Contrary to widespread concerns, GenAI played a limited role in South Africa's 2024 election disinformation landscape, with traditional sources and specifically engineered collective mobilization campaigns via social media remaining the primary drivers of misinformation—suggesting that existing media and social structures demonstrated resilience against AI-driven electoral manipulation.

This paper explores the role of Generative AI (GenAI) in South Africa’s 2024 General Election, focusing on evidence-based findings regarding the spread and influence of AI-generated disinformation. Using a framework of proxy indicators – including the proliferation of AI-generated disinformation, foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI), and shifts in public trust in government and media – the study provides a clear analysis of GenAI’s measurable impact on the election.

This text was first published by Friedrich-Naumann-Foundation. You can read the full Policy Paper by Phumzile Van Damme, Kyle Findlay and Aldu Cornelissen here.

Explore the Data

AI-Incidents

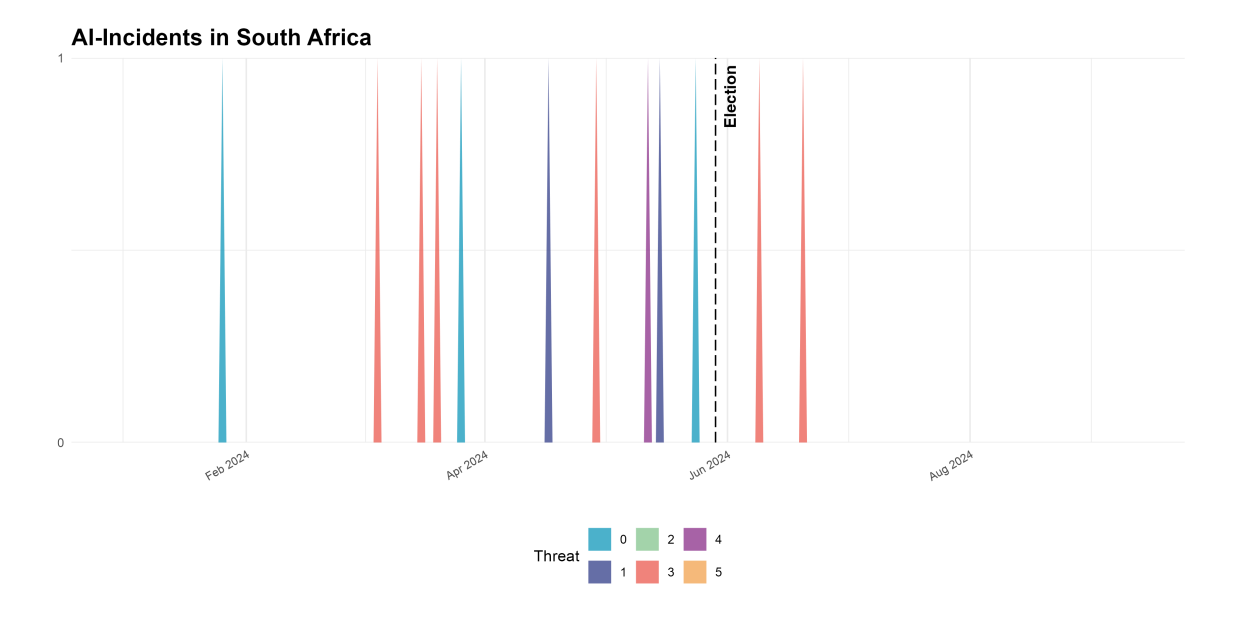

South Africa held its General Elections on May 29, 2024. The analysis of AI-related incidents, covering the period from January 1 to June 30, 2024, is based on 261 news articles and identified 12 distinct AI-related cases.

Trends:

- Limited use of AI in South Africa’s election

-

As shown in the analysis of AI incidents based on news articles above, there was no widespread adoption of AI, nor was there a single crucial instance of its use that had a significant impact on the election results. Instead, AI in the context of South Africa’s elections appeared to be more associated with humorous or experimental attempts to explore what might work to mobilize voters, rather than a widespread adoption or reliance on it for political campaigning.

- No Widespread Adoption of AI Due to the “Affordability Non-Adoption Cycle”

-

As highlighted in the Policy Brief research on the impact of AI in South Africa remains limited. This can be linked to an observed trend referred to as the “Affordability Non-Adoption Cycle” (p. 5), which demonstrates that the adoption of technology has been minimal due to high costs and limited access. Only recently has AI started to be adopted in the daily lives of SA citizens, for example with students increasingly using it. This trend has been quite recent and is thus still ongoing.

- Mis- and Disinformation Adapted to the South African Context

-

To ensure that misleading content is perceived and shared, in many contexts, a crucial element is its ability to appeal to emotions.

- Higher awareness of AI generated Disinformation by South Africans, compared to the global average

-

Based on Data by the Ipsos Global Views on AI and Disinformation it becomes evident that in comparison to the Global Average, South Africans show higher consciousness of disinformation connected to AI.

- Visibility strategies on social media platforms connected to the Influencer

-

Social Media platform “X” serves as a key venue for political discussion in South Africa. To gain visibility on this platform, many political candidates and parties employ strategies involving 'pseudo-anonymous influencers,' particularly those tied to the 'paid influencer industry.' In some cases, there also appears to be a potential connection to Russia, as exemplified by supposed collaboration with Jacob Zuma’s daughter, to gain visibility.

- Attacks on electoral integrity, intent to attack trust in electoral infrastructure

-

The political party MK, employed the tactic of deliberately spreading disinformation on the electoral process, to create a playing ground and rising skepticism for the time after the election results were announced. The South African Independent Electoral Commission (IEC) reacted to this and was able to “pre-bunk” this disinformation.

- Significant employment of “mega influencers”

-

The process of turning influence into a product that can be acquired by political parties and candidates with sufficient resources is referred to as the 'Commodification of Influence' (p.15). This practice, particularly involving “mega influencers”, was evident during the South African elections.

Proxy Variables:

- Trust in News

- Source of News

- Social Media Usage

- Trust in Media and Government

Vulnerabilities:

- Uneven distribution of AI and access to technology can drive vulnerability of manipulation

-

While the Policy Brief of South Africa states that AI can drive economic development in various fields, it also points towards the inequality it can enhance with only parts of the population having access to the technology. Next to this, it is pointed out that AI can reinforce inequality by AI based on “ethical issues such as data privacy and algorithmic bias”. This not only results in unequal adoption but with parts of the population not having access to dependable resources to inform themselves, leaving them especially vulnerable to manipulation

- As AI advances, so does its risks

-

While there has not yet been an AI-generated ‘bombshell’ that can be argued to have influenced South Africa’s 2024 elections, the country remains vulnerable, particularly when considering the future. The analysis suggests that AI technology has not yet been adopted on a large scale. However, as its quality improves, its application becomes easier, and experiences accumulate from other major elections that have occurred or will occur in the coming year, the likelihood of its use in elections increases. This includes both positive applications and negative impacts, such as fueling large-scale disinformation campaigns, which pose a significant vulnerability to the country.

- What's App, One-on-one communication

-

As depicted in the "Visual on Social Media Usage," the most used platform in South Africa for any purpose is WhatsApp, with 84% of the population using it, according to the Digital News Report (2024). The Policy Brief of South Africa highlights that this widespread usage poses a significant vulnerability and potential for the spread of misinformation and disinformation. As AI technology improves and adoption increases, this could accelerate the spread of such content via one-on-one communication platforms.

An additional challenge related to this form of online communication and its potential connection to AI usage is that researchers currently have no way to study this. This issue is also evident in the analysis of the AI-Democracy Initiative. While filtering newspaper articles for relevant AI incidents provides insight into AI's impact on elections, it cannot account for AI-generated audio, pictures, videos, or text in private one-on-one conversations, which could be persuasive and impactful. Overall, no fact-checking or analysis of such communication is possible, making it very difficult to determine its impact and secure this space from misinformation and disinformation.