Please note: Below you will find an executive summary and the introduction contained in the report by Digital Power China (DPC), a research consortium convened by DGAP Research Fellow Dr. Tim Rühlig. The complete report can be downloaded as a PDF here.

Executive Summary: Getting China’s digital technology policy right: implications for the EU

For decades, Europeans have considered the People’s Republic of China (PRC) incapable of ground-breaking innovation. Only recently, in the middle of the digital transformation, have we found that dependence on China is not limited to critical raw materials, and that the Chinese contribution to supply chains is not limited to cheap labour. China is striving for technological leadership in a broad range of emerging and foundational technologies.

Growing geopolitical tensions have heightened the awareness that critical dependencies can be weaponized for political purposes. Russia is leveraging European dependency on fossil fuels in its war against Ukraine. The PRC’s economic coercion against Lithuania leaves little doubt that China stands ready to blackmail Europe when it considers that its core interests are at stake. US willingness to act unilaterally regarding China and to exert pressure on the EU and its member states to cooperate is also now a pressing issue for policymakers.

In the light of such deep dependencies and their weaponization, the European Union (EU) is attempting to manage its capacities and its dependencies on China. It defines this as Open Strategic Autonomy, where the goal is to uphold the EU’s capability to act internationally without being constrained by technological dependencies.

The EU has started to identify critical dependencies but what reads well in the abstract is difficult to operationalize. Despite the European Commission’s lead, EU actors are still trying to address divergent challenges, and therefore advocating divergent sets of tools, to achieve Open Strategic Autonomy. For example, the extent to which the EU should strive to “re-shore” the production of emerging and foundational technologies or instead aim to diversify its supply chains is a matter of controversy.

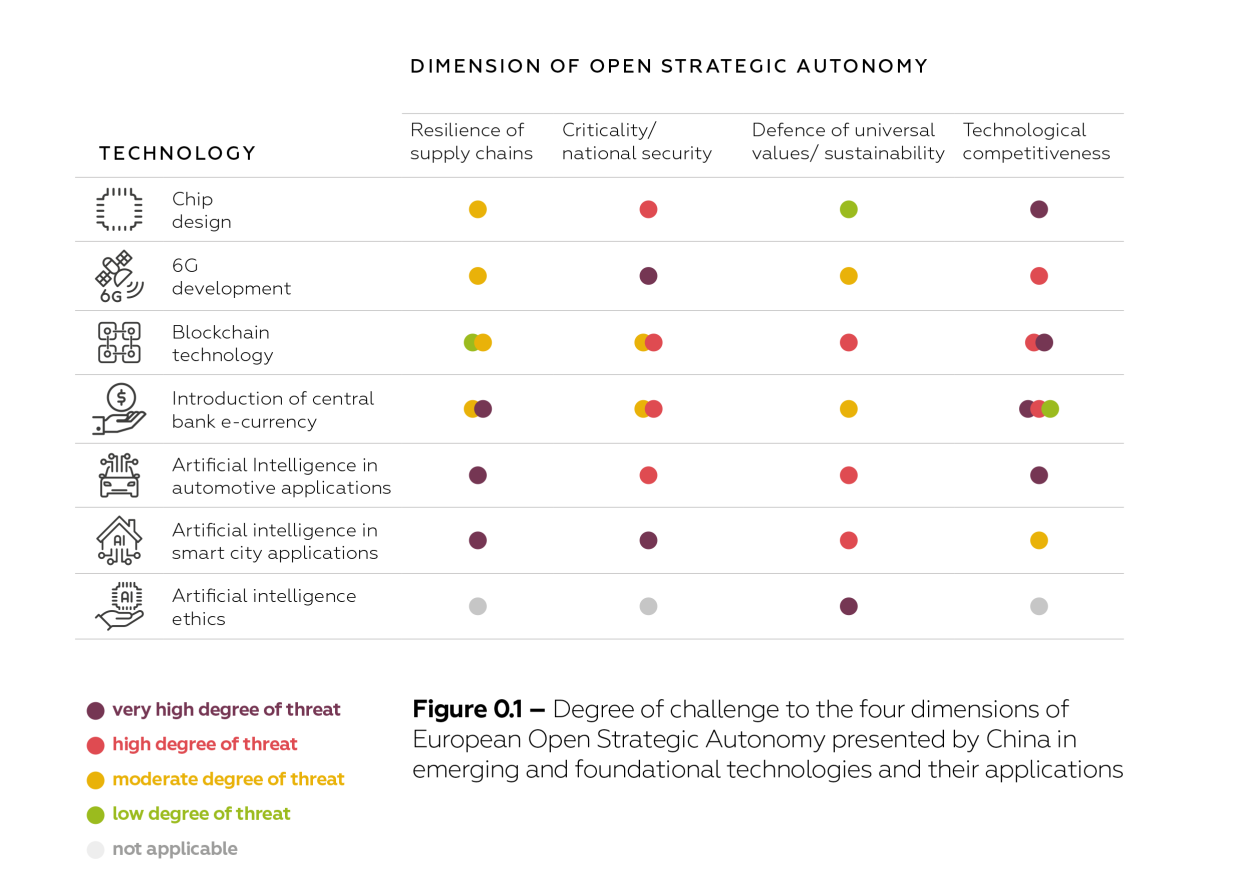

This report operationalizes Open Strategic Autonomy by identifying four dimensions:

- resilience of supply chains, or the robustness of the supply of critical materials and primary products in case of major disruption ranging from natural disasters to a pandemic or war;

- criticality/national security, or the security of IT, networks and cyberspace that are crucial not only for military defence, but also to the functioning of increasingly interconnected societies and economies;

- defence of values and sustainability, or the protection of basic human rights in the digital age, primarily in Europebut also around the globe, as well as the prioritization of sustainability goals not least for the sake of combating climate change; and

- technological competitiveness, or boosting Europe’s own technological capabilities in terms of research, innovation and development, as well as advanced manufacturing.

All four dimensions of Open Strategic Autonomy are not necessarily of concern to the EU in every emerging and foundational technology. Even where they are, the severity and urgency of the challenges posed by China vary. Operationalization in four dimensions does not make Open Strategic Autonomy less complex, but it does help to identify weaknesses that the European Union should strive to address in its attempt to gain such autonomy in anygiven foundational or emerging technology.

In its analysis of several emerging and foundational technologies, this report assesses the degree to which the four dimensions of Europe’s Open Strategic Autonomy are threatened by the PRC. Figure 0.1 illustrates that the challenges vary greatly across emerging and foundational technologies and their applications. Several notifications in one box indicate divergent risks that require divergent assessment within one dimension.

While it is difficult to compare the degree of risk across several emerging and foundational technologies, ranking within a single technology is easier. Hence, the assessment across technologies summarized in Figure 0.1 needs to be taken with a pinch of salt, and the overview clearly demonstrates that there is no clearly defined ranking of concerns across technologies. For example, it is not the case that national security is the primary concern regardless of technology or that values-related issues are necessarily the least urgent to address. Instead, the priority of threats to Europe’s Open Strategic Autonomy varies across the emerging and foundational technologies analysed in this study.

This risk assessment is based on rigorous research carried out by pairs of researchers that combine technical and China expertise as part of the Digital Power China (DPC) research consortium. Detailed discussion of the findings is available in this study alongside a separate chapter on the divergent approaches to Artificial Intelligence ethics in Europe and China.

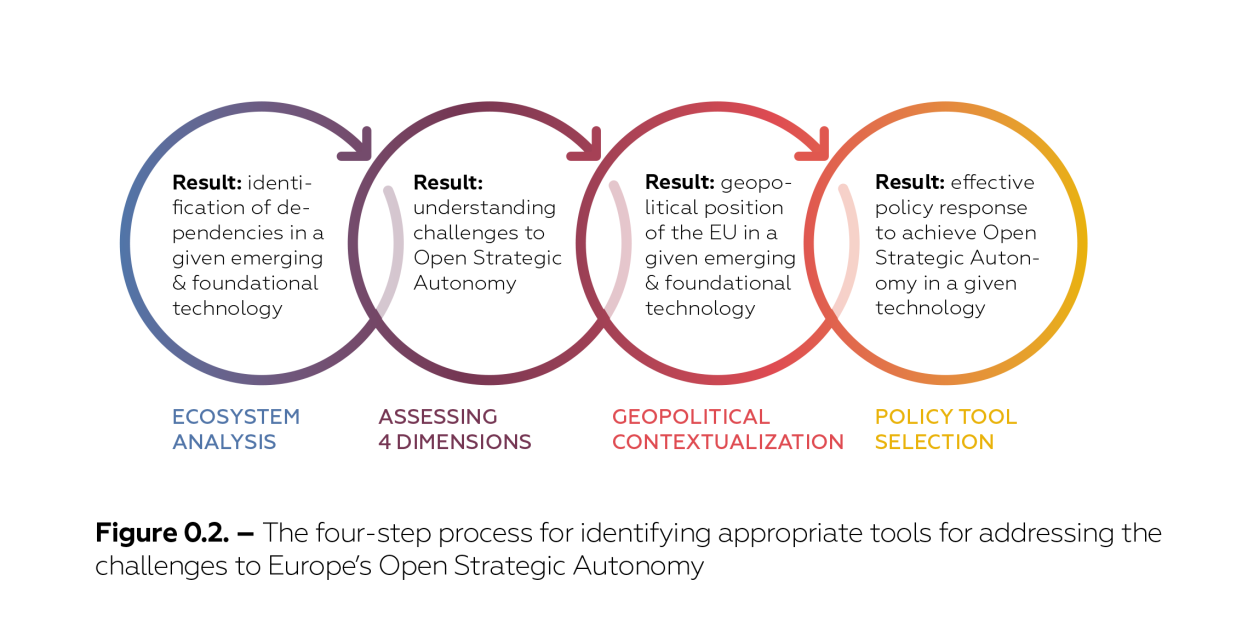

For European policymaking, this means that one-size-fits-all solutions are doomed to fail. For example, a policy instrument that might be useful for increasing European technological competitiveness in a given emerging technology is of no use in protecting national security concerns in that or another emerging technology. In some cases, tensions exist between the different dimensions of Open Strategic Autonomy within the same foundational or emerging technology. For example, the mitigation of national security risks in 6G is all about the trustworthiness of Chinese technologies and vendors, and requires thinking about precautions. Given China’s technological advances, however, Europe may not be able to maintain its technological competitiveness unless it continues to cooperate with the PRC. To strike a balance between competing policy goals is not impossible but requires a rigorous process. The introductory chapter of this study introduces a four-step process that helps to identify the challenges to the EU’s Open Strategic Autonomy across four dimensions and adequate policy tools.

Figure 0.2 summarizes how policymaking must start from an analysis of technological ecosystems to assess the degree of dependency and associated risks based on the criticality of the items under consideration, options for supply substitution and the extent to which dependencies are mutual, which limits the options for the PRC to weaponize European dependencies. Such analyses of technological ecosystems should be followed by an assessment of the implications for the four dimensions of Europe’s Open Strategic Autonomy.

Since no two dependencies carry similar risks, a geopolitical contextualization that considers geopolitical factors, such as regime type and the existence or absence of security alliances, is essential. The severity of dependencies and likelihood of their weaponization by China against Europe is decisive in determining the level of risk. This analysis also includes an element of foresight since truly strategic policymaking should involve a certain degree of anticipation. Knowledge of the actors that drive policy and technological development in the PRC is necessary but not sufficient for anticipating future developments in China. For this purpose, all the chapters in this study provide an overview of the most relevant actors in the PRC that European policymakers should be carefully monitoring. Each chapter provides a brief list of actors, an actor description, including of their role in the Chinese system, and a rough indication of their relevance to European foresight exercises in the respective case studies.

Finally, European policymakers should use different policy tools to achieve clearly defined goals based on political priorities and depending on which of the four dimensions of European Open Strategic Autonomy is affected.

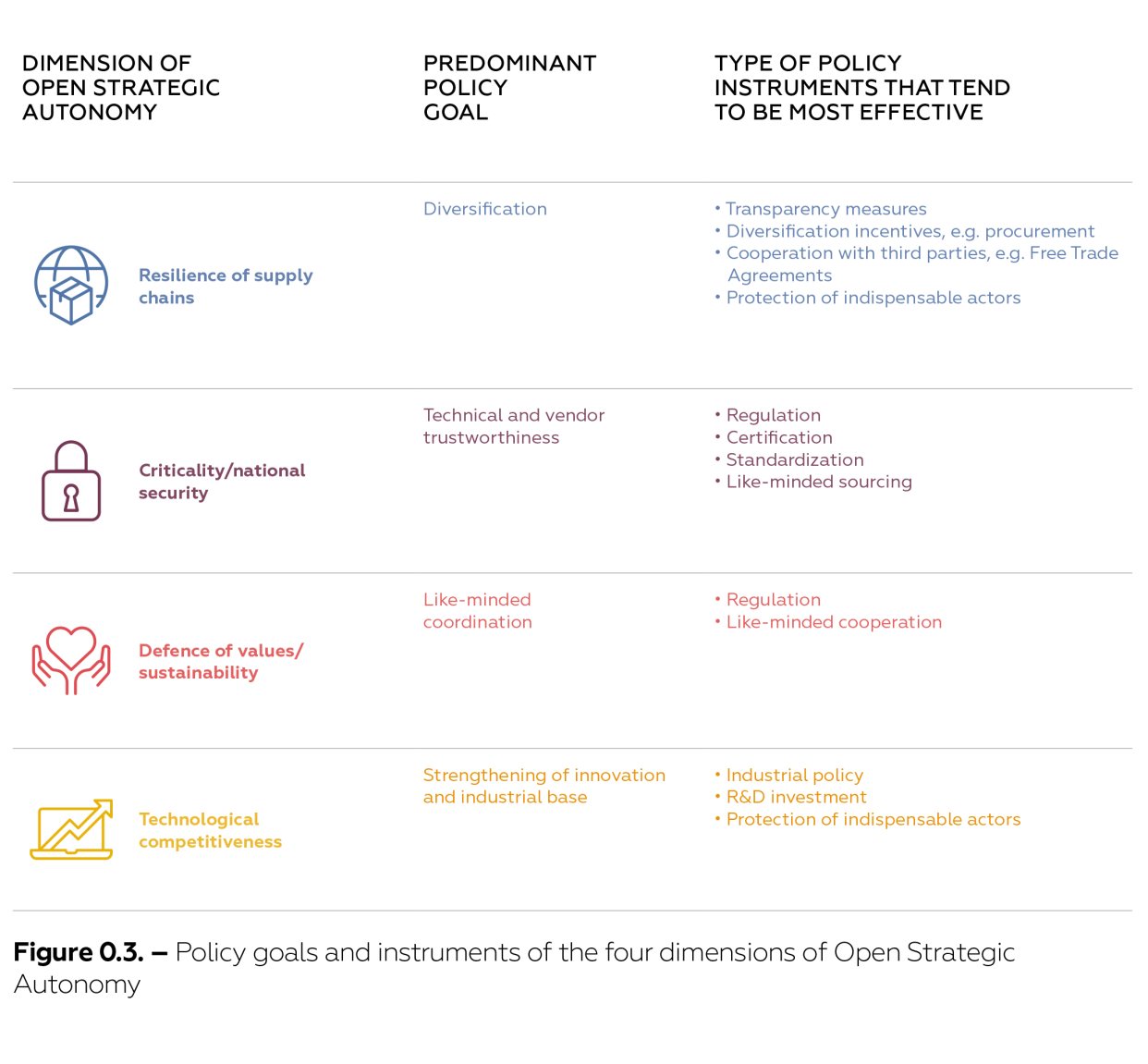

Appropriate policy tools differ not only depending on the four dimensions of Open Strategic Autonomy, but also across emerging and foundational technologies and their applications. However, based on the limited number of cases investigated in this study, we find that – by trend – certain types of policy tools seem to be particularly suited to addressing one or other of the four dimensions of Open Strategic Autonomy. Figure 0.3 summarizes the predominant goals to be achieved in the four dimensions and the types of policy instruments that tend to be identified as most effective.

Watch the Digital Power China Podcast Discussions:

About the Digital Power China Research Consortium

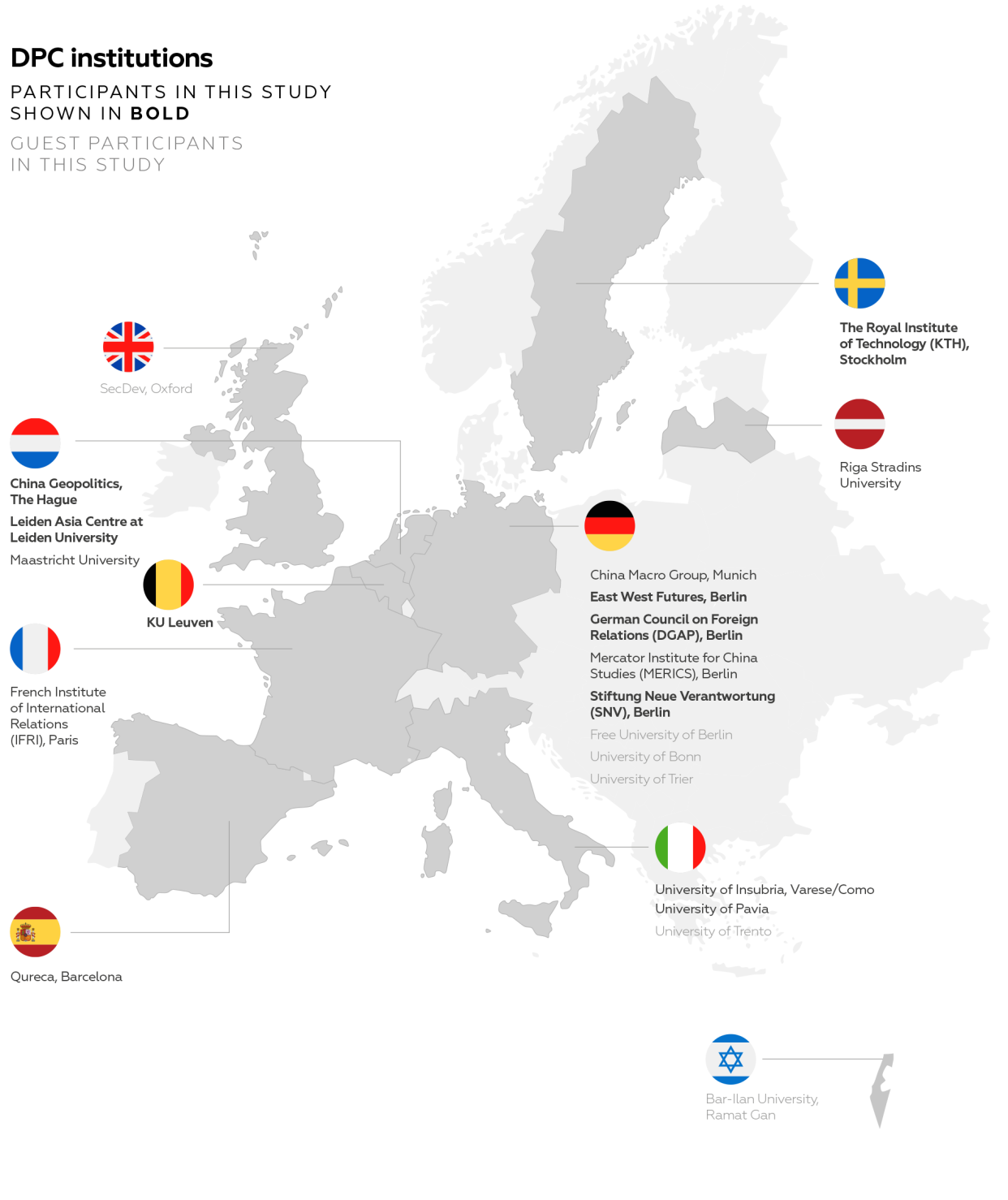

The Digital Power China (DPC) research consortium is a gathering of China experts and engineers based in eight European research institutions, universities, think tanks and consultancies. Not all DPC researchers contribute to every report. For this report, DPC has been joined by invited guest researchers.

The group is devoted to tracking and analysing China’s growing footprint in digital technologies, and the implications for the European Union. DPC offers the EU concrete policy advice based on interdisciplinary research. Tim Rühlig, Senior Research Fellow at the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP), is the convenor of DPC and co-chairs the initiative with Carlo Fischione, a Professor at the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm.

DPC systematically pairs technological and country expertise, which is based on rigorous academic research combined with experience of the provision of policy advice. The informal group brings together a variety of European researchers in order to combine diverging perspectives from across the continent. Responsibility for the accuracy of the views expressed remains solely with the indicated authors. This report has been generously funded by the German Foreign Office.