter 6: Strengthening International Technology Alliances, Partnerships, and Norms

Advance the notion of a democratic technology trust zone. This trust zone would regulate flows of skills, capital, and data to boost competitiveness and trustworthiness for strategically important ICT infrastructure such as network equipment and that for cloud/edge service providers and smart city applications.

Establish a global connectivity doctrine with open internet access as a fundamental right. Germany should work with EU member states and other like-minded democracies to devise jointly financed “connectivity packages” that bundle digital infrastructure assistance with cyber capacity-building. Cooperation should also be established to narrow the digital divide in the Global South and maintain open information flows during authoritarian-driven internet shutdowns and in conflict zones.

Create a German Open Tech Foundation (GOTF). The recently launched Sovereign Tech Fund should be complemented with a German Open Tech Foundation to provide international funding for the development of democracy-affirming and privacy-enhancing technologies in line with the government’s understanding of digital sovereignty. This funding should be directed primarily toward communities in the Global South.

Counter politicization of critical and emerging technologies standard-setting. As the weight of non-market economies in standard-setting bodies (SSBs) grows, Germany should initiate an international study group that identifies whether and which political instruments may be used by such actors to capture standard-setting for critical and emerging technologies. This should form the basis for coordinated engagement with SSBs on ensuring the primacy of technical criteria and preserving the SSBs’ reputation for impartiality.

Work to avoid the emergence of a digital Non-Aligned Movement. In 2022, Germany has already revived its digital dialogue with India and included the country in this year’s G7 guest list. Given India’s 2023 G20 presidency, Germany should now build on its engagement to emphasize India’s democratic responsibility to champion an inclusive digital agenda centered on climate-friendly technology, and open and free connectivity.

Engage collaboratively in EU-US technology dialogue, especially in the TTC. Germany should create a bilateral digital dialogue with the United States that can align and amplify policy deliverables from the TTC.

Create asymmetric technology alliances with subnational governments. Cities and states are increasingly assuming digital governance responsibilities that national governments are unwilling or unable to undertake. Germany, in line with the European Council’s new digital diplomacy conclusions, should work with subnational governments to build technology alliances that reflect German and EU regulatory values, and support subnational adoption of cyber and internet governance norms.

Read the complete chapter "Germany’s Global Technology Diplomacy" here.

Chapter 7: Emerging and Disruptive Technologies, the German Military, and the Zeitenwende

Commit two percent of the €100 billion Sondervermögen to fostering disruptive defense R&D. The German government should commit at least two percent of the Sondervermögen to acquiring disruptive defense technologies. This would incentivize venture capital funding for new defense startups and increased R&D spending by Germany’s established defense companies.

Connect the ethical debate on military EDTs to operational realities. High-level discussions on ethics in Germany are frequently disconnected from operational realities. Debate should focus on appropriate degrees of machine autonomy and justifiable purposes for the use of EDTs.

Link dual-use implications of EDTs with innovation industrial policy. The new National Security Strategy should include a section unifying technology and innovation industrial policies, including those relevant to defense, and link them to a governmental assessment of key national security threats.

Augment knowledge transfer among military and civilian R&D. The German government should expand links between the Munich-based Digitalization and Technology Research Center of the Bundeswehr (dtec.bw) and Bavaria’s high-tech startups. The government should facilitate a separate Track II platform for innovators that facilitates discovering dual-use applications for EDTs developed with the support of innovation agencies, including SPRIND and the Cyber Innovation Hub. The government should also create incentives, such as fund matching, for German and European venture capital investment in defense technology startups.

Align defense procurement with technology innovation cycles. Defense budget fluctuations stifle the ability to support lengthy EDT innovation cycles. The government should establish a dedicated fund for disruptive defense technology with annual minimum budget guarantees through 2030.

Maintain allies’ interoperability through joint principles and military formations. The German government must ensure that EDT-related transformations do not undermine interoperability with allied forces. It should promote development of common ethical principles and codes of conduct, such as those defined in NATO’s AI strategy.

Read the complete chapter "Ethical and Operational: the German Military" here.

Introduction:

A German Digital Grand Strategy

The Sprint and the Marathon

Geopolitical competition between incumbent and rising powers, democratic and authoritarian systems, and rules-oriented multilateralists and power-based unilateralists has led to a marked increase of weaponized interdependence. Germany – and Europe – are confronted with a new reality in which access to and control over flows, hubs, and choke points – in trade, finance, energy, raw materials, oligarchic networks, and even food – are being deployed as part of an arsenal of low-intensity global conflict.

This is especially true in technological connectivity. The United States, China, and their Big Tech affiliates in AI, Cloud, platform, chip technology, and elsewhere have asymmetric control of key nodes. The increasingly general-purpose nature of certain foundational technologies for economic, political, and military competitiveness sharpens the inherent dangers of this situation for Germany and Europe.

Against this backdrop, Germany has begun to grapple with a new whole-of-government approach to digital technology. In August 2022, the German cabinet agreed to a first-of-its-kind Digital Strategy. The strategy, written by the BMDV, focuses on three action areas: a networked and digitally sovereign society; innovation in the economy, the workforce, science, and research; and the digital state. The strategy also establishes a number of concrete “Enabling Projects,” particularly on norms and standards, data availability, and digital identities.

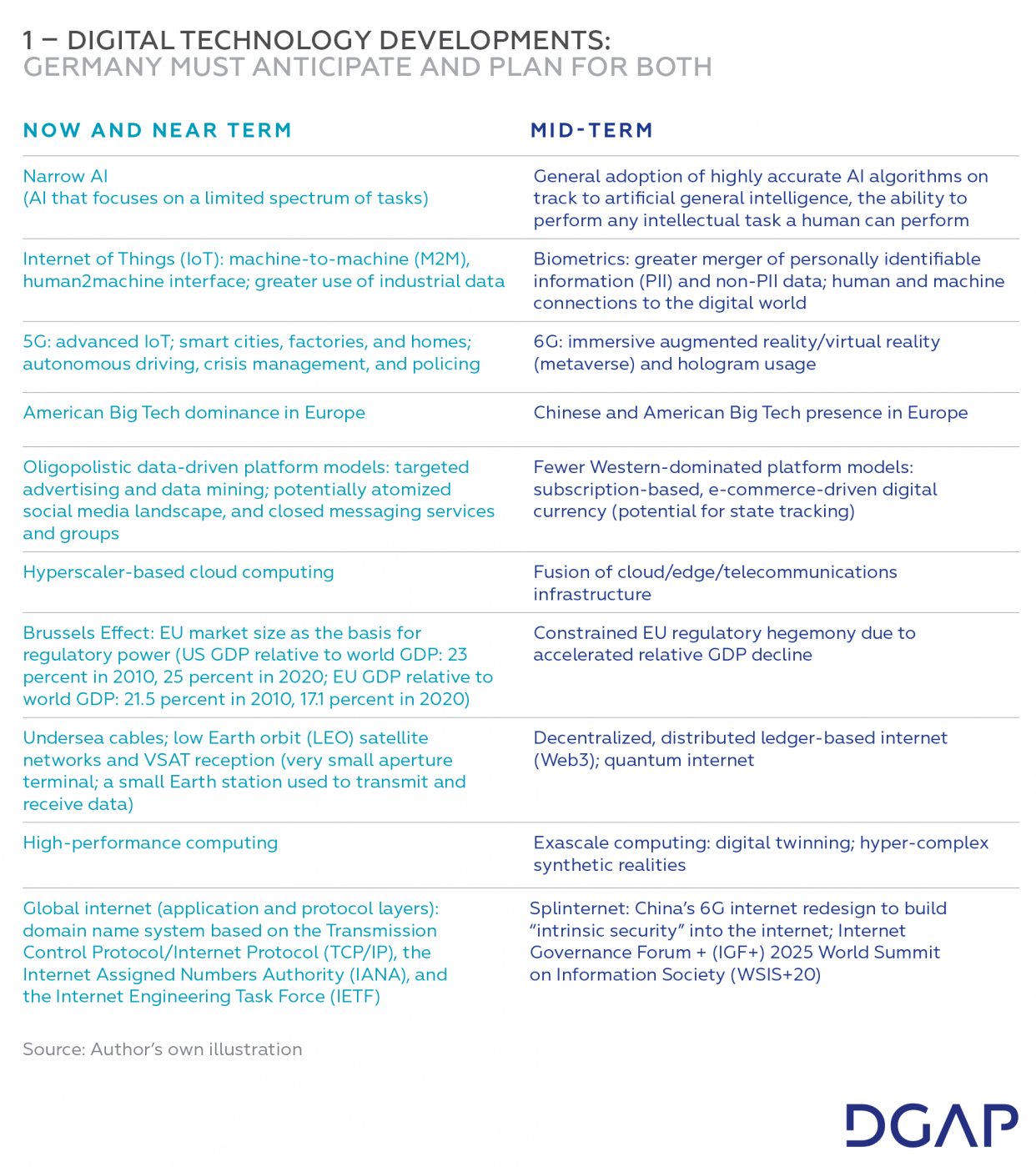

But even as Berlin’s Digital Strategy begins to tackle the need to break ministerial silos and integrate the private sector into a federated policy approach to digital technology, Germany remains too disconnected from the geopolitical threats that already confront it. It falls short in anticipating technological developments and preparing for them in line with Berlin’s policy objectives (see Figure 1). Recent German governments’ cautious digital policies focused preponderantly on near-term digital conditions, and these policies proved insufficient for addressing emerging challenges, such as the impact of new technologies on innovation, the industrial base, and an international system inextricably linked through technology, economic competitiveness, ideology, and security. As such, these policies also constrained the ability to anticipate and shape important mid-term technological developments.

Moreover, German digital policymaking often exhibited a geographic myopia, characterized by a heavily domestic focus. To its credit, though, Germany’s 2022 Digital Strategy attempts to break the narrow fixation on the infrastructure that enables digitization, with the following areas, or four “B’s,” at its core:

Bund-Land (German federalism): establishment of an agreement among the national and Länder (state) governments on interoperable approval processes, IT interface standardization, and public administration multi-cloud strategy

Bürokratie (public administration IT consolidation and digitization): government portals for submitted materials that will be interoperable with EU systems by 2025; establishment of a public administration cloud strategy (the Deutsche Verwaltungscloud-Strategie or DVS) and criteria for sustainable data centers based on secure and, ideally, open source software and data storage procurement standards; e-ID standards; publicly available data and implementation of the Open Access Law (Online-Zugangsgesetz or OZG)

Breitband (broadband and other connectivity infrastructure): expansion of Germany’s 7.5 million fiber optic connections to cover rural regions through the “White Spots” program; mobile connectivity in rural areas and on public rail; extended spectrum licensing; a Gigabit-Grundbuch (gigabit register that contains information relevant to enlarging digital infrastructure) with clear guidelines for expanding ICT connectivity infrastructure

Bildung (digital education): Digital Pact 2.0 until 2030 with cloud and software tools in a so-called National Education Platform based on Gaia-X and hardware maintenance; building on digital tools available to the Länder

While this is all necessary, Germany is coming to terms with the reality that an approach centered on the four B’s is insufficient. The German government – in collaboration with the domestic private sector, research community, and civil society – must strengthen its ability to anticipate and react to developments in the short term (the “sprint”) while developing strategic foresight to plan for mid-term trends and their impact (the “marathon”). Balancing the two undoubtedly poses challenges for policymakers. Too great a focus on short-term issues risks insufficient digital planning. Too great a focus on the mid-term risks overlooking the steps needed to undertake immediate action.

The friction between near-term and mid-term technological development extends to the German private sector’s approaches to digital policymaking. This has led to the emergence of four gaps vis-à-vis xglobal peers that must be addressed:

Data gap: Studies on the direct impact of the the GDPR and other data regulation on innovation in Europe are inconclusive. At times, this regulation slows the availability and velocity of data processing. At other times, it opens new avenues for innovation. But the depth of European data markets remains limited compared to that of other democracies, such as the United States. Moreover, the push for greater data localization – within the EU and globally – could exacerbate this trend. Efforts to encourage data altruism at the European level (through the Data Act and Data Governance Act), emancipate public data for commercial use, and push data spaces in areas such as health and mobility are all promising. But they remain aspirational. At the same time, data sharing faces a cultural barrier.

Adoption gap: German industry, particularly its Mittelstand and small businesses, continues to lag in cloud adoption, which is increasingly the gateway to industrial digitization and to the platform on which other digital services in AI, cybersecurity, and data analytics become available. Germany as a whole ranks 20th out of 27 EU member states on cloud adoption. German industry’s ability to withstand the blow from its slow adoption of the initial software and internet revolution was possible because its niche capabilities preserved their global competitiveness. And yet, the potential impact of emerging technologies beginning to sweep across industries represents a significant – if not existential – risk to some core business models.

Investment and commercialization gap: While the government aims to invest upp to 3.5 percent of GDP in R&D, private sector-driven R&D is leading emerging-technology investment outside Europe. The US has 50 percent of top private sector investors in quantum computing. China has 40 percent. Europe has none. Europe attracts only 12 percent of global AI private sector funding compared to the United States’ 40 percent and Asia’s 32 percent. The commercialization mismatch is clear: Europe is leading in patents in only two of ten key enabling technologies. This occurs even as basic research output in Europe, with Germany as its leader, remains on par with the United States and China.

Cyber gap: Persistent incidents in German IT systems – involving IP theft, ransomware attacks on municipalities and hospitals, politically-motivated hacks such as the 2021 Bundestag election interference, and unintended collateral damage – have intensified since the pandemic. The volume and sophistication of attacks by state actors, such as China and Russia, and by state-adjacent and non-state actors are increasing. Germany has been at the forefront of drafting cyber controls and standards to confront this changing threat environment. Within the EU, Germany is signaling the multi-domain consequences – from sanctions to attribution – for below-threshold action through the Cyber Diplomacy Toolbox. Outside the EU, Norway’s Sovereign Wealth Fund has acknowledged that cyber security is a leading source of systemic economic risk.

In each of these four instances, Germany’s previous iterative (“Schritt-für-Schritt”) approach proved ill-equipped to address emerging challenges such as the impact of new technologies on innovation and the country’s industrial base, and an international system inextricably linked through digital technology, economic competitiveness, national security, and, increasingly, ideology. Success in these areas will come only if Germany ultimately shapes a confident, high-performing European digital economy embedded in an open, democratic, and rules-based order. The need to achieve this is particularly acute as prospects grow for internet fragmentation, data localization, and a growing role for technology in exporting governance models. The need is also acute because digital dependency is a geopolitical vulnerability.

Digital Sovereignty as Germany’s Leitmotif in a Global Context

To tackle the four gaps, and near- and mid-term technological development, Germany needs an integrated approach that knits together its domestic and international digital technology capacities and objectives. Such an integrated strategy requires the attention and support of representatives across policymaking institutions including the Bundestag, ministries, the EU, the Länder, the private sector’s incumbent and startup communities, and other partners in Europe and beyond. This is the only way to forge common goals and approaches.

Germany should give allies and adversaries alike a clear understanding of the comprehensive whole of its international digital policy. This policy should be embedded in Germany’s role as a leading EU member and built around six interrelated building blocks based on the principle of “freedom to choose”:

Supporting an environment for indigenous innovation. The policy should create stronger links among state-backed R&D efforts, commercialization, and industrial policy in emerging technological areas such as AI, quantum, advanced chips, and cloud computing.

Promoting open competition of ideas and technologies. The policy should avoid lock-in effects and diversify vendors to build supply resilience into critical technology and raw materials sourcing. It should build strategic interdependencies with like-minded states, pragmatically promote open source software, force proprietary systems to become interoperable, and privilege a bottom-up, multistakeholder approach to setting standards.

Establishing clear rules that bring a democratic, human-centric order. The policy should regulate content moderation, market power of online platforms, industrial data, cybersecurity, cloud rules, and AI to instill digital trust among Europeans and to create a global model. It should restore German and European capacity for setting technical standards.

Restoring informational self-determination to European and global users. The policy should promote data protection, end-to-end encryption, and content moderation without significantly encroaching on free speech. It should advance freedom to choose as a core principle of ICT infrastructure cooperation with the Western Balkans, Eastern Partnership countries, and the Global South.

Limiting carbon emissions and guaranteeing technological sustainability. The policy should encourage the use of emerging technology that is “Green by Design”, with CO2 reduction at its heart. Such technology includes cutting-edge chips and closer-to-the-source computing, energy-efficient algorithms, AI-powered energy optimization in IoT, and quantum modelling to optimize sustainable agriculture.

Implementing penalties with teeth for rule breakers. The policy should apply proportionate sanctions, investment restrictions, export controls, and loss of access to IP, data, and markets to states and technology companies – including gatekeeper platforms, telecommunication and internet service providers, hardware providers, and messaging services – that violate rules.

This approach is not as evident as it seems. The EU in recent years has balanced two conceptions of digital sovereignty and occasionally papered over deep internal tensions concerning the bloc’s strategic direction in this area. The ordoliberal tradition forms the basis of a “rules-centric” approach that centers on strong support for competition, clearly defined regulation, fundamental rights and open markets, and an antipathy toward network effect-based cartelization, lock-in effects, and barriers to cross-border digital services. This school of thought also rests on a multidimensional understanding of sovereignty in which the state, institutions, and individuals all have a claim to digital self-determination. Some of Germany’s partners, notably France and parts of the European Commission, however, endorse the other conception that involves a more “player-centric”, interventionist notion of digital sovereignty centered on technological import substitution industrialization (ISI), protective tendencies, and data localization within Europe.

Both conceptions of digital sovereignty have at their heart a completion of the European Digital Single Market and scalability across Europe. Both see strengthening domestic innovation capacity and reducing external vulnerabilities as strategic objectives. Both also place greater emphasis on a state interventionist role in shaping the ICT environment. But as long as both traditions co-habitat in Europe’s approach to digital sovereignty – papering over core tensions and contradictions – it delays, at times, hard choices about strategic policy for the sake of consensus building.

First, it strengthens a logic of digital sovereignty centered on domestic localization of data, social media, digital services, and strategic technologies to bolster industrialization and political control. This path can lend legitimacy to more authoritarian notions of digital sovereignty, such as those Russia and China promote, that allow a strong, centralized state to permeate all aspects of life to maintain order. This also risks encouraging global digital mercantilism, which carves the world into digital service and data spheres of influence that could bar European rules and players from other geographic regions.

Second, the third-way approach can limit freedom of choice by restricting technologies, and data and digital services, that benefit users and the innovation industrial base. The global slide toward data localization, a splintered internet, and closed technology stacks carved into regional or national spheres of influence should worry European policymakers. Their counterparts in New Delhi are already responding to this trend with calls for an Indian “fourth way.” Other aspiring digital powers could follow suit. If the world falls into internet regionalism and digital mercantilism, Europe, with its dependence on US digital services and East Asian hardware, would find itself at an even greater disadvantage than it does now as it tries to build its own capacity in areas including IoT, the industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), and emerging technologies such as quantum computing, blockchain, and AI. Moreover, it could lead to digital protectionism that cuts off other open digital markets, potentially robbing Germany and the EU of access, innovation, and partners in governance.

These are all threats to German – and European – digital sovereignty, which must build on concepts that are inherently universal to maintain its power. Digital sovereignty must center on individual emancipation in a global, democratic values system, even as it aims to enhance German and European technological competitiveness and resilience.

To that end, Germany and the EU should work with other like-minded states – first and foremost with the United States – to harness their collective weight of market size, technology access, and innovation industrial bases. Such cooperation could also ensure openness by tying together the rules, values, and reciprocity that act as mutually reinforcing instruments in a democratic technology governance order.

In short, a “third-way” paradigm that lends itself to equidistance between the United States and China is not an option for Germany. But as Germany stands with like-minded states, first and foremost the United States, it must also build in technology industry stabilizers that protect it – and Europe – from vulnerabilities caused by an increasingly tense technological competition in which Europe aims to play a leading role. This means creating new instruments for reciprocity, market access, and technology alliance formation, and new thinking about R&D for general-purpose technology.

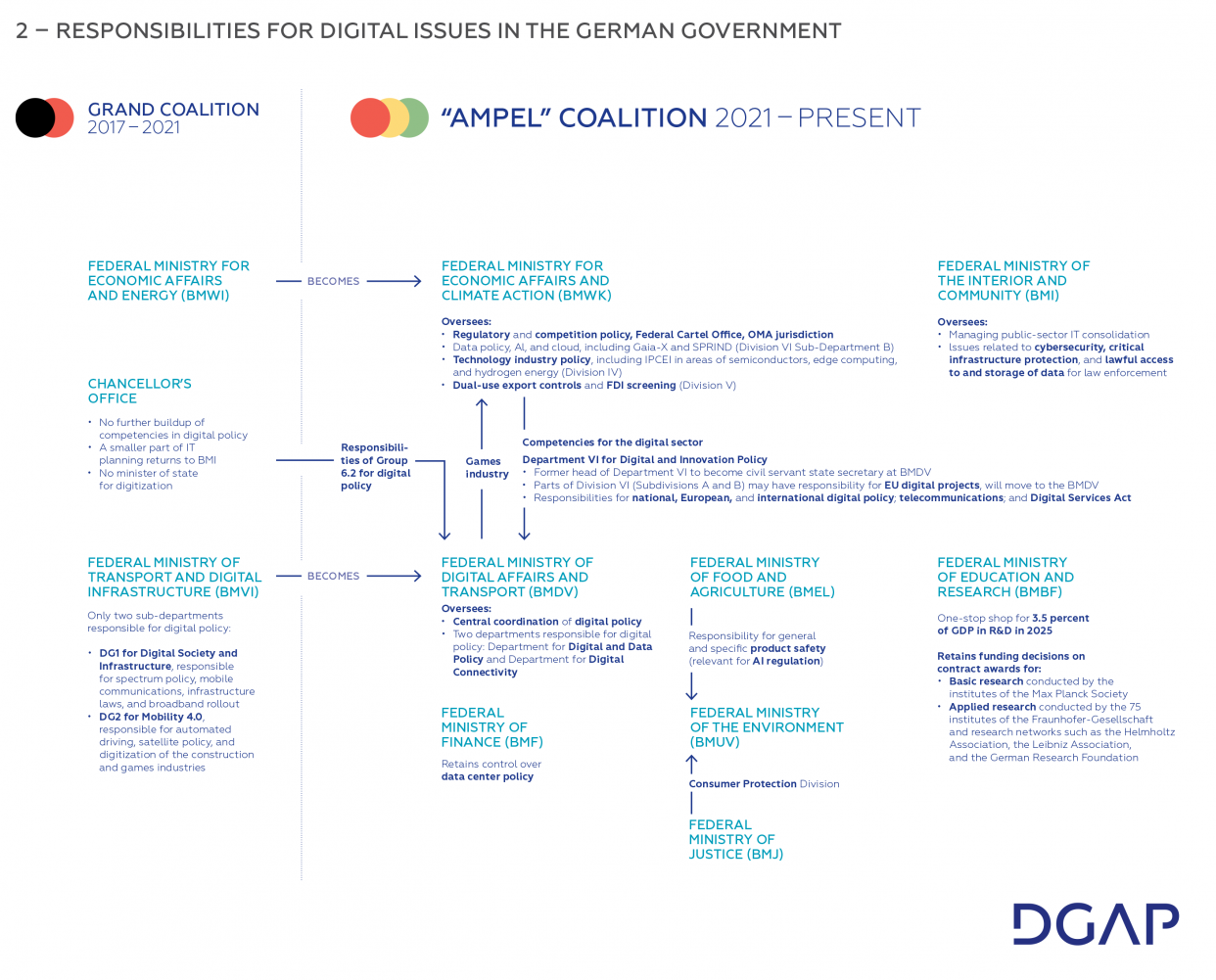

Fit-for-Purpose Policymaking Structures

In the past, the differentiation of policy areas and diffuse responsibility across ministries has hindered effective, coordinated action that integrates R&D, industrial policy, regulation, and values into a coherent posture that promotes Germany’s economic competitiveness, national security, and democratic values. The current coalition government has attempted to reform past structural weaknesses across ministries with the aim of streamlining policy and budgeting for digital issues (See Figure 2). But the need to accommodate three parties divided responsibility for technology so that it is now more widely dispersed than in prior governments. The outcome, at least as seen in the coalition agreement, likely poses significant hurdles for establishing a clearly defined vision for Germany’s digital transformation and, therefore, a strong international position in the global technology race.

The BMWK controls digital competition policy and the Federal Cartel Office (Bundeskartellamt). It oversees implementation of the Digital Markets Act (DMA) and has important responsibilities concerning data governance, AI, and the cloud, including Gaia-X and SPRIND, Germany’s experimental technology hub. It manages industrial policy for the technology sector, including EU-level IPCEIs in areas such as semiconductors, edge computing, and hydrogen energy. It also retains foreign economic policy, with control of the most important instruments for overseeing technology, national security, and trade. These instruments include dual-use export control, and foreign and direct investment screening regimes. All these levers are critical for shoring up Germany’s and Europe’s capacity to shape digital policy and digital sovereignty.

At the same time, the BMBF maintains crucial decision-making authority for funding and contracting for basic science at institutes such as the Max Planck Society, and for applied science at the Fraunhofer Society’s 75 institutes, the Helmholtz Gemeinschaft, the Leibniz Gemeinschaft, and the German Research Foundation (DFG), among others. The BMBF leads the way, with the BMWK, on shaping the new Agency for Transfer and Innovation (DATI), but the latter also oversees efforts to raise R&D spending to 3.5 percent of GDP by 2025. Meanwhile, management of public sector IT consolidation, cybersecurity, protection of critical infrastructure, and lawful access to and retention of data for law enforcement remains under the auspices of the Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community (BMI). And the Federal Ministry of Finance (BMF) retains control of data-related policy, which is crucial to data infrastructure affecting data localization, industrial planning, and the terms under which American and Chinese hyperscalers can participate in public sector cloud service offerings.

The government’s decision to outsource all digital responsibility and devolve coordinating staff formerly housed in the chancellery is fueled at least in part by a sense that Germany’s digital transformation stagnated in the Merkel era. The decision could be a step backwards, however, since the chancellery is also the best-positioned government office to force action. It has regularly convened the digital cabinet to marshal interagency efforts and has injected input from external stakeholders into strategy and efforts to establish a digital state.

There has been some consolidation that could lead to an expanded BMDV becoming the incubator for a future all-encompassing digital ministry. The shift of the BMWK’s European and international digital policy units, and competent executive staff, to the BMDV could allow for a new digital czar to set policy on the international stage at the Internet Governance Forum (IGF), in the EU Digital Ministers Council in Brussels, and at other external gatherings. The BMDV also oversees telecommunications, broadband, and the Digital Services Act, and chairs the government’s digital cabinet with a €500 million embryonic budget.

Germany’s success in the ongoing effort to forge a digital strategy will depend on the BMDV’s ability to forge a “networked mentality” that can establish consensus within the federal government; among national, state, and local policymakers; and between the public and private sectors. And cooperation between the BMDV and BMWK will be particularly crucial for assembling consistent domestic and global strategies for data governance, startups, international standards, gaming, market access and market capture by techno-authoritarians, and industrial policies for the technology sector, including digital infrastructure, and internet governance.

Recommendations

Germany’s ability to pursue its strategic objectives and shape the global technology order requires all levels of government to alter their mindsets and engage in deeper interdisciplinarity. This will require a fundamental rethink in their operating systems. Seven recommendations for achieving this are:

Push a clearly articulated “rules-centric” doctrine of digital sovereignty rooted in freedom to choose, open markets, and human rights. Strategic ambiguity around the concept of digital sovereignty has outlived its purpose. As Europe operationalizes strategic technology projects and issues rules on AI, cloud computing, semiconductors, 5G/6G mobile networks, and quantum computing, the German government must shed an ambiguity that has become counterproductive.

Ensure ministry staff and digital policy units, especially at the expanded BMDV, think geopolitically. The BMDV should establish interagency meetings to assess the geopolitical implications of digital and technology regulation and policies. This requires boosting the AA’s and the BMVg’s role in technology policymaking. The German government should extend these ministries’ mandates to areas beyond 5G equipment, cyber norms, non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction (WMD), and EDT procurement. Their portfolios should include technology research and development, technical standards, and civilian vendors for infrastructure beyond mobile network equipment.

Draft a Comprehensive Technology and Foreign Policy Action Plan that links the Digital Strategy with the pending National Security Strategy. The BMDV, with the BMWK, BMBF, BMI, AA, and BMVg, in consultation with other stakeholders, drafted the first-ever integrated German digital strategy. The BMDV, AA, and BMWK should now draft an action plan that links domestic and European technology-industrial policy and regulation with foreign policy issues relevant to techno-authoritarianism, international standard-setting, internet governance, and technology alliances. The action plan must set budgetary priorities that guarantee Germany’s post-COVID-19 fiscal consolidation does not adversely affect a technological transformation that can meet the challenges of the next wave of global geopolitical and economic competition.

Establish the position of a technology ambassador-at-large with three senior deputies that can operationalize German digital technology and foreign policy. The AA should establish an ambassadorship-at-large, with state secretary rank, specifically to marshal the action plan. The structure under the ambassador-at-large should include deputies addressing cyber security, the digital economy, and digital rights who coordinate closely with other ministries to guarantee an able and cohesive international expression of Germany’s technology policy objectives.

Increase the agility of digital federalism. Germany must strengthen the interoperability, innovation complementarity, and technology-security assessments of federal and state (Bund and Länder) governments to build scalable technology on a European and, ultimately, global level. Domestic efforts in this area are, therefore, a foreign policy issue. Germany could, for example, support an “app store” for digital tools related to education, healthcare, and policing. The federal government could also strengthen conditionality among its funding incentives for technology procurement through cyber and vendor guidelines that align with national, EU, and NATO security concerns.

Establish a cross-committee, parliamentary Technology Foreign Policy Working Group. Such a body would ensure consistency in approaches to policy areas ranging from federalism to democratic technology alliances. The group, comprising key cross-party members of the Digital, Foreign Affairs, Economic, Interior, Finance, and Defense Committees, would focus on issues relevant to all represented portfolios.

This online text is the introduction to and summary of the DGAP Report "A Digital Grand Strategy for Germany". Download the full report here.

Chapters of the DGAP Report "A Digital Grand Strategy for Germany"

- The Geopolitics of Digital Technology Innovation

- Technology and Industrial Policy in an Age of Systemic Competition

- Germany’s Role in Europe’s Digital Regulatory Power

- Germany’s Economic Security and Technology

- Germany’s Global Technology Diplomacy

- Ethical and Operational: the German Military