| Regardless of Donald Trump’s threats and frustration over the unwillingness of European members of NATO to pay and supposedly ungrateful Ukrainians, it is unlikely that the US president would withdraw the American nuclear umbrella from Europe. Doing so would harm the United States itself and weaken America’s defense industry. |

| Nevertheless, to be prepared in case the United States does diminish its nuclear protection, nuclear cooperation between Europe’s two nuclear powers, France and the UK, should be intensified. |

| Furthermore, the exchange between nuclear and non-nuclear European countries should be strengthened. Because NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group has been an example of successful cooperation in this regard for decades, it should serve as a model. |

Even before the 2024 US presidential elections, there was a brief public debate in Germany about the reliability of the American nuclear umbrella that gave rise to several odd hypotheticals. There was talk of a European “red button” that would be passed through the capitals of the EU, or of 1,000 nuclear warheads that Germany could buy from the United States in order to become a nuclear power.

Now that Donald Trump appears to be demonstratively siding with Russia after just a few weeks in office, thereby breaking with the foundations of transatlantic security relations, the question of the credibility of US nuclear protection for European allies is being raised once again and more intensely. What happens if the United States revokes its long-standing nuclear security pledge within NATO and ends the system of “extended deterrence”? How can Europe maintain a nuclear deterrent against an aggressive and revanchist Russia and what steps need to be taken?

The Likelihood that the Nuclear Umbrella Will Be Closed

The main question is: how likely is it that Washington will withdraw the existing nuclear security pledge for non-nuclear allies? In his first term in office, President Trump presented himself as a strong supporter of nuclear deterrence, and the Nuclear Posture Review adopted under his aegis clearly acknowledged the American nuclear alliance pledge. There is also still a broad bipartisan consensus in the United States on the need for nuclear weapons and extended nuclear deterrence. It stems from the realization that, without the ability to deter Russia and China, the US would lose its superpower status. In October 2023, the bipartisan Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States presented its final report in which Republicans and Democrats unanimously committed to nuclear deterrence and called for new nuclear capabilities for a credible deterrent in Europe and the Indo-Pacific.

Given the volatility of the current US president and his new pro-Russian orientation, such determinations may no longer be of significance. Nevertheless, there are some factors that the president is probably not aware of – but that the security establishment in the United States is – that speak in favor of maintaining “extended deterrence”.

There is still a broad bipartisan consensus in the United States on the need for extended nuclear deterrence.

The nuclear umbrella that the United States spread over its allies was always an instrument of nuclear non-proliferation. The US nuclear pledge has prevented other European or Asian states from seeking their own nuclear weapons. If the credibility of this umbrella were to be destroyed in Europe, this would also have an impact on US allies in Asia. Countries such as South Korea, Japan, or Australia could develop their own nuclear weapons to secure their deterrent capability against China or North Korea. Washington has always tried to prevent such a proliferation of new nuclear powers. In addition, the Trump administration is likely to attach particular importance to allies in the Asia-Pacific region if China is seen as the main adversary.

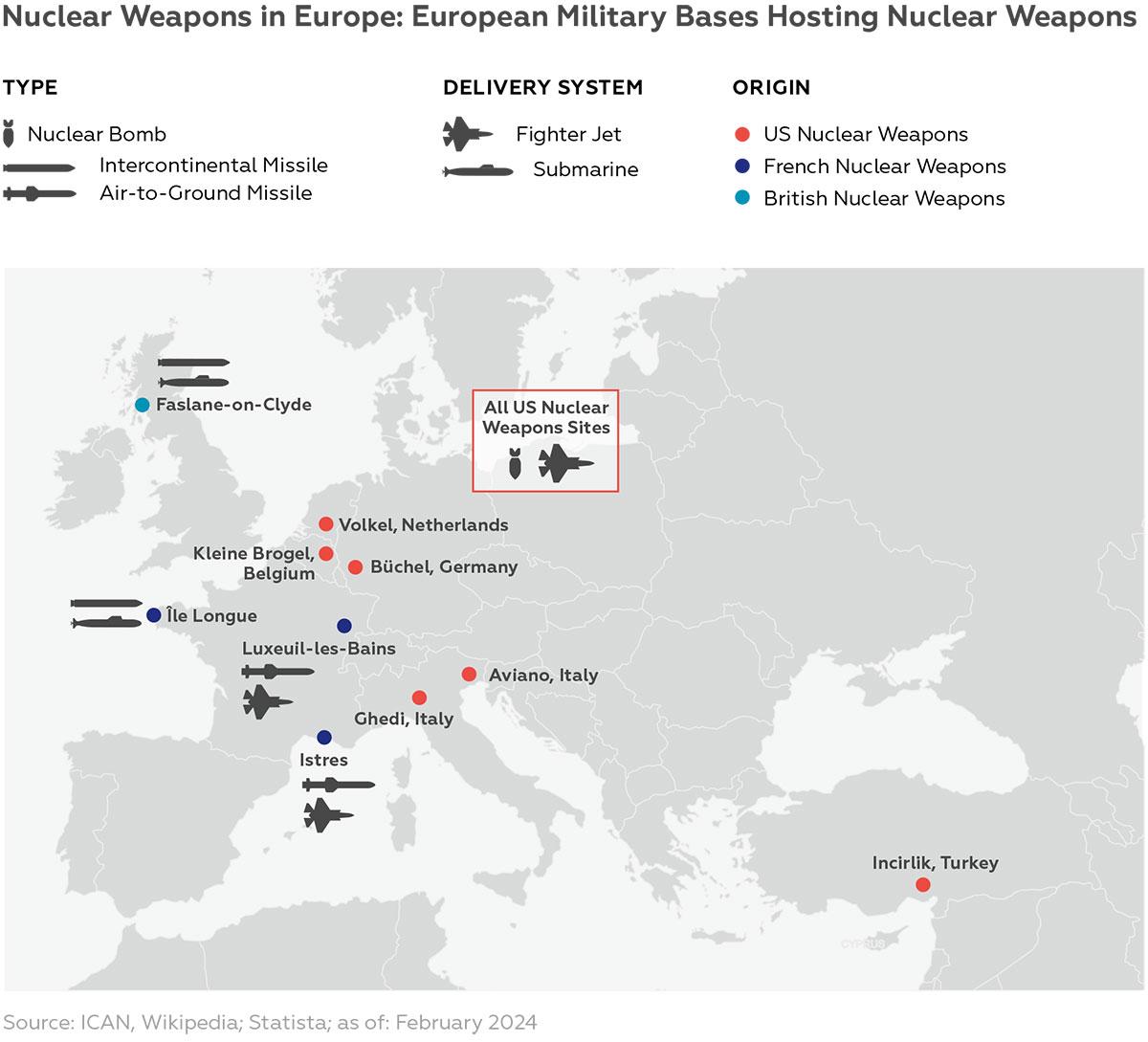

NATO’s nuclear deterrent – i.e., the American nuclear bombs for European carrier systems stationed in Europe as part of “nuclear sharing” – is currently being strengthened. The B61 nuclear bombs stored in Germany, Belgium, Italy, and the Netherlands are being replaced by a new, modernized version, the B61-12. In addition, all these countries have procured the American F-35 fighter aircraft as a carrier system. Germany will receive the first of the 35 F-35 fighter bombers it ordered in 2026. In addition, the US weapons depots in Europe, such as the German nuclear base in Büchel, are currently being modernized to accommodate the new types of weapons.

In the UK, which has not had American nuclear bombs on its own territory since 2008, the United States is currently preparing to be able to deploy the B61-12. At the former Lakenheath nuclear base, the remaining US storage facilities are being modernized and made ready to receive the bombs. At present, it is not publicly known whether American nuclear weapons will be stationed there permanently or whether Lakenheath will merely serve as an alternative site in addition to the continental European storage facilities. In any case, the establishment of a further nuclear weapons base in Northern Europe actually means a strengthening of NATO’s nuclear credibility.

Irrespective of Donald Trump’s annoyance at NATO, Europeans who are unwilling to pay, and supposedly ungrateful Ukrainians, the US deterrent within the framework of NATO currently appears to be stable. Any deviation from this would damage the United States itself and weaken the American arms industry, for example through less demand for F-35s.

Hope Is Not a Strategy – Thinking Through the Worst-Case Scenario

Regardless of the factors mentioned above, it cannot be ruled out that Donald Trump, despite all his own interests, will cancel the American commitment to NATO and thus also the nuclear protection for Europe. How could Europe act in such an extreme situation?

Two options that have occasionally been raised in Germany are likely to be ruled out. Contrary to the suggestion of a few eccentric academics and far-right politicians, Germany will not develop its own nuclear weapons. In both the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) and the Two-Plus-Four Treaty on German Unity, the Federal Republic of Germany has committed itself to not seek its own nuclear weapons. There is no democratic political force in Germany that would seriously undermine this commitment. Furthermore, the development of a nuclear weapons capability, including delivery systems, would swallow up huge sums of money that are completely disproportionate to any possible benefit – not to mention the political signals that would be sent out by a German grab for the bomb.

The idea of a European nuclear capability within the framework of the European Union is also unrealistic. The EU does not have a common government whose president or prime minister could decide on the use of nuclear weapons. Having to agree on a nuclear response to a vital threat after hours of late-night meetings in Brussels – possibly even as a majority decision – is illusory and would have no deterrent effect whatsoever.

In the same breath, the idea has often been formulated that France could act as a nuclear guarantor for the EU now that the UK is no longer available due to its withdrawal from the Union. What speaks against this, however, is the fact that Paris has always rejected the idea of “extended deterrence,” i.e., that a nuclear state could provide nuclear security guarantees for a non-nuclear ally. For France, nuclear weapons were always national weapons that could only protect its own territory. This is why France developed its own nuclear potential instead of relying on the US umbrella.

If alternatives to the worst-case scenario of an end to American nuclear protection are to be discussed, this cannot take place at either the national level or within the European Union itself. Such discussions must include the second European nuclear power, Great Britain, as well as militarily and geopolitically significant states such as Norway. Thus, a nuclear deterrent without the United States – albeit limited – can only be considered within the framework of the European pillar of NATO.

The Nuclear Weapons of France and Great Britain

NATO’s two European nuclear members, the UK and France, have contributed to NATO’s overall deterrent from the outset. Since the Ottawa Declaration in 1974, NATO has always emphasized that its deterrent effect stems from the fact that the Alliance confronts a potential aggressor with two other independent nuclear decision-making centers whose possible reactions must be included in any risk calculation.

The UK has around 225 nuclear warheads, of which a maximum of 120 are said to be operational. They are based on an American warhead design and are carried on American Trident missiles that would be launched from submarines. One of the four British nuclear submarines is always at sea and thus guarantees a permanent deterrent capability (CASD – Continuous At Sea Deterrent). From the beginning, London placed its nuclear power within the NATO framework and thus implicitly made a nuclear pledge to the other members of the Alliance. However, despite its close ties to the US nuclear complex, the UK has developed its own targeting and reserves the right to use its nuclear weapons independently if “supreme national interests” are affected.

France has around 290 nuclear warheads that can be used by both aircraft and submarines. Paris has always attached great importance to the complete independence of its deterrent force. Although it has accepted American help with missile technology, it has developed the nuclear components itself. This means that the French nuclear potential is strictly outside NATO structures. Paris does not take part in meetings of the Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) in which nuclear and non-nuclear NATO states exchange information.

Since the 1990s, France has made several offers to Germany for nuclear dialogue. In 1995, President Jaques Chirac spoke of a “concerted deterrence” that he wanted to form with Germany within the framework of the European Union. All German chancellors since Helmut Kohl have met such offers with skepticism because they always suspected an anti-American bias and did not want to send misleading signals to Washington. France had also never made a nuclear security pledge comparable to the American one because it considered “extended deterrence” to be fundamentally untrustworthy.

However, because of current US policy, there are now signs of a Zeitenwende – a sea change – in French nuclear thinking. In 2020, President Emanuel Macron had only offered European partners a rather vague nuclear strategic dialogue to promote the “strategic culture” in Europe. In 2025, he went beyond all previous French offers. In his speech to the nation on March 5, Macron declared his intention to open a strategic debate on the protection of allies on the European continent through the French nuclear deterrent. Although this declaration is still a long way from a nuclear “commitment,” it breaks with what had been a core element of French nuclear doctrine that is summarized in the phrase la nucléaire ne se partage pas – “nuclear cannot be divided.” This suggests new possibilities for a European nuclear deterrent.

If the United States were to fail as a nuclear protective power, NATO Europe would have a nuclear deterrent potential of around 500 warheads. This would have a certain credibility simply because France and the UK are geographically closer to the Russian threat than America.

But would these rather small arsenals really be enough to deter Russia, the world’s second-largest nuclear power? As the question of “How much is enough?” cannot be answered in advance, nobody knows. However, despite all the technical and mathematical calculations about the number, size, or orientation of nuclear weapons, nuclear deterrence is – above all – a political concept aimed at the cost-benefit calculation of the attacker. In the event of a possible attack on Poland or the Baltic states, could Moscow be sure that London and Paris would not react with nuclear weapons? If they miscalculate, the damage for Russia would be so enormous that any hoped-for “benefit” of the attack would be far exceeded. This was always France’s justification for maintaining its comparatively small nuclear arsenal during the Cold War. In Paris, it was said that it would not be possible to kill the bear, but it would be possible to tear off one of its paws. The knowledge of this danger would deter Moscow from reckless aggression.

Does this mean that American nuclear protection could easily be offset? Of course not. However, without it, deterrence in Europe against Russia would not disappear completely. Its credibility can be considerably strengthened by demonstrating European resolve and determination toward Russia. This applies to the two European nuclear states as well as to their non-nuclear NATO partners.

European Nuclear Cooperation

Despite their serious differences in nuclear strategy, France and the UK have been exchanging ideas since the early 1990s within the framework of the Joint Nuclear Commission. In October 1995, both countries declared the close alignment of their vital interests in the “Chequers Declaration,” and in November 2010, the British-French cooperation was formulated in the Lancaster House Treaties. As neither partner was willing to permit insights into the secret areas of nuclear doctrine or targeting at that time, these agreements were primarily concerned with technical cooperation and joint research.

After a promising start to cooperation, the turmoil surrounding the UK’s withdrawal from the EU – and, later, French anger at AUKUS, the trilateral security partnership of Australia, the UK, and the US – made nuclear cooperation between the two countries more difficult. With Russia’s attack on Ukraine, contacts have reintensified significantly.

In the meantime, both countries have extended nuclear exchanges to other European NATO members. Since Russia’s large-scale invasion of Ukraine, France has cautiously opened its previously purely French nuclear exercise “Operation Poker” to European allies. In April 2023, Paris invited NATO ambassadors to the French nuclear weapons base Ile Longue for the first time. In October 2024, Germany and the UK signed a defense policy cooperation agreement in which talks on nuclear issues were explicitly mentioned.

The latest developments in the United States have given new urgency to the issue of close security cooperation between NATO and Europe, including in the nuclear field. During Donald Trump’s first term in office, individual NATO states attempted to forge bilateral security agreements with the US by demonstrating good behavior. However, following President Trump’s grotesque reversal of blame that branded Ukraine as an aggressor, this is no longer possible, especially for Eastern Europeans. Accordingly, the EU and members of NATO (not counting the US) are currently presenting themselves as remarkably united.

For a European Nuclear Planning Group

To be prepared for the eventuality of a decline in American nuclear protection, nuclear cooperation between the two European nuclear powers should first be intensified. Paris will not want to give up its nuclear independence, nor will London want to abandon its special nuclear relationship with the United States. Within these limits, however, France and the UK could move much closer together and begin an exchange on such sensitive issues as nuclear deployment principles. Such a trusting exchange would convey an image of unity and strengthen deterrence overall. In addition, the exchange between nuclear and non-nuclear Europeans should be strengthened. NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group has provided a positive example of this for decades.

At the beginning of the nuclear age, the United States treated nuclear issues extremely restrictively and left its NATO allies largely in the dark. The more American nuclear weapons were stationed in Europe, the more urgently the Europeans expressed their desire for information and participation. They were not trying to make or participate in decisions on nuclear weapons deployments, but – because they would have been most affected by the consequences – they wished to learn about numbers or deployment scenarios. Thus, the Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) was founded in 1966 for the purpose of exchanging information. In this forum, the United States discussed nuclear issues with its NATO allies (except France). This included such important aspects as nuclear targeting or whether and how allies should be consulted before a nuclear weapon was used.

In the following years, non-nuclear states were even actively involved in possible nuclear operations. Under the acronym SNOWCAT (Support for Nuclear Operations With Conventional Air Tactics), which was recently renamed CSNO (Conventional Support for Nuclear Operations), non-nuclear states would provide conventional support, including aerial refueling, reconnaissance, and the suppression of enemy air defenses. Corresponding scenarios have been and continue to be played out in regular nuclear exercises such as Steadfast Noon.

If the United States were to withdraw from the NATO nuclear deterrent alliance, the European members of NATO could build on their experience in the NPG. France and the UK would, depending on their own assessment, share nuclear-related information with allies wishing to participate in such a process. As in the NPG, the aim is not to make joint decisions, but to share information and possibly common positions on fundamental issues of deterrence, which, in turn, would convey an image of unity.

Accordingly, the CSNO model could be transferred. France and the UK would receive conventional support from their allies in the event of possible nuclear weapons deployments and demonstrate this in regular exercises – also as a deterrent signal to Russia.

In a further step, France could regularly fly to allied bases with its nuclear-capable Rafale carrier aircraft. Although this would not be comparable to the US stationing of nuclear weapons on European soil, it would also send a political signal of deterrence to Moscow. Whether France could ever decide to station its own nuclear weapons outside French territory is currently not foreseeable.

All these considerations only apply in the unlikely event that the United States really does withdraw from NATO and its nuclear deterrent alliance. As long as this does not happen, NATO will remain the core of nuclear deterrence in Europe. However, these considerations show that NATO Europe would not be left without a deterrent capability even in this extreme situation. To be prepared for such an eventuality, consultations among France, the UK, and the non-nuclear allies should be initiated as soon as possible.