|

Introduction |

Please note the online version of this report doesn't contain footnotes. To view the footnotes, please download the PDF version here.

Key Findings

Geostrategic Landscape: Assessing Political Change in Europe

1 – Russia’s war against Ukraine has exposed the existence of not one single Europe, but several. Governments are reacting differently in the areas of threat perception, alliance policy, defense budgets, or arms deliveries to Ukraine. Changes are taking place at different speeds, to different extents, and with different political orientations. This could point to possible fault lines underlying the unity Europe currently demonstrates. Also, as the war drags on, governments may find it increasingly difficult to maintain public support for the compromises needed to maintain unity. Divisions could become more likely. Therefore, the war also serves a test case for the alliance’s ability to maintain cohesion in the event of a future conflict that would directly involve NATO.

2 –Many European states saw the confrontation with Russia coming. Strategic documents from Eastern European countries, but also France and the UK, described Russia as a potential aggressor, even if they did not explicitly mention the possibility of war. But this awareness has not led to similar policies toward defense, Russia, and Ukraine in different parts of Europe. Not all Europeans see Russia as an existential threat to themselves or to Europe. Most would probably agree that Russia is at least not the only threat to Europe.

3 – The policy changes in European countries vary from fundamental changes to their strategic documents to adaptation in budgets. For some governments, the war has meant a reordering of priorities – their strategic documents had not foreseen the Russian aggression and could not be used for guidance in coping with the new reality. Others saw their expectation of a negative and aggressive role of Russia confirmed – meaning their strategic documents proved valid after the military escalation in February 2022. Many countries made changes as part of their annual policy cycle, for instance as regards budget changes. Germany, Sweden, and Finland have taken significant decisions involving fundamental policy shifts beyond the budget cycle.

4 – There is also a global perspective on the impact of the war in Ukraine, and it is often about China’s role as Russia’s partner or as a security actor. The Russian war has opened the eyes of some European governments to the reality of geostrategic competition (Spain, Italy, UK, France, Finland, Germany). China as a strategic rival has gained attention, and governments are discussing taking up a more confrontational stance toward China. This is the case for Germany and Spain. Other European countries such as the UK, France, and Finland already acknowledged the challenge posed by China in earlier strategic documents. The outbreak of the war in February 2022 did not force them to reassess their position, as they were already aware of the security implications of China’s rise to global power.

Group 1: Shaken out of Obliviousness

Italy, Spain, Finland, Germany

This first group consists of countries that used to be largely oblivious to the threat that Russia poses to European security. For some, this reflected geographic distance. Both Spain and Italy paid more attention to security threats in their southern periphery, focusing on crisis management rather than on conventional territorial defense. Both countries have experienced wake-up calls. Spain went through a drastic shift in its threat perception and now clearly identifies Russia as the main threat. Italy has pledged to strengthen its support to NATO’s eastern flank, and both countries have made new commitments regarding defense spending.

Finland did not underestimate the Russian threat per se. It has always identified its eastern neighbor as the most immediate threat to its security. However, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine changed the security environment so dramatically that Finland overturned its long-standing policy of non-alignment and applied for NATO membership.

Germany is the most extreme case of a country in which the perception of the security environment is fundamentally changing. The Russian war has not only destroyed the European security order but almost all German mainstream assumptions about security and peace and about partnership with Russia. In fact, it took the Russian war, which, for the first time, confronted Germany with the new reality of insecurity in Europe, to get Germany to accept the relevance of geostrategy. This was acknowledged by the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz in his now famous „Zeitenwende” (tidal change) speech in February 2022.

Group 2: Seeing One’s Fears Confirmed

UK, Estonia, Lithuania, France, Norway, Romania, Poland

A second group of states sees the escalation in Ukraine as a confirmation of their threat assessment. France, the UK, and Norway have adjusted their threat assessment following the Russian annexation of the Crimean Peninsula in 2014 and have re-prioritized their response to Russia. Poland, Estonia, and Lithuania have consistently highlighted the Russian threat to their security due to their shared border with Russia and their history of having been part of the Soviet sphere of influence.

Group 3: Unconvinced by the Russian Threat

Hungary, Bulgaria

Both Hungary and Bulgaria have officially condemned the Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, both maintain a somewhat ambivalent position. Hungary still hopes for a return to the status quo ante, a position that can partly be explained by the country’s continuing energy dependence on Russia. Bulgaria, on the other hand, is caught in a protracted internal political crisis with changing governments. As a result, its position on the Russian invasion is not coherent. Beyond practical considerations, however, both countries share the perception that Russia, while to be taken seriously, is not a real threat to their security and the security of Europe in general.

Group 4: Focused on Conflicts Elsewhere

Greece, Turkey

Greece is clearly more concerned about Turkey as a security threat than Russia. At the same time, Greek governments have never ruled out the possibility of large-scale conventional war in Europe. Therefore, Greece feels that is better prepared for the new age of European defense than other European countries.

Turkey takes a balanced approach toward Russia, cooperating where possible but pursuing a strategy of „contained confrontation” where their interests conflict. In general, Turkey seems more concerned with threats on its periphery, including its strategic rivalry with Greece.

5 – Domestic audiences are an important factor for governments that see Russia as a threat and wish to shape their defense policy accordingly. However, this is a double-edged sword: In the case of Hungary, the government made use of the war to emphasize the scope of its bargaining power to obtain lower energy prices. In Spain, the evolution of the public discourse made it possible for the government to reposition itself toward greater support for territorial defense and Atlanticism. In other cases, for instance in Germany and Italy, the public discourse fluctuates between positions such as seeking to establish security with Russia or security against Russia. For France, the UK, but also for Turkey or Greece, the role of domestic politics is unclear.

Politico-Military Order

6 – The way Europe organizes its security no longerfits the purpose: There have been frequent calls for improving the division of labor between the EU and NATO in the past. Yet even with better arrangements between the two, it is unlikely that all the relevant needs that have become apparent through the current war can be covered. Neither the EU nor NATO offer an effective institutional framework for industrial cooperation, and the existing frameworks are difficult to join. Non-military decisions which nevertheless affect security, such as infrastructure, technology, or cyber policies, are taken solely by EU institutions. NATO as an institution or European countries outside of the EU have no direct influence on the EU’s decision-making, even if it affects them.

7 – NATO is receiving increased attention as the main defense institution that European states rely on. For the countries on NATO’s eastern flank, the effective implementation of the alliance’s new strategic concept, adopted at the 2022 NATO summit in Madrid (which includes a New Force Model, a strengthened regional focus, and deterrence by denial) is essential, given their heightened perception of threat from Russia. Southern states like Italy and Spain, which have traditionally focused either on their own periphery or the EU, have not increased their commitment to NATO’s defense planning and the protection of its eastern flank. As a result, European strategic autonomy is losing momentum and importance. Even France, a traditional supporter of EU defense efforts, is now paying more attention to NATO as the backbone of its security.

8 – In a parallel development, some governments have stressed that Europe needs to take more responsibility for its own security and especially for the security of its eastern member states. However, this would require a more coherent EU defense concept. At the same time, EU governments and Institutions see compatibility with NATO as crucial. Other countries, such as Finland, argue for a stronger EU role in security beyond classical defense. Greece also emphasizes the role of the EU, but mainly because Turkey is also a NATO member, which precludes NATO intervention in the event of an armed conflict.

9 –Countries that are currently not covered by security institutions find themselves neglected. Several European countries which are at risk of becoming a target or a lever for Russian non-military aggression and destabilization, like Moldova, are neither part of the EU nor of NATO. France has recently proposed setting up a new body, the European Political Community (EPC), to bring them closer to the EU. However, neither the EPC nor the countries associated with it currently play a role in the reflection about future politico-military missions and the role of the EPC in European defense.

NATO’s Transformation Agenda

10 – The change in geostrategic conditions goes beyond the Russian war. The most important example is the imminent accession of Sweden and Finland to NATO which will give NATO greater strategic depth in the North and regionally based capabilities.

11 – The second major factor, which serves both as a trigger and yardstick for a successful transformation of NATO, is the belief shared by European NATO members, Ukraine, and even Russia (although with a different connotation) that the United States’ role in European defense will change. Even assuming that a possible future Republican president will be less dour than Donald Trump, the midterm vector of US defense priorities is clear to all and pointing away from Europe.

12 – NATO will also face a new deterrence debate, including on the role and distribution of nuclear capabilities. The understanding of what constitutes a relevant commitment will inevitably change. This will have an impact on inputs, meaning defense spending. Here, an increase of the commitment to spending more than two percent of GDP is already under discussion. In terms of outputs, meaning capabilities, it will no longer be sufficient to offer a token or minimal contribution from a largely outdated and underequipped national force pool. The new focus on territorial defense has to be backed by NATO’s force structure – which means higher number of troops are necessary.

13 – The other debates in NATO, which primarily focus on the conventional side, will be about procurement priorities and land-based versus multi-domain operations (MDO). This could be a false dichotomy: The war in Ukraine has all the criteria of MDO instead of being primarily fought by land armies. But where some may have thought of MDO as a bloodless clash in the cyber domain or between unmanned systems, the war in Ukraine has surely destroyed such illusions. In NATO, MDO is undoubtedly seen as a warfighting concept that involves death and destruction.

14 – The gap between the usefulness of armed forces and the purpose of defense capabilities could widen. In any case, new tensions will spring up between national defense agendas, given their own competing priorities, and collective priorities and actions. In which areas will Europeans decide to continue together?

Defense Spending and Burden Sharing

15 – Many European governments have come to the conclusion that this new age of defense requires them to increase their efforts to modernize and strengthen their military capabilities. Increased defense spending is the result. Some countries have adjusted their budgets significantly, in particular Poland, Norway, Lithuania, and Estonia. The outlier is Poland, which in 2022 decided on a rapid rise in defense expenditure to around four percent of GDP. The country’s baseline budget will reach three percent of GDP, to be augmented by a special fund for technical modernization. Italy and Spain have renewed their commitment to NATO’s two percent target. However, their additional funding remains moderate. One reason certainly is that it takes time to implement change. Another reason may be uncertainty over the shape of the security threat emanating from Russia once some kind of settlement in Ukraine has been reached.

16 – Here, too, two extremes can be found, with Germany on one and France and the UK on the other side: In the Zeitenwende speech, the German government pledged to rebuild Germany’s deteriorating armed forces. To achieve this, the government committed itself to increasing the defense budget to two percent of GDP and set up a special fund of EUR 100 billion, which will count toward the expenditure goal. The UK did not announce any major budget increase in response to the Russian invasion for Ukraine. However, it had already established an extra budget to support Ukraine in response to the changed geopolitical situation after the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. France entered a commitment to regularly increase its budget in 2017; the latest announcements in January 2023 confirm this trend with an expected doubling of the defense budget between 2017 and 2030.

17 – Looking ahead, the budget discussion will be shaped by several aspects: First, there are concerns that European states may find it difficult to maintain current increases in defense spending due to economic problems or dwindling domestic support. Second, while there certainly is more money available for defense, spending needs may be growing even more quickly. As a result, the defense investment gap could become even larger than before. Finally, there is the challenge of spending the money wisely, which suggests that the efficiency of the defense bureaucracies also needs to be increased.

18 – One point stands out, both for the upcoming discussion about NATO spending levels and the taxonomy of defense expenditure: So far, non-military efforts to improve resilience, such as the protection of critical civilian infrastructure, have not played any role in the spending debate. However, given their importance for military operations, many countries have identified a need to improve civilian readiness and the protection of critical infrastructures. Hence, defense planning needs to be even more attentive to the resilience of critical civilian infrastructures.

19 – The current impetus to upgrade defense capabilities has originated mostly at the national level. As a result, there will be a nationally diversified demand for capabilities which will challenge NATO’s coordinating capabilities. In the past, having less money available did not lead to closer cooperation. It would be shortsighted to assume that more money would automatically mean more cooperation.

20 – European nations may soon reach a critical juncture: Either they are able to define a wide spectrum of missions to be conducted collectively, or, if their national priorities prove too divergent, they will be forced into a new dimension of division of labor. The ensuing discussion about specialization and reliance on allies could lead to a strategic decision that would allow the European capability pool to be shaped (intentionally). Alternatively, it could happen from the bottom up, which would force European nations to make a series of short-term adjustments (accidentally). The latter option becomes far more likely if threat perceptions, and thus the availability of resources, decline unevenly across Europe.

Level of Ambition

21 – The need to change the current Levels of Ambition (LoAs) or, more fundamentally, the approach to defining what is needed, arises from various directions. The mix of tasks demanded of the armed forces, stretching from crisis management to deterrence/defense, has an impact, as does the type of deterrence approach nations wish to employ.

22 – Ukraine has taught many countries lessons about the importance of timelines and the need for a larger pool of troops. Deterrence for many countries seems to mean increasing the readiness of forces and the number of forces at high readiness. This has implications for the overall readiness, mass, and sustainability of the armed forces. The challenge goes beyond creating appropriate frontline capabilities – it points to the need for a different technological and industrial base, with more attention focused on war production capacities and the endurance of systems in war. This has numerous implications for military mobility, logistics, maintenance, and personnel. In some cases, efforts to raise the level of ambition are compromised because of a shortage of well-trained personnel or because the conscription force is insufficiently qualified. Greece and Bulgaria in particular have reported this problem.

Accepting the Need for a Higher European Level of Ambition

The governments of most of the countries covered by this survey agree that the European level of ambition needs to be raised. To accelerate the shift initiated in 2014, Europe’s armed forces need to be able to fight high-intensity, large-scale territorial conflicts against a near-peer competitor in order to effectively deter Russia. There is also a widespread understanding that the United States is pivoting toward the Indo-Pacific region, which will challenge European states to take more responsibility for their security. For now, European militaries do not seem ready to meet these challenges.

When addressing the need for a higher level of ambition, Eastern European and Baltic countries as well as the UK focus on NATO to provide additional capabilities. Southern and Western European states consider the EU and NATO to be equally important, while France and Finland see the EU as the most important forum for European defense.

Group 1: Set Higher National Levels of Ambition

Some states (Poland, Germany, Estonia, Spain, Italy, Hungary, Norway, Romania) have not only called for higher European levels of ambition but are also stepping up their national efforts. For states like Poland, Estonia, Spain, Italy, and Germany, higher readiness and a greater contribution to territorial defense are key objectives. Germany and Poland have set themselves ambitious goals. Germany wants to turn the Bundeswehr into the most capable army in Europe. Poland declared its intention to have the most capable land force in Europe.

Group 2: Stay With Current National Capabilities

Other countries (UK, France, Finland) have not made any significant announcements to change their level of ambition. They trust in the current capabilities of their militaries and had already adjusted their strategic documents before the outbreak of the Ukraine war in 2022.

Group 3: Watch From the Sidelines

A small but significant number of states (UK, Hungary, Turkey) do not actively participate in the debate on Europe’s future military order. This is true for Turkey because of its obvious skepticism toward the EU, the UK partly for the same reason and partly because of the inward-looking bias it has developed since Brexit, and for Hungary because it does not see Russia as a major military threat.

Group 4: Focus on Territorial Defense, too

Territorial defense is back. This is a clear consequence of the Russian invasion. However, this has not led to a decrease in crisis management commitments. Countries like Spain and Italy, which have focused on their peripheries, will maintain their level of commitment to crisis management while also increasing their territorial defense efforts.

Capabilities

23 – There seems to be a need for a new combination of the elements of mass, delivery time, cutting edge technology, complexity, and sustainability in war. The Russian invasion of Ukraine is accelerating reflections and discussions. At the same time, however, there is a risk of biases such as situational overestimations. New assumptions and observations are emerging while old wisdom is being challenged: High-intensity warfare may be less high-tech than previously assumed. Should the armed forces continue to concentrate on multi-domain operations based on a greater technological edge, information superiority, and agility? Large-scale, long-lasting wars have been underrepresented or even ignored in planning. Now, equipment fragmentation has evolved from a theoretical problem to an eminently practical issue that presents challenges for logistics and maintenance, repair, and overhaul (MRO). In the short term, land and air forces may be receiving more attention. But nations with the experience of classic naval missions will hold on to those capabilities. The challenge presented by scarce resources will accelerate the division of labor. Decisions on technological pathways, for example the use of unmanned systems, will be taken more quickly. The same is true for dealing with gaps and legacy systems.

24 – Several contributions highlight the need to strike a new balance between acquiring complex, state-of-the-art capabilities (which can only be produced in small quantities) and making less complex weapon systems available on a large scale. This choice will have significant implications for procurement and industry. Obtaining mass-produced goods in sufficient quantities is both difficult and important; therefore, the ability to fight a long war needs to be supported by industry. The more supportive industry can be, the more the equation between innovation and production will shift in favor of manufacturing.

25 – Fragmentation has been identified as one of the main challenges to raising the European level of ambition. European defense efforts remain incoherent, in particular with regard to procurement. Defense industrial cooperation between European countries is not yet delivering the benefits in terms of cost savings and interoperability that it should. Governments have been purchasing off-the-shelf products because of their need to rapidly upgrade capabilities. However, this has led to a loss of momentum in joint European procurement and development.

Group 1: Modernization and Speeding Up Procurement

Several countries (Poland, Lithuania, Estonia, Germany, Bulgaria, Finland) have announced changes to the personnel structure of their armed forces. Hungary and Estonia will increase the number of troops significantly, too.

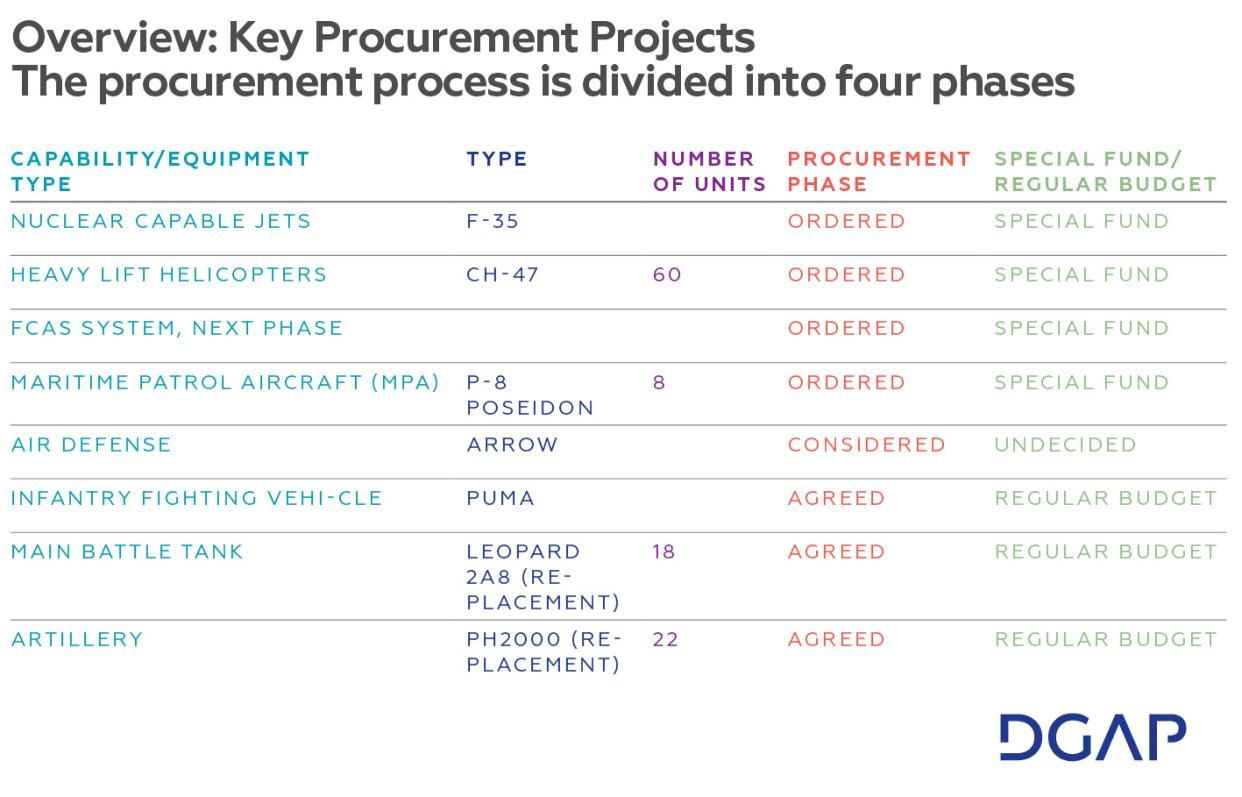

Most other countries focus on procurement. In the case of Germany, Italy, and Estonia, they are procuring a range of new capabilities, including sixth-generation fighter aircraft. Others, as for instance Finland, are accelerating existing procurement programs. The common focal points of all the programs are air defense systems, modern combat aircraft, and long-range artillery systems (especially in the Baltics). Poland is a prime case of heavy investment directed toward developing its land forces branch.

Group 2: No Major Adjustments

Some states – UK, Norway, France, and Spain – have not yet translated higher European levels of ambition into concrete adjustments to their national defense structure or equipment procurement. These are the same states that have not adjusted their national level of ambition.

Overall Tendency: Focus on the Land Domain

Although the picture is not entirely clear, there seems to be a tendency for the land domain to receive more attention in the allocation of new funds. This makes sense, as territorial defense depends on credible land forces. However, such a shift in investment may put a question mark behind multi-domain operations and concepts.

Defense Technological and Industrial Base

26 – Europe’s difficulties in supplying Ukraine with the necessary equipment and munitions to defend against Russia show that that the European defense industry is ill-prepared to support a large-scale war in terms of both arms and ammunition production. Production capacities were significantly reduced over the last decades as a result of the financial crisis and threat assessments that focused on crisis management rather than territorial defense. Many defense companies shifted production to high-value, complex weapon systems manufactured in small numbers. However, large-scale war requires more mass, which the EDTIB is currently unable to deliver.

27 – Reduced funding means that even in larger industries like Germany’s, some production capacity has been lost. Also, many industries are hampered by personnel shortage and slow procurement processes. Only the UK and France were able to maintain almost the full range of capabilities due to their relatively high level of funding in the past.

28 – The Russian war has not led to major adjustments at the DTIB level due to additional or modified procurements, nor have there been other reasons for scaling up activities. Countries with large industries like the UK have not increased their defense budgets, while countries with smaller NTIBs like the Baltic States do not have the technological edge or production capacity to benefit from increased national funding. However, some industries are experiencing a moment of revival.

29 – The case of France remains somewhat ambiv- alent. On the one hand, the French President Emmanuel Macron announced the need for a „war economy,” on the other hand, French industry remained reluctant to increase production capacities, as no new procurement programs were announced that would have made industry confident that higher production capacity would pay off. However, of all the countries in the survey, France was the only one to announce a reform of procurement procedures.

30 – Turkish and Hungarian industries have been growing for a few years due to increased defense spending and modernization programs. However, these efforts were not a consequence of the war in Ukraine but were initiated before.

Group 1: US-Dependency in Central and Eastern Europe

Most states in Central and Easter Europe are heavily dependent on the United States for their defense equipment. This makes them less open to intra-European defense cooperation. Another factor is the relatively small size of their NDTIB, which makes off-the-shelf purchases and offsets more attractive. Also, the additional bureaucracy required to set up European programs often outweighs the potential gains of economies of scale. Delays, typical for multinational programs, are also seen as a handicap which weighs all the more heavily given the acute character of some capability gaps. There are exceptions to this tendency, for instance Romania, which participates in several PESCO and EDF initiatives.

Group 2: No Clear Picture of Cooperation Potential

Although Western European states are more engaged in European defense cooperation and strongly support the further development of PESCO and EDF projects, no clear areas of potential cooperation could be identified from this survey. On the contrary, the Russian invasion has led some key stakeholders in EU cooperation to rely more heavily on off-the-shelf systems mainly from the United States. The German decision to buy F-35 aircraft is a case in point. The French government in particular is disappointed by such tendencies. It does not look as if the war in Ukraine would be giving a new impetus to European cooperation.

31 – Industrial policy with a focus on national DTIBS could further divide Europeans in terms of defense production, procurement, and operations. For the time being, there is no significant push for European DTIBs. While Europe hosts some multinational defense companies like Airbus, MBDA, Thales, or Leonardo, these are driven by national procurements rather than European ones. The current call for filling gaps and increasing stocks in the context of the war in Ukraine does not provide sufficient political direction and scale to keep the European DTIBs alive.

32 – The future of European DTIBs will be driven by the Western European states with large industries and countries that can invest significantly in future defense procurement and innovation. Off-the-shelf national procurements and acquisitions from extra-EU partners weaken European projects and EU institutional pillars for a more unified European DTIB. Yet in the context of the Russian war, there are many cases in which only non-EU partners can provide the capabilities quickly enough.

The Future

33 – European defense is an open system with highly interdependent core issues. Debates and decisions on one element can have unintended consequences for many other elements of the system. The future of Ukraine, Russia, and the United States’ engagement in Europe are interacting variables that define the system just as much as the future defense path of more than 40 European nations. A more Europeanized defense requires a new consensus on the strategic outlook, the level of ambition, but also on the purpose and role of the military and corresponding capabilities.

34 – The Russian war against Ukraine has created the need, but also the opportunity, to generate a new consensus in the overlapping circles of NATO and the EU. European countries that do not yet belong to these institutions should be included in the process. The proposed European Political Community could offer a political opportunity for making a new start toward European security.

35 – Europe may be more divided than expected in its response to the future of collective action. What are now differences in nuances could turn into deeper rifts once the war is over or difficult compromises have to be made. Looking back to the state of relations after the fiscal crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic could be instructive for anticipating what European governance will be like after the end of the Russian war.

36 – Discussing end-of-war scenarios and their implications for European defense, while necessary, may have collateral effects and put governments into paradoxical situations. Moreover, allocating more resources is so urgent that it is imperative to preserve the unity of Europe. Holding a potentially divisive discussion over possibly hard-to-align objectives could make it difficult to agree and achieve collective action.

37 – However, Europe will also have to address other threats than Russia. A diversification of the risk and threat landscape should be expected and accepted as part of the reality and complexity of European security. The problem of collective action and individual actors trying to pursue objectives on the margins is by no means a new phenomenon. On the contrary, it is constant factor in collective politics.

38 – Future deterrence will need to incorporate several aspects: At the strategic level, the challenge will be how to deal with strategic surprise and nuclear blackmail (in the German case, Russian propaganda threatening with nuclear escalation influenced the public debate). But questions of capabilities and capacities will also have to be reassessed. The ability to fight a long war not only has implications for the DTIBs that sustain such a war, but reserves and readiness also play a role in this complex equation. The ability to fight a long war could all by itself become a deterrent: An aggressor should not believe in being able to obtain a quick victory.

39 – Alliances and partners: Smaller countries like Estonia and Latvia are particularly vulnerable to the policy choices of their partners. Frictions can arise when partners do not share their approaches, for instance on the need to shift toward a posture of deterrence by denial. Nonetheless, interoperability is of great benefit here, too.

40 – Dealing with Russia: All experts who contributed to this survey agreed that even after the war in Ukraine has ended, Russia will continue to pose a serious threat for Western allies. Russia’s great power ambitions will remain a serious challenge to the territorial integrity of its neighbors and the European security architecture. Therefore, the future of the Russian threat to European security depends on three variables:

The immediate outcome of the war in terms of the Russian posture: Even after the war, Russia will have a fearsome military. While the army will be severely depleted and the air force weakened to some extent, the naval and strategic forces will be intact.

Moreover, what lessons the Russian leadership will draw from the conflict at the political, strategic, and military levels and how it organizes that learning process will be critical.

The political and military priorities of the United States and its commitment to NATO will also heavily influence the level of threat that Russia poses for Europe.

41 – How to deter Russia may become more and more of a guessing game in the near future, as Russian perceptions of security and threats will become less and less comprehensible. Europe’s immediate task is to rebuild its knowledge of Russia and the post-Soviet space as a political and social sphere. In part, Europe has seriously misunderstood Russian intentions and ambitions, resulting in a naive attitude toward the current Russian leadership. There is an urgent need to rebuild expertise on Russian society and politics. Only then will it be possible to identify effective approaches to tackling the root causes of the war. In the meantime, a fundamental objective should be to deny Russia quick victories with which to bargain. As a short-term strategy, it is crucial to reduce Russia’s leverage in international negotiations. What has also not been exploited are the pressure points offered by the Russian international presence and its weakening through war.

Ukraine: Lessons Learned and Future Support

42 – The question of Ukraine’s future – short-term and long-term – in the European strategic landscape is by far the most important issue. It affects not only Ukraine’s immediate need for support but also has an impact on the course of the war and on how and when it will end. It will therefore also shape the state of Russia’s posture and strategic options at that time. However, the state of affairs right after the end of the war will not define the character of Ukrainian and Russian attitudes in the more distant futures, i.e., the 2030s. Both sides will continue to aim for outstanding military capabilities. This will take place in reference to the respective other side and will be supported by partners. Ukraine is likely to receive high quality capabilities from the West for a long time even after the “hot war” is over to ensure minimum deterrence vis-à-vis Russia. Thus, Ukraine and Western Russia may remain a focal point of geostrategic conflict in Europe, with their border serving as a demarcation line between two political spheres.

43 – From this point of view, the question of the quality of military assistance to Ukraine gains in strategic relevance as well as urgency. Whether Ukraine wins the war or not will make a difference for the next chapter of the confrontation. It will also set the parameters for Western relations with Ukraine. The country will be an important deterrent for Russia which will shift some of the burden away from others European nations.

44 – So far, NATO allies cannot agree on how far they are willing to go, and which sacrifices they are willing to make, to help Ukraine win the war. Part of the problem may be that they are either not yet clear about the long-term strategic importance of a Ukrainian victory, or they have concluded that Ukraine is not essential or as important to their security as other issues.

With Russia’s full-scale attack on Ukraine in February 2022, European defense has entered a new era. This is currently characterized by a new unity of Western allies, an increased focus on NATO as the main provider of European security, and a heightened sense of the importance of territorial defense. However, Europe is more divided than it seems. The country reports show that there are diverging underlying trends regarding defense spending, threat perception, and capability outlook. The same is true for European countries’ support to Ukraine. The NATO summit 2023 in Vilnius can help and shape these developments. But political statements will need to be backed up by an increased effort for cooperation especially among the Europeans. Taking more responsibility for European defense is a conditio sine qua non for the European nations, no matter which role the United States will play in and for Europe in the future.

Europeans cannot just focus on the European theatre and defense; they must adjust to a more complex geopolitical equation. The most important example is the potential for a conflict between the United States and China, which would affect much more than just the military domain. Any such conflict would have implications for Europe’s solidarity with the United States as well as for the military capability gaps that a rapidly increasing US engagement in Asia would mean for the European theatre. European states will therefore have to solve a difficult equation when it comes to defining their future defense ecosystem, taking into account their security and defense policies, capability profiles, and the required technological-industrial base, as well as what they need to do collectively, be it within NATO, the EU, or in multinational coalitions.

Introduction

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 set off a dramatic shift in the European security landscape – European defense is entering a new era. However, the changes are far from uniform across the continent.

This publication analyzes the consequences of the Russian invasion for the European defense ecosystem. It examines how the war has changed perceptions of the European security landscape and what impact it is having on the continent’s future military order, the European Defense Technological and Industrial Base (EDTIB), and on defense cooperation both in a broader sense and in terms of defense-industrial cooperation. This publication is part of a long-term project on European Defense In a New Age (EDINA), partly carried out in cooperation with the Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom (FNF).

In January 2023, DGAP and FNF brought together defense experts from European NATO members (Germany, France, United Kingdom, Spain, Italy, Norway, Finland, Greece, Turkey, Poland, Hungary, Romania, Lithuania, Estonia, Bulgaria) for a workshop on the changes underway in the European defense ecosystem. Their collective findings formed the basis of a paper published by the FNF at the Munich Security Conference 2023. This summary is an adapted version of that publication.

In preparation for the workshop, experts were asked to prepare country reports as input for the workshop and a starting point for discussion. The reports were based on a questionnaire based on the four categories mentioned above:

The Geostrategic Landscape: New Realities

- How does your country’s government assess the new geostrategic environment (Russia and beyond)? (Changes/Continuities)

- Which (changing) priorities result from that regarding security and defense policies?

Europe’s Future Military Order

- What are the implications for the military’s level of ambition and tasks?

- What are the main challenges to achieving those ambitions and tasks, and what are the proposed solutions?

- What are the key developments regarding force structure/personnel and procurement/equipment?

The Future European DTIB (Defense Technological and Industrial Base)

- How has the DTIB responded to the changed circumstances (companies, government)?

- Are there any concrete plans/announcements that impact industrial capacities or technology development?

Cooperation

- From your country’s perspective: What are the most important cooperation formats/projects?

- Are there potential areas discussed for cooperation among governments/armed forces or on the industrial level?

After the workshop, the authors had the opportunity to adapt their reports in the light of the discussions. The reports informed both the workshop and the FNF publication. They provide a unique insight into the process of change affecting the European defense ecosystem.

The key findings are followed by the country reports. They have been slightly edited to meet grammatical and spelling standards. Any opinions expressed in the reports are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the German Council on Foreign Relations (DGAP).

Country Reports

-

Bulgaria

-

by Jordan Bojilov, Director, Sofia Security Forum

Summary

Bulgaria supports the development of European defense and participates in all common initiatives, although it has no separate strategy for participation in them. Efforts to build European defense should not duplicate NATO, which remains the backbone of common defense, especially territorial defense. Bulgaria sees the development of the European capabilities as a tool to cope with numerous challenges. The country‘s participation in European defense projects is an opportunity to increase the capabilities of the armed forces and to modernize the technological and production base.

Bulgaria is developing enhanced defense cooperation with neighboring countries, in particular Romania and Greece, in areas such as air defense, joint training, and others. This cooperation could be extended to the joint acquisition and sharing of armaments and equipment or the creation of joint capabilities, but no such project has been implemented so far.

Bulgaria supports multinational projects within the EU and NATO that would lead to the development of key capabilities while optimizing the acquisition and maintenance costs of participating countries. Bulgaria participates in several projects such as the Strategic Airlift Capability, AGS, a European missile defense project, and others. It is believed that participation in such projects also leads to better interaction between allies.

Another key issue for the country is support for investment in defense companies to produce weapons and equipment to NATO and EU standards. For this reason, the Bulgarian ministry of defense equires foreign companies participating in modernization projects to invest in the Bulgarian defense industry. This is seen as an opportunity not only to acquire technology but also to provide much-needed investment funds.

The Geostrategic Landscape: New Realities

Russia‘s aggression against Ukraine is undoubtedly the most serious challenge to peace and security in Europe and the world. It was a wake-up call for many politicians in the country that security and defense need to be taken more seriously. The question of the role of NATO and the EU in the defense of Europe, and of Bulgaria in particular, became a central issue in public debates, including on Bulgaria‘s role and participation in the common defense.

It should be noted that despite the prevailing assessment that the war in Ukraine is the most serious challenge to European peace and security, the attitude of politicians and Bulgarian society toward the war as such and toward Russia remains ambiguous. After the outbreak of hostilities, approval of Russian President Vladimir Putin among Bulgarians fell dramatically, but the majority of Bulgarian society still has a positive attitude toward Russia. This can be explained, among other things, by the long-standing historical, cultural, and other ties between the two countries. At the same time, the vast majority of Bulgarians remain committed Europeans and Euro-Atlanticists.

On November 3, 2022, the newly elected Parliament by a large majority condemned the aggression of the Russian Federation against Ukraine as „the most significant threat to peace and security in Europe.” With the same decision, it voted to provide direct military aid to Ukraine, but some of the parties – Socialists and Nationalists – categorically opposed the donation of arms to Ukraine. Some political parties and many Bulgarian citizens still see the war in Ukraine as a bilateral conflict between Russia and Ukraine and not as a major geostrategic rift and a crisis of the international security architecture.

At the same time, it is hard to define the position of the Bulgarian government regarding the war or military assistance to Ukraine. There are rather diverse positions of different governments depending on the political parties participating in the coalitions. Since 2021, Bulgaria has been in a constant political crisis with frequent changes of government. For example, the previous regular government in June 2022 assessed the Russian military aggression in Ukraine in a categorical manner „as a threat to peace and security in Europe and a direct challenge to NATO and the EU.” The current caretaker government has a different assessment. This was most clearly expressed by the defense minister on December 13, 2022, when he stated in the Parliament that „because of the war in Ukraine there are risks for national security because of the proximity of the conflict, but there is no real threat to the country’s security at the moment.” These risks are seen as a secondary consequence of the war, such as refugees, floating mines in the Black Sea, problems with energy sources, inflation, etc. The war is not perceived as having a direct impact on the country.

As mentioned above, the population remains divided in its assessment of the war for many reasons, to mention only the general positive attitude toward Russia as the liberator from the Ottoman Empire, cultural ties, widespread pro-Russian propaganda, divergent messages from different political parties, lack of common strategic communication, and many other factors.

The fact that the war is being fought just a few hundred kilometers from the country‘s borders heightens the sense of risk and pushes politicians to look for ways to mitigate it. Despite the different assessments of the war, the vast majority of political parties agree that the defense capabilities of the Bulgarian army need to be further developed. Undoubtedly, NATO and the EU are seen as the most important factors in protecting the country‘s security. Bulgaria strongly supports all NATO and EU measures aimed at strengthening the eastern flank, providing Ukraine with assistance, including military, and putting pressure on Russia to stop its aggression and withdraw its troops from Ukrainian territory. As part of these measures, a multinational battalion combat group led by Italy has been deployed on Bulgarian territory.

Europe’s Future Military Order

Bulgaria supports the development of the Common Security and Defence Policy and the strengthening of European defense capabilities. Located on the eastern border of both the EU and NATO, it considers itself particularly vulnerable to external risks and threats. There is an understanding that Europe should develop mechanisms to realize its priorities. In this context, Bulgaria participates, for example, in PESCO projects. At the same time, it can be said that the country participates in the construction of European defense with moderate enthusiasm. The main principle followed by Bulgarian governments is that NATO is the core of the collective defense of the whole Euro-Atlantic area. National documents state that „NATO and the EU should work together, complement each other, and do everything possible to strengthen both organizations. NATO remains the main guarantor of security and the achievement of the EU’s strategic autonomy is possible only on the basis of the transatlantic bond.“

There is a generally accepted position among politicians that Bulgaria‘s commitments and cooperation within the CSDP will be compatible with commitments to NATO. A guiding principle is that efforts to build European defense should not duplicate efforts within NATO. This is mainly motivated by financial and economic considerations, as the country cannot afford to allocate more resources to defense and create capabilities for the EU separate from those for NATO. Most political parties accept that NATO is the core for collective defense, including the defense of the European continent. European defense is seen as a European pillar of NATO.

The war in Ukraine has put on the political agenda the need for decisive modernization of the Bulgarian armed forces. However, there has been no decision to seriously increase the defense budget, which is expected to reach two percent of GDP by 2024.

There is no doubt that the Bulgarian armed forces are in need of decisive modernization. The main challenge is that the main combat systems get produced according to the standards of the former Warsaw Pact, some of them were produced in the former USSR and are morally and physically obsolete and incompatible with NATO and EU standards. The main objective of the modernization is to acquire new, modern platforms that meet NATO/EU standards. The Bulgarian MOD has developed an ambitious modernization program, but due to a lack of financial resources, its implementation cannot be ensured in the short or even medium term. For the development of key capabilities, the Bulgarian Armed Forces will rely on the defense budget, but also on assistance from allies. In this regard, participation in multinational EU and NATO projects is an opportunity to acquire new capabilities and to bring the country to a new technological level. The latter is crucial, as the Bulgarian defense industry is currently virtually excluded from the modernization of the army.

In recent years, Bulgaria has acquired various NATO-standard platforms, including 16 new F-16 Block 70 fighter jets from the United States, transport aircraft, helicopters, and vehicles. A project to build two battleships for the navy is underway. There are several other priority projects, including the purchase of new infantry fighting vehicles, radars, drones, etc.

Key to the modernization of the armed forces is a high level of integration with NATO and the EU. This includes more training and exercises with allies, participation of Bulgarian soldiers in joint operations and activities, etc. The chronic shortage of personnel remains a serious challenge. Almost 20 percent of posts are vacant, and the situation is not improving. There are not enough applicants to serve in the armed forces, as service in the armed forces remains unattractive due to low salaries. At the same time, more than 70 percent of the military budget is spent on personnel, reducing the amount available for the acquisition of new systems and weapons. It is a challenge to find a balance so that more money is spent on personnel, new equipment, and training.

National Defense Technological and Industrial Base (NDTIB)

In recent years, the Bulgarian defense industry has exported production worth about EUR 1 billion annually, mainly to countries in Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. In 2021, exports increased many times over due to the war in Ukraine. Large quantities of arms and equipment were exported from Bulgaria to Ukraine through private companies.

Most of the companies in the Bulgarian military production complex were built during the Cold War to produce and maintain weapons and equipment to the standards of the former Warsaw Pact. Since Bulgarian companies have enough orders for weapons and ammunition to Warsaw Pact standards, they have no interest in switching to NATO standards.

At present, with a few exceptions, all companies are privately owned, which deprives the state of the possibility of influencing production and providing resources. The state has distanced itself from research and development (R&D). Human resources in research are in constant decline due to low salaries, better opportunities in other industries, or better offers from the defense sectors of other countries.

Since companies do not produce military equipment, weapons, and ammunition to NATO/EU standards, the Bulgarian defense industry is in practice excluded from participation in the modernization of the armed forces and cannot take part in multinational EU or NATO projects.

For its modernization plans, Bulgaria has to buy new systems from its allies without being able to engage its own military-industrial complex, which is seen as a serious problem. A key issue is the division of countries from different parts of Europe into 'producers' and 'buyers'. This issue needs to be addressed at the EU level in order to ensure the geographical balance of the common European defense market.

It is worth noting that there is interest on the part of Western companies to invest in local production, but the investments are made subject to the receipt of orders for military equipment. An alternative for the participation of Bulgarian companies in multinational projects is the involvement of high-tech, innovative companies developing new technologies or intellectual products. The country is currently debating how the state can support such companies.

Cooperation

Apart from its participation in several PESCO projects, Bulgaria has not established deeper cooperation in European defense projects.

For Bulgaria’s defense, the strategic partnership with the United States is key. An agreement on defense cooperation was signed with the United States in 2006, allowing for the joint use of facilities and the stationing of a certain number of US troops on Bulgarian territory. Such strategic cooperation has not been implemented with any other NATO and/or EU member state. Currently, a multinational NATO battlegroup led by Italy is deployed on Bulgarian territory as part of efforts to strengthen the eastern flank. This is seen as an opportunity to develop deeper bilateral relations between Bulgaria and Italy.

-

Estonia

-

Tony Lawrence, Head of Defence Policy Strategy Programme, International Centre for Defence and Security, ICDS

The Geostrategic Landscape

Since the restoration of its independence, Estonia’s foreign policy, security, and defense discourse has been dominated by consideration of the threat posed by Russia, often going against the grain of attitudes and policies prevalent in other Western states.[69] Nevertheless, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 was a shock. Its brutality and scale—the land captured by Russia in northern Ukraine alone in a matter of days in its failed attempt to take Kyiv amounts to around 60 percent of Estonia’s territory—and its stark rejection of European norms and values vividly confirmed for Estonia the utter incompatibility of Russian and western conceptions of security for small states.[70]

The invasion was also seen as a vindication of Estonia’s perceptions of and policies toward Russia and an implicit condemnation of those western states that had allowed themselves to be misled about Russia’s nature. While Estonia has taken substantial additional steps to build up its own defense during 2022, a key foreign policy aim has thus been to persuade other European states of the need to (finally) take the Russian threat seriously and take similar actions. The country has also been at the forefront of those urging tougher sanctions on Russia, in particular in the energy sector.

The European security environment is seen to have changed radically. Of course, the outcome of the war cannot be known, but because of Russia‘s unrepentant behavior and its continued aspirations to restore its great power status, Estonia expects Russia to find itself excluded from any future European security arrangements. Estonians have been quick to condemn suggestions from Western partners that Europe can return to business as usual with Russia, that future security arrangements must take into account Russia‘s special interests, or that Ukraine must make concessions in the service of peace. On the contrary, Estonia‘s immediate foreign policy priorities are that Russia be comprehensively defeated, that it be held accountable for its crimes of aggression and the physical damage it has caused, and that Ukraine‘s territorial integrity be restored. These conditions are seen as essential for sustainable security: Lesser outcomes would simply not deter Russia from future aggression.

Throughout the war, the government has insisted that there is no direct military threat to Estonia. However, while Russia‘s conventional forces have been weakened by Ukraine, it remains a credible nuclear power and will rebuild its military. Meanwhile, it retains the ability to attack Western states in the grey zone. The war has thus given Estonia, and Europe more broadly, a short period in which to prepare for a future Cold War-like situation.

In such circumstances, military power will become increasingly important. Diplomacy and dialogue with Russia have failed, at least without the backing of military power, and Europe must now take action to reverse decades of military decline (while continuing to provide maximum military support to Ukraine). Capability gaps must be filled and sufficient stocks built up for a prolonged conflict. Meanwhile, the precarious situation calls for continued U.S. engagement in European security, including military engagement. NATO will therefore remain an indispensable institution. The EU, meanwhile, has found a strong role for itself in supporting Ukraine in the war and should build on this to complement NATO, leaving behind the more controversial (hard security and defense) aspects of strategic autonomy. Both organizations need to recognize that grey and buffer zones are sources of instability and that vulnerable states on Europe‘s periphery need to be brought into Western security structures.

While Estonia‘s security considerations are for now overwhelmingly focused on Russia, there is also a recognition that European states must not make the same mistakes in becoming dependent on China.

Future Military Order

Estonia has contributed steadily and at a reasonably high level to international operations since the 1990s – most recently, following its involuntary withdrawal from Operation Barkhane in mid-2022, it has announced its intention to send a company to participate in the US-led Operation Inherent Resolve in Iraq this year – but this has never been a driver of force development. The core task of Estonia’s armed forces has always been to provide territorial defense, both independently and with allies. Russia has been regarded as the only potential threat to peace and security in the region, and defense efforts have been aimed at building armed forces of sufficient size and capacity to deter, and if necessary, defend against Russia. The focus has been on the training and equipping of reserve-based land forces.

The main challenge is one of resources. Estonia‘s defense forces are well funded according to NATO guidelines, but the country and its economy are small, certainly compared to Russia, which has built up large and seemingly capable forces in its Western Military District. To fill the gap, Estonia, along with other allies on its northeastern flank, has sought to engage the rest of the alliance in Baltic security. The most visible successes of these efforts have been Baltic Air Policing and the enhanced Forward Presence.

Russia‘s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has not altered this approach in principle, but it has increased the sense of urgency and led Estonia to call for a substantial change in the means of implementation. Estonia (along with Latvia and Lithuania) has essentially rejected NATO‘s post-2014 deterrence posture, in which the enhanced Forward Presence would act as a tripwire in the event of an armed attack, triggering large-scale allied reinforcement and territorial restoration operations. The three countries have argued that Russia‘s brutality in its war in Ukraine has shown that it simply cannot be allowed to set foot on allied territory – Baltic territory should not be restored by NATO but defended from the outset. In the run-up to and at NATO‘s Madrid Summit, they advocated a shift from deterrence by punishment to deterrence by denial (often referred to as ‚forward defense‘), which would require more and different military capabilities and higher-level command structures in the Baltic region.

For their part, the three states increased spending and began to invest in new capabilities. Through two decisions in early 2022, the first even before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Estonia allocated more than €800 million of additional funding for both military and non-military defense in 2022-5. Defense spending in 2022 is now estimated to be 2.34 percent of GDP (EUR 771 million). The government plans to spend 2.85 percent of GDP (EUR 1.098 billion) in 2023 and 3.26 percent of GDP (EUR 1.317 billion) in 2024.[71] Estonia‘s political parties, which are currently positioning themselves for the March 2023 parliamentary elections, all call for defense spending to be at least 3 percent of GDP in the coming years.[72]

Much of the increased funding will be used to build readiness, including substantial sums to procure ammunition to build wartime stocks. Estonia’s territorial defense units will be doubled in size to 20,000, largely by assigning reservists (former conscripts) who had no dedicated wartime role to new reserve structures. The government has established a ‘divisional structure’ under the framework of NATO, which will see the defense forces establish a division headquarters to which the Estonian 1st and 2nd Brigades and several support units, and an allied (mostly UK) brigade will be assigned. A new garrison and training area will also be established in southern Estonia to meet the needs of the enlarged wartime structure—36,000 personnel—and to accommodate a brigade-sized allied contingent.

The additional funding will also allow some big-ticket investments to be brought forward. The procurement process for two medium-range, ground-based air defense batteries has begun, a EUR 200 million contract for six HIMARS multiple launch rocket systems has been signed (much of the funding is from US Foreign Military Financing), and a further twelve K9 Thunder self-propelled howitzers have been ordered from South Korea for EUR 36 million to bring the total fleet size to 36, while a joint project with Latvia, worth EUR 693 million over ten years, will allow a range of logistical and other vehicles for the defense forces and other agencies to be procured.

Cooperation

Estonia participates in five PESCO projects, two of which it coordinates (Integrated Unmanned Command System, and Medium-Size Semi-Autonomous Surface Vehicle). The country is keen to build on its high-tech (cyber) reputation and sees autonomy as one of its key strengths. Estonian companies participate in several EDIDP-funded projects (EUR 6 million in 2021).[73] With the UK, Estonia is the joint host of the European regional office of DIANA, while an Estonian official currently heads the transition team setting up DIANA.

However, most of Estonia’s defense acquisition is off-the-shelf procurement of mature technologies, where the savings possible through economies of scale may not be worth the additional investments in the bureaucracy of international cooperation. This, combined with the need for Estonia and its most likely cooperation partners to make substantial additions to their defense budgets in a short period of time, means that opportunities for acquisition cooperation are rather limited. However, in addition to their recently announced joint procurement of logistics vehicles, Estonia and Latvia have signed a Memorandum of Understanding to jointly procure ground-based medium-range air defense systems through the Estonian Defence Investment Centre.

The opportunities for cooperation in operational matters are somewhat more extensive. Estonia’s key partner here is the UK, which is the framework nation for the enhanced Forward Presence Battlegroup in Estonia, entailing regular and extensive cooperation. The UK will also assist Estonia in developing its new divisional structure, to which UK forces will be assigned in times of crisis. Another important development has been the discussions with Finland concerning cooperation in coastal missile defense – Estonia has recently acquired Blue Spear anti-ship missiles from Israel.

The United States also remains a key partner. Estonia would not wish to see opportunities for defense cooperation with or procurement from the United States excluded by the development of protectionist European policies. The HIMARS procurement is an important development in this regard, as is the recent return of a rotating US infantry company (the US rotational presence in Estonia was halted shortly after the deployment of the enhanced Forward Presence).

-

Finland

-

Charly Salonius-Pasternak, Leading Researcher, Finnish Institute of International Affairs (FIIA)

The Geostrategic Landscape: New Realities

By applying to join NATO in 2022, the Finnish security policy leadership (key government ministers and the president) has sought to further strengthen the network of international security cooperation that has been built up over the past three decades; hence the argument that Finnish NATO membership is only the latest step in a broadly consistent foreign policy path. However, the pursuit of NATO membership reflects a new assessment of how to deal with a changing security environment in Europe within a broader global geostrategic framework; hence the argument that Finnish security policy has changed dramatically in 2022.

Overall, the evolving recognition that the security environment was changing can be seen in post-2014 government security reports, but a geostrategic ‘great power competition’ -framing only emerged in the 2020 report. Despite this, for a number of reasons, only Russia’s expanded attack against Ukraine in February 2022 resulted in a broad political and societal recognition that the security environment had changed so dramatically that Finland needed to make dramatic changes to its security policy – seeking NATO membership.

For Finland, this change did not mean a shift away from the core instinct to seek improvements in human rights, support for international institutions, and the desire to address major global challenges through a multilateral approach remains. The post-2020 framework of global great power competition has led to a more geopolitical and geo-economic perspective in Finland's foreign and security policy, and NATO membership will further strengthen this framework.

At the global level, this means understanding that the European Union remains Finland's most important global security linchpin, especially in addressing climate change, technological challenges, and (geo-)economic competition. The impact of NATO membership will depend on how active NATO itself is beyond its Euro-Atlantic remit. At the regional, Euro-Atlantic (and MENA) level, Finland's NATO membership is perhaps the most consequential, as NATO becomes a key forum for Finland to discuss regional geopolitical issues and prepare for deterrence and regional defense. However, the EU will remain the more important of the two memberships in terms of overall security.

At the national level, the war in Ukraine has reinforced the belief that Finland's approach to national defense is broadly correct and that NATO membership is seen as an additional layer of deterrence (including nuclear) and, if necessary in the future, defense. It is also recognized that NATO membership will inevitably require Finland to develop and take positions on issues relevant to global security that it has not been able to address so clearly before (e.g. nuclear weapons, specific technology transfer and trade issues).

Europe’s Future Military Order

Neither the great power framework nor Russia’s expanded aggression against Ukraine has changed Finland’s fundamental understanding of, or approach to, the role of the military. This is because, unlike most European states, Finland had not changed the basic tasks of its military in the post-Cold War environment, maintaining a robust national defense capability. It is clear, however, that Russia's attack provided the domestic political support for further strengthening national defense through emergency funding to increase stocks and accelerate some ongoing procurement projects (especially for materiel that the war in Ukraine has shown to be particularly useful). The Russian attack also allowed Finnish security leaders to publicly acknowledge that a deterrence posture based solely on Finnish defensive capabilities, while robust, was not sufficient due to the fundamental asymmetry in military capabilities with Russia (in terms of volume and nuclear capabilities).

The key future military challenges are related to Finland's forthcoming NATO membership: (1) contributing to NATO's ongoing deterrence activities and integrating Finnish and NATO defense plans; and (2) the strategic cultural change from „defending alone, hopefully with others“ (the latter part especially since 2014) to being part of a „collective defense family“. Despite NATO membership, there is a clear sense among Finnish politicians and the population at large that it is always Finland and the Finns who are ultimately responsible for the defense of the country – that external assistance is complementary to the national defense capability.

Officially, Finland is reluctant to comment publicly on how it might contribute to NATO's ongoing deterrence activities, with officials stating that the focus must be on achieving membership, not on getting ahead of the game. Unofficially, Finnish and NATO officials have discussed what Finland's contributions might be, for example to the eFP units, the air policing missions (Baltic and Icelandic), and the Standing Maritime Groups (SMGs). Since Madrid, Finnish and NATO officials have exchanged more information and ideas on defense planning, but actual defense planning will have to wait. It is likely that Finland could contribute a company to the British-led eFP, with a full battalion available in Finland at short notice. Baltic air policing could also be done from Finland, but contributing to rotations (and extending the time present) in Iceland would probably be a more welcome contribution. Sending a Finnish MCM ship to the Mediterranean could be an easy way to contribute to NATO’s maritime operations.

Recent developments in force structure, personnel, and procurement are largely independent of developments in Ukraine. The most important examples are the selection of the F-35 as Finland's future fighter jet (December 2021), the ongoing project to begin construction of the Finnish Navy's new large surface combatant, the Pohjanmaa class (nee Squadron 2020), the high-altitude air defense system (downsized to two Israeli-origin systems in 2022), and the goal of increasing the cadre force by a few hundred more officers and NCOs.

Russia's attack on Ukraine has accelerated some procurement projects, such as anti-battery radars and various drone systems. In addition, most of the extra EUR 600-800 million that the government has added to the defense budget (for 2022-23) has been spent on increasing stocks of critical material (such as long-range artillery/rockets, anti-tank systems, personal protective equipment, communications, and sensors (including NVGs). Some of the money has also been spent on a sharp increase in training exercises, particularly for reservists.

The official view, supported by unofficial estimates by external analysts, is that the Finnish military has never been in better shape, with high readiness and capabilities that match the security threats well.

National Defense and Technological Industrial Base (NDTIB)

The DTIB in Finland is relatively small, with only a few small prime contractors (Patria being the most important). Discussions with industry representatives, the government, ministries and the Defense Forces revealed a lack of initial understanding of the realities of defense procurement, particularly with regard to the time and financial requirements for opening new production lines. Finland was accustomed to 'piggybacking' on other larger orders (made through NATO, EU, or bilateral cooperation) rather than being the initiator of new production lines. This reflected the bureaucratic experience and established policy of previous decades. By the end of 2022, this understanding had improved.

There are many discussions that Finland is having directly with the industry, with its current partners and future allies. The main conceptual discussions revolve around balancing immediate needs with creating a sustainable approach that does not lead to overcapacity. How to support Ukraine in 2023 is also a concern, as most industry sources indicate that production cannot be seriously ramped up until governments jointly decide to do so and finance it with at least some multi-year, longer-term contracts. In Finland, the defense establishment continues to strike a balance between ever larger and more lethal military assistance packages to Ukraine (eleven so far, totaling some EUR 200 million, including mortars, APCs, a range of man-portable systems, anti-aircraft guns/cannons) and ensuring that Finland, as a frontline state (to use NATO parlance), is able to defend itself; unlike many less exposed NATO members, Finland cannot 'empty its stores to buy new ones in a few years' time. Nevertheless, Finland's purchases of materiel in 2022 have supported the continuation and opening of production lines that can directly support Ukrainian efforts if the war in Ukraine continues.

-

France

-

Camille Grand, Distinguished Policy Fellow, European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)

France has traditionally been the strongest proponent of European defense since the signing of the Brussels Treaty in 1948, although the definition of 'European defense' has fluctuated over the decades, including in recent efforts to develop and refine the concept of 'strategic autonomy.'

From a French perspective, the Russian war on Ukraine is a defining moment for the European defense agenda. On the one hand, it puts to the test many core French beliefs, as it once again highlights the dependence on the United States, given European military shortfalls and many dependencies on US critical capabilities and stockpiles. On the other hand, it makes the case for a much more robust European defense in a degraded strategic environment and vindicates the French view that Europeans need to do more across the board. It also reshapes the institutional environment of the EU and NATO in many ways, with a new focus on collective defense and defense capabilities. The paradox, however, is that despite recent decisions to maintain a robust defense effort until 2030, French defense policy is only marginally evolving in light of current events.

The Geostrategic Landscape: New Realities Viewed from Paris

France and the New Security Environment

Altogether, the French authorities did not experience a watershed moment and did not have to argue for some form of Zeitenwende, as they would claim that France never ruled out the major conflict scenario in Europe. Hence, France has been investing in deterrence and defense over the years when many Europeans were cashing in the peace dividends and moving away from collective defense or from defense altogether. This view is substantiated by several facts:

French defense spending, while under pressure, never declined to a breaking point. The reinvestment in defense started in the mid-2010s in the context of a wave of terrorist attacks and to support a high pace of operations in the Sahel region primarily. Under the fully implemented 2019-2024 Military Programmatic Act aimed at „repairing” the armed forces, defense spending has been sustained over time, bringing the budget back to the two percent of GDP NATO benchmark before the 2022 Russian war in Ukraine. The future Act covering the 2024-2030 period intends to „transform” the armed forces. Altogether, this means a doubled French defense budget over a decade. The French force model retained a high degree of readiness and some robust capabilities, even though its ability to deliver mass or sustain a major conventional engagement over an extended period of time was increasingly questionable in multiple capability domains given the focus on demanding but limited crisis management operations over the past decades. The French long-term investment in its independent nuclear deterrent has been sustained over decades and has always been connected to the risk of conflict involving a major power.

For their part, manufacturers have also committed to significant production accelerations concerning priority equipment.[4] While not revolutionary, these announcements and „commitments” acknowledge the need to address previous industrial shortfalls through a series of concrete steps.

The first available information on the new „Military Programming Act” suggests some consistent priorities „to improve the balance between equipment, maintenance, ammunition, operational activities, and logistical coherence, consolidate support services that have in the past been cut back too often, and strengthen our health services“ with the move to the „sole use“ of the Rafale aircraft, „increase our capabilities in all areas of air defense by at least 50 percent; that of course includes anti-drone combat“, a focus on space as a domain, and „naval capabilities which are commensurate with our country’s maritime assets.“

Renewed Opportunities for Cooperation