|

German and EU companies need contingency plans for continued operation in the case of major geopolitical and economic disruptions. |

|

Governments and companies must review the excessive concentration of risks for specific products and sectors. Corporate risk management alone is insufficient and industrial policy measures are required. |

| Governments must consider national security concerns for specific products, technologies, and critical infrastructure. |

Please note the web version of this policy brief does not include footnotes. To see them, please download the pdf version here.

Introduction

The rise of China in recent decades has been an economic success story, both for China and for the world. Yet, as China becomes increasingly repressive and the role of the state grows stronger, some in the EU are calling for reducing trade and investment with China by shifting to “friend-shoring” – sourcing supplies from allies – or even “homeshoring” – shifting to domestic production.

Both approaches would not only be costly but could even increase risks and render the EU economy more fragile. China is an important trade and investment partner that contributes significantly to economic gains, creating jobs and affordable goods for Western businesses and economies. China is also an important producer of technology, some of which is essential for Europe’s green transition. While untangling economic integration may reduce some risks, the loss of diversification may pose others. From a geopolitical point of view, arbitrary friend-shoring concepts could exclude many developing countries as business partners, including strategically important ones. In short, a shift to friend-shoring would bring more problems than solutions.

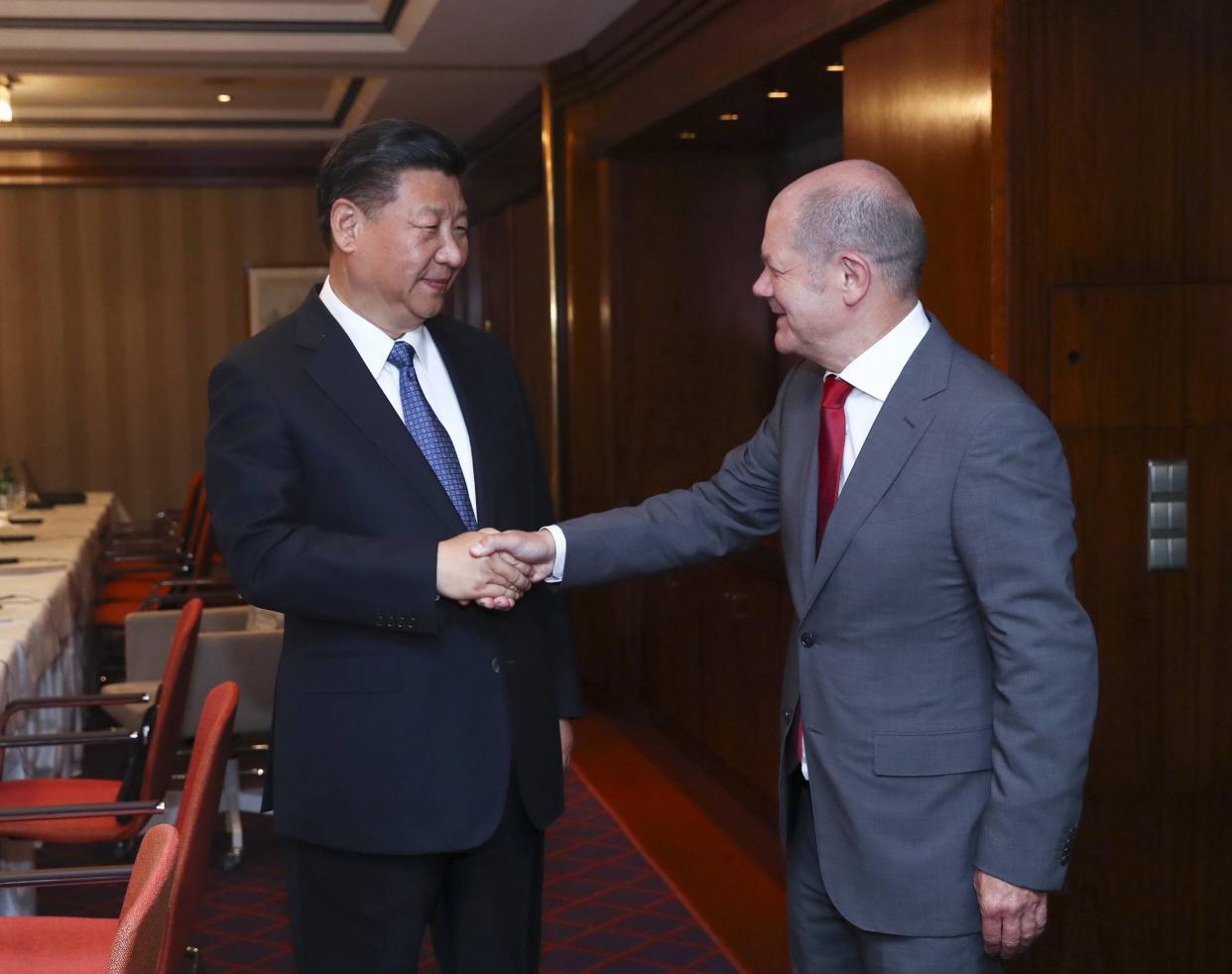

Yet, maintaining the status quo is not an option. This is a message German Chancellor Olaf Scholz must convey on his visit to Beijing in November – the first by a G7 leader since the pandemic began. European unity will be key, so it would be a serious mistake for Scholz to simply continue with the policy of Wandel durch Handel (change through trade), which was a hallmark of former Chancellor Angela Merkel’s era. Aside from significant economic costs, China’s economic and government model creates geopolitical risks that are now too big to ignore. Germany and Europe should develop a measured and unified response, focused on managing large economic risks resulting from major geopolitical disruptions.

Instead of framing the debate around concepts such as friend-shoring, we propose a three-pronged strategy based on (1) corporate risk management induced by clear government messages, (2) a reduction of concentrated risks related to excessive dependence on specific goods and a review of critical security risks of goods with dual civilian and military use and critical infrastructure, and (3) a modernized approach to industrial policy.

The State of Trade and Investment Relations

World trade volume and value have expanded dramatically since 1995 when the WTO was established. China has been an important factor in that growth (see Figure 1). China’s economy has been expanding at impressive rates over the last decades, substantially increasing its share in global GDP to levels close to that of the US. Consumers around the world have benefited from inexpensive Chinese products and close to 800 million Chinese have been lifted out of poverty over the last 40 years. European and German companies have exported to China with significant benefits for shareholders and workers.

However, defining relations with China through trade alone is an outdated approach. Integration with an economy in which a single party dominates the government and many companies creates economic and political costs for trade and investment partners. And this economic model is at odds with the implicit and explicit assumptions that underlie the initial agreement for China’s WTO accession. China’s economic growth prospects have cooled substantially and official statistics on its economic performance have become more biased, suggesting that growth prospects may be much less favorable than generally believed. China’s zero-Covid strategy has led to severe supply chain disruptions. Finally, there are geopolitical uncertainties to consider, for example in relations with Taiwan. When dealing with China, economic benefits must be weighed against these costs. German and European businesses face difficult choices as geopolitical tensions rise.

EU-China Economic Interdependence

The EU and the China have a strong trade relationship, which has expanded substantially in recent years (see Figure 2).

With exports valued at 224 billion euros, China was the third-largest market for European goods (after the United States and the United Kingdom) and accounted for 23 percent of total EU exports in 2021. China is also the second-largest export destination for Germany after the US. Germany accounts for more than 45 percent of EU exports to China. Regarding imports to the EU, China ranked first (473 billion euros). Altogether, China is the EU’s most important trading partner, and the EU runs a significant and growing trade deficit with China.

There is no sign of decoupling in merchandise trade – on the contrary, trade has increased again substantially in the last year after a slowdown during the Covid-19 pandemic. The pandemic led to a decline in international trade in goods in the first half of 2020. However, EU imports and exports recovered and reached a record high in 2021. In contrast, the EU runs a surplus in services trade with China.

Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) in the EU (including the UK) peaked in 2016 (47.4 billion euros) according to the Rhodium Group but has declined since then. In 2018, Chinese investment fell to 20.3 billion euros and dropped to 10.6 billion euros in 2021, the lowest year since 2013 (when excluding the pandemic year of 2020). It is unlikely that Chinese investment will recover in 2022. The decline can largely be explained by a change in Chinese economic policy, increasing outbound investment controls, strict capital controls and Covid-19 restrictions. Other factors are the war in Ukraine and strengthened screening mechanisms in the EU, both on a national and European level.

In terms of European investment in China, two trends have become more pronounced, according to the Rhodium Group. The first is a stronger concentration of European FDI with regard to companies and sectors: The top 10 percent of investors made up 80 percent of all European FDI in China in the past four years (2018-2021). In addition, five sectors – autos, food processing, pharma/biotech, chemicals, and consumer product manufacturing – account for nearly 70 percent of all FDI. The second trend is a stronger concentration of countries. Over the past four years, only four countries – Germany, the Netherlands, the UK, and France – made up 87 percent of total investment on average. And among these, four German companies alone – Volkswagen, BMW, Daimler, and BASF – contributed 34 percent of all European FDI into China by value from 2018 to 2021. While a few large companies (often German) are increasing their investment in China, many other companies are refraining from new investments. The aim of these new German investments is to produce more locally for the local market. And while companies are generally regionalizing production to protect supply chains from disruptions in different parts of the world, Chinese authorities are also pressuring companies to do so in order to ensure technology transfer.

China – Still Partner, Competitor, and Rival – But Rivalry Intensifies

The United States has a clear approach to China: The country is a non-democratic rival that threatens US economic, military, and technological power and dominance. With its “Made in China 2025” industrial strategy, Beijing is actively promoting key sectors of the economy to become a technological superpower – at the expense of others such as the US.

The EU has also changed its attitude since adopting its China strategy of May 2019, which describes China as a “cooperation partner, economic competitor, systemic rival.” This characterization still holds true in general, but China’s complicit support of Russia’s war, among other things, means that Germany and the EU need to reassess their approach to China further. Of the three pillars, the trust basis for “partnership” has eroded while “systemic rivalry” has intensified. A major crisis regarding Taiwan is a geopolitical risk with big political and economic implications for the EU. And when it comes to EU-China collaboration on major global public goods such as climate change and pandemic prevention, the last years have not been easy.

The EU has developed several unilateral tools to deal with China as an “unfair” economic competitor and to level the playing field in economic terms. In the area of trade, the EU has introduced several so-called autonomous instruments to counter negative effects from China’s economic model – in particular, the large role of the state and the Communist Party. This includes the introduction of investment screening at the European level, an anti-subsidy instrument, and an international procurement instrument (IPI). The EU is also developing an anti-coercion instrument to address China’s coercive trade practices, such as those used recently against Lithuania in a dispute over a de facto Taiwan office in Lithuania.

In addition, the relaunch of EU trade policy with a focus on enforcement (February 2021), a coordinated EU industrial policy (e.g., the European Chips Act of February 2022), its connectivity strategy, and digital strategy all show that the EU wants to better position itself to compete with China.

Gauging the Magnitude of a Trade War with China: Concentrated Risks and Dynamic Effects

As geopolitical risks increase, several studies have tried to gauge the potential costs of a trade war or even decoupling for Germany and the EU. The standard trade models come to costs of 0.5-1.5 percent of GDP. While this would be significantly higher than the cost of trade barriers resulting from Brexit, this number would not lead to a catastrophic meltdown of the German and EU economies. There are three simple reasons for the relatively muted overall trade effects. First, trade models allow for the diversion of trade to other trading partners. As trade with China is penalized in a trade conflict, companies can dynamically adjust over time and trade with neighboring countries, e.g., in the ASEAN region.

Second, trade models cannot easily capture disruptions in value chains resulting from very concentrated risks in specific, specialized products. In a confrontation over Taiwan, supply chains for some critical inputs would be severely disrupted. TSMC in Taiwan, together with South Korea’s Samsung, hold a duopoly for high-end chip fabrication, for example. A possible disruption of world supply would affect major value chains in which chips are critical and very difficult to substitute. The resulting macroeconomic costs could thus be higher.

Third, investment stocks and related production capacities are not captured in the trade models but are important for companies. Many big German companies in the car industry (particularly Volkswagen, BMW, and Daimler) not only export but also have major production sites in China (see chapter on economic interdependence). While GDP may be less affected by risks to investments, shareholders of companies would certainly take losses in case of a major conflict compared to a non-conflict situation. Such possible losses should, however, already be priced into stock markets.

Finally, dynamic benefits resulting from trade via innovation processes are not captured by static trade models.

Overall, the risks to value added in Europe and Germany may be larger than trade models suggest, because value chains can be exposed when alternative suppliers are rare.

Still, the economic effects of a potential geopolitical escalation would not necessarily be critical for China, for whom the EU represented only 15.4 percent of its exports in 2021 (US: 17.1 percent). Policymakers should therefore shed the illusion that China would refrain from a major geopolitical or security decision to avoid economic damage.

Recommendations

Before Chancellor Scholz’s visit to China, Germany and the EU need to evaluate their approach to China. Most importantly, European unity is key. All too often, visits by individual heads of government have been used by China to weaken European unity. Since the Lisbon Treaty, the EU has the exclusive competence in both trade and “foreign direct investment” so that international trade and investment treaties cannot be negotiated by the German chancellor. It would be useful for Chancellor Scholz to distance himself clearly from his predecessor Angela Merkel and to reassure EU partners in this regard. We propose three main recommendations.

1. Improve Corporate Risk Management Through Clear Government Messages

Supply chains are made by companies, not governments. Governments can only create conditions for companies to operate and provide incentives to make them more aware of geopolitical risks. This requires clear political messages at the highest level, including when CEOs participate in government trips to China, that the exposure of stocks to geopolitical risks remains with shareholders. This has been by and large the approach as more than 1000 international companies withdrew from Russia in the wake of its Ukraine invasion. The big difference regarding China, however, is that the balance sheet risks for some companies are considerably higher than in the case of Russia.

Beyond managing balance sheet risks from direct exposure, companies need to ensure business continuity in the case of a major geopolitical conflict. This often requires duplicating essential parts of value chains.

A critical review of current financial guarantees, which can create incentives for excessive corporate risk taking, would send a clear government message. A tougher approach to external investment guarantees, such as that contemplated by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, is needed. Policymakers should remove state investment guarantees for operations in China and other countries. Geopolitical risk assessment would become more imperative if businesses faced the threat of Chinese coercion.

Governments can also issue regulations to restrict trade with autocracies that disregard human rights. Existing EU responses include the proposed ban on imports from forced labor (September 2022), and the Due Diligence Act.

The most effective response to deal with high exposure to China is diversification. Australian businesses, which have been directly subjected to Chinese coercive economic measures, have already advanced down this path. They are increasingly implementing the “China plus one” strategy, which means diversifying businesses and supply chains to alternative destinations beyond China. Australian companies are also building critical industrial capacities that are not dependent on Chinese imports. This is an important lesson for European companies.

Governments can support corporate boards to diversify trade and production by negotiating and implementing ambitious additional EU trade agreements. Such agreements facilitate bilateral and regional trade by lowering trade barriers and increasing trade and investment access to markets. According to the European Commission, EU exports under Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) surpassed €1 trillion in 2021. In addition, between 2020 and 2021, European exports to preferential trading partners (minus the UK) grew more (16%) than European exports to all trading partners (13%).

It should therefore be a top German priority to support the EU in advancing FTAs. The next steps for EU trade policy should be the fast ratification of the EU’s Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with Canada (by Germany) so that the agreement can be fully applied. At the same time, modernization of the agreements with Chile and Mexico, as well as new free trade agreements with Australia and New Zealand should be concluded and/or ratified quickly. Other geopolitically and economically important trading partners for the EU are Indonesia and Mercosur.

In this context, it would also be important to provide incentives for partner countries to create new industrial clusters so they can develop interlinking supply chains. This is often the case in China and should also be built up in other partner countries to ease diversification. In negotiating trade agreements, the EU should be ready to open its markets further, also in advanced products, to make trade agreements more attractive for developing countries.

2. Bolster Supply Chains by Reviewing National Security Risks and Excessively Concentrated Risks

The most important political and economic task is to remain committed to an open and global world trading system despite the difficult geoeconomic environment. Otherwise, an increasingly fragmented trading system will lead to more uncertainty, less ability to absorb shocks and possibly to a global recession. This means we need strong global rules and institutions like the WTO to facilitate trade and mitigate global trade and investment conflicts. This also enhances the resilience of supply chains.

However, some decoupling is justified on national security grounds. Dual use technologies deserve protection. Moreover, security risks arising from economic integration, for example in the context of IT infrastructure or data management, must be tackled head on. But this requires careful calibration, because decoupling and block-building lead to efficiency losses, reduce innovation, and create new divisions. Fragmentation should be limited as much as possible.

In addition, the EU must critically review concentrated risks. It needs to diversify excessive dependencies on certain critical products in the value chain named in the “Commission staff working document: Strategic dependencies and capacities” from May 2021, updated in 2022.

These critical products, which account for 6 percent of European imports, include, among others, semiconductors and certain rare earths and raw materials that are important for the green transition of the economy. In some of these markets, China currently holds market shares of above 80 or even 90 percent. These constitute major vulnerabilities to the global economy and urgently need to be addressed.

Solar panels are another example of concentrated risk where the majority of global production is located in China. According to Eurostat, China accounted for 75 percent of European imports of solar panels in 2020 (see Figure 3), and this number has only gone up since the start of the war.

Connected to these dependencies is another problem for the EU: The Chinese solar panel industry depends on critical components made in the Xinjiang region using forced labor from the oppressed the Uighur population. The EU therefore faces the dilemma of boycotting to oppose China’s human rights abuses or continuing to source cheap imports of solar panels that enable the green transition in the EU. However, an import ban of products made using forced labor, proposed in September 2022, would call European solar panel imports into question.

Taken together, only a few products are subject to vulnerabilities. They are critical, but the EU should not change its entire trade strategy based on them. Instead, it needs a tailored trade and investment strategy for these products. On the trade side, the EU should remove all import barriers for any raw materials where the EU is overly reliant on single suppliers from China. Moreover, it should negotiate market access for European producers in countries where domestic mining capacity for raw materials is limited.

When it comes to Chinese investments in Europe, critical infrastructure needs to be protected and new excessive dependencies need to be avoided. The recent case of Cosco’s participation in the Hamburg port has been discussed in Rühlig (2022). Moreover, reciprocity in market access is of great importance.

3. Modernize the European Approach to Industrial Policy

China’s competition also constitutes a challenge to German and European industry. China is becoming a major competitor in high-tech and growth sectors, and with its “Made in China 2025” policy, it employs targeted industrial policy to capture larger parts of the value chain. This has created a dilemma for EU and German policymakers, as the EU approach has been for a long time to ensure a level playing field in the single market and prevent national subsidies from distorting the single market. EU institutions and national policymakers such as former German economics minister Peter Altmaier have acknowledged the challenge posed by these major differences in economic models. They have responded with various new approaches such as the Important Projects of Common European Interest (IPCEIs), yet the overall strategy remains unclear.

Targeted (and non-excessive) industrial policy needs to be part of the toolbox to help create new markets and products in which Europe is a leader. China and the US have both increased their government support policies to develop and grow industries such as green hydrogen, chip production and others. Yet merely copying the Chinese approach would not do justice to Germany and Europe’s strengths. Also, the industrial policy strategy proposed by Germany’s Altmaier was not a good model to develop the country’s industrial strengths and was rightly and widely criticized for being inconsistent with a market economy and for harming domestic consumers. A new approach to industrial policy is necessary. Basic research, education policy, improved business conditions, and the development of risk-capital markets must be a central part of that strategy.

There is no need to despair. China’s economic growth has been extremely impressive during the last decades but signs are increasing that the era of high Chinese growth is drawing to an end. China’s working population is shrinking and will shrink substantially in the next decades due to demographic change. Capital investments have been rather unproductive as of late, with real estate problems just one visible sign. The success of China’s technology policy is subject to debate but may well be overestimated.

Conclusion

Instead of reducing economic integration in general, we recommend deepening global economic integration with countries outside China. Diversification will make the economic system and supply chains more resilient in the face of geopolitical shocks and generate new growth benefits.

Germany and the EU are facing increasing costs and uncertainty in dealing with China. We therefore believe that companies should address their operational risks resulting from geopolitical tensions. Corporate boards must make business continuity in worst case scenarios a top priority. Governments should support diversification strategies with new trade deals while avoiding financial incentives and insurance benefits for activities in China. Decoupling in security-sensitive areas is important. Finally, we emphasize that the development of a targeted and non-excessive industrial policy strategy is needed. A strengthened common market, innovation, and improved domestic investment conditions are crucial for Europe to counter Chinese competition.