The COVID-19 crisis has led to what many felt was a ‘shock digitisation’ of the world: in a matter of weeks, all day to day activities had to be digitised to support working from home and to maintain social distancing.

Political institutions, schools, and companies moved their operations online. Governments started to hold cabinet meetings via video conferencing platforms, and international summits and face-to-face meetings of the UN Security Council and EU Council were replaced by video calls.

UN Security Council meets online. Source: Al Jazeera English via Twitter, 25 April 2020

Some think tank outputs (like social media outreach and web publishing of policy papers) were already digital before COVID-19 hit. But an essential part of our work was not. The majority of political consulting, background briefings, workshops, and conferences still happened face-to-face. Hence, when lockdown came – and shock digitisation with it – many of us have been treading new terrain.

Many think tanks, for the first time in their history, introduced mandatory telework, restricted travel, cancelled all in-person events, organised online staff meetings, and stepped up their digital game considerably.

Source: GMF Newsletter

While going digital certainly comes with many benefits (such as scalable outreach via social media, and increased productivity due to Cloud and collaboration platforms), it also comes with IT-security risks.

Risks include the loss of confidential information due to hacking or data breaches, as well as disruptions to digital infrastructures due to configuration errors or hacking.

What’s more, during recent years think tanks and political foundations have become, as Microsoft warns, the focus of foreign intelligence agencies. And now, even less-sophisticated actors are starting to engage in cyber espionage, including Iran, Saudi Arabia, North Korea, and Turkey. The Snowden leaks also remind us that in the intelligence world there are no friends, only partners, so even spying among allies can be expected.

This left many of us wondering how to secure the digital transformation of think tanks and how to boost IT-security.

Generally speaking, IT security deals with:

- confidentiality (no unauthorised users should have access to information),

- integrity (protecting information from unwanted deletion or modification), and

- availability (your data/services are available to you all the times).

In this series, we want to take a closer look at the security challenges posed to think tanks by this new situation, and provide both technical background information and practical advice for how to create safer spaces for sensitive conversations online.

It will also be great to hear about your own experiences and exchange good practices! Please don’t hesitate to get in touch and let us know how you have been dealing with this.

The cybersecurity for think tanks series:

- Part two: Know your Risks, Threats and Set Up

- Part three: What to Do

- Part four: The Bright and Dark Sides of Zoom

- Part five: How to Create Safer Spaces for Sensitive Conversations Online

Part 2: Know your Risks, Threats and Set Up

The more aspects of your day to day operations get digitised, the more important IT-security becomes. The risk of a fast-paced ‘shock digitisation’ is that security becomes an afterthought, because in the short-term, functioning systems are more important than secure ones. But IT security, in general, is a long-term process and not a quick fix.

It’s also a team sport. The day-to-day behaviour of all staff impacts your security level. For example, if your employees are unaware of risks or untrained in dealing with phishing emails, they are more likely to click on a malware attachment and compromise your entire operation. It is often said that IT security depends on the weakest link in the chain, whether that’s insecure software or users.

Being a team-sport depends on the coach too. Until recently, IT security did not rank too highly on the priority lists of executives, because spending money on threats that might never materialise seemed rather unattractive for cost-conscious organisations. Fortunately, more executives have become aware that they must up their IT-security game.

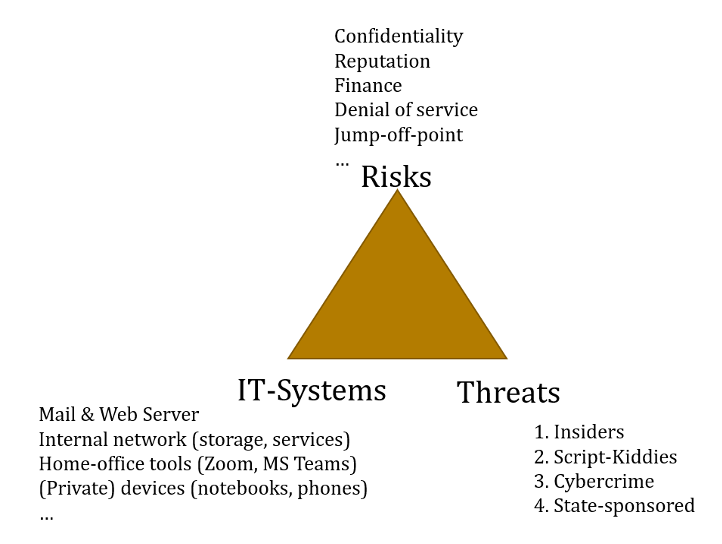

Of course, not all think tanks are alike and some have stronger security requirements than others. Threat modelling is a practice to tailor security requirements to the particularities of a specific organisation. Threat models are typically composed of risks, threats, and the individual IT-infrastructure set up. IT infrastructure (i.e. the software and hardware you use) has to be tailored to specific risks and threats.

What are your risks?

In IT security, a risk is a potential for loss, damage, or destruction of an asset as a result of a threat exploiting a vulnerability in your IT systems. In other words, it often entails losing something of value. Here, we’ve compiled a list of threats that seems most relevant for think tanks.

In our assessment, the biggest risks for think tanks lie in a loss of reputation. Your reputation, and therefore the trust you receive from the policymakers you advise, the public you inform, or the human sources you rely on, is your most valuable asset. It can get harmed, for example, if an internal communication gets leaked. Remember the ‘fuck the Europeans’ intercept of US Ambassador Nuland in 2014 that was leaked to the press?

Source: BBC News, 7 February 2014

As we move work to video-conferences, a topic we will explore in part four of this series, Zoom calls come with their risks of interception and leaking, or unwanted third parties joining and recording your conference calls.

There are also concrete financial risks for many small and mid-size organisations. There are classic cyber-crime schemes like CEO fraud, where someone pretends to be an executive and orders its budget office to initiate a banking transaction to some dubious entity. If you depend on third-party funding, your financial assets might be at risk if you or your donors get hacked. Remote work also produces unique challenges, as your accounting department may access sensitive accounting systems from insecure private computers at home.

There are also personal risks for your employees or sources. Information could be stolen to blackmail your organisation or individual employees. State-sponsored cyber criminals in authoritarian regimes and countries with limited statehood can also target individuals with harassing tactics like trolling or doxing (leaking personal information such as a private addresses to intimidate and quiet targets or dissenting voices). Often women are particularly targeted by these types of tactics.

And let us not forget vulnerable sources. Think tanks working in authoritarian regimes rely on interviews and first-hand witness reports for their research. In areas where government transparency is low and access to information is limited, whistleblowers are often a primary source. Your sources could suffer if you cannot protect their identity because you use insecure communication channels or your IT system gets hacked. Likewise, if you are involved in Track II diplomatic processes, like conflict mediation between formerly warring parties, the identities of stakeholders might be at risk.

There are also operational risks: work or data could get stolen. For small and mid-size companies this could be the loss of intellectual property due to espionage of internal Zoom calls or the email server.

These reputational, financial, personal, and operational risks can overlap of course.

What are your threats?

A threat is an action or inaction likely to cause damage, harm or loss. A threat is something or someone you are trying to protect against. The following threats, in ascending order, can be relevant for think tanks.

A ‘script kiddie’ could break into your system just for the fun of it (or rather, for the ‘lols’). For example, ‘Zoombombing’ has already happened at many online events where the webinar link was posted publicly on Facebook or website.

A cyber-criminal gang could want to extract money from you by encrypting all your internal files with ransomware and demanding a ransom payment with Bitcoin. Ransomware is an increasing threat in IT security, hitting universities, hospitals, and research institutions worldwide.

As with all emails, invitations to Zoom events can be faked and include ransomware somewhere behind the link to join a meeting. Such a denial-of-service attack would be a worst-case scenario in times of remote work, as it certainly would halt all operations.

An individual or organisation (or a state) could try to shut down your website in retaliation, for example, for a critical paper you published against a government. These retaliation practices are not uncommon. There was a case of doxing in Germany where a single hacker compiled target lists of figures in the public domain, collecting open-source intelligence like addresses and phone numbers, and leaking them to the public because he wanted to send a message.

A disgruntled employee with access to sensitive information is often overlooked as threats. Imagine someone’s contract wasn’t prolonged and now they threaten to sell internal information to the press.

The most challenging adversaries for think tanks are intelligence agencies. Both foreign and domestic intelligence agencies in authoritarian regimes might be interested in you because you work on a specific region or topic of interest, or because you have an office abroad. This has to do with perceptions. You may operate under the assumption that you don’t have anything interesting to hide, no access to sensitive government documents or communications. But think tanks, especially those that are close to the government or receive public funding, are automatically interesting for foreign intelligence agencies. So, think tanks should always assume they are targets.

You could be used as a jump-off point for cyber-attacks by foreign or domestic intelligence agencies to reach other, higher-value targets like politicians. This means attackers are not necessarily interested in you personally, but in the people in higher echelons of power who you might have close contacts with. Thus they could be after your email contacts or use your email identity to send phishing emails or malware attachments to your customers. NATO’s own cyber-security centre in Tallinn was a victim of such a scheme: allegedly Russian state-sponsored hackers tried to use the reputation and credibility of NATO’s Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence to send a manipulated conference agenda to security researchers worldwide.

How is your IT infrastructure set up?

Your IT infrastructure determines your ‘attack surface’ – the ways someone can launch cyberattacks against you. This includes operating systems, software used, and the set-up of internal servers (file-, mail- and web-servers).

At the bare minimum, most think tanks will use some type of email system for internal and external communication, an internal network or storage system to save files, and potentially a website that is hosted somewhere.

Then there are your staff’s devices, the computers, printers, Wifi routers, and smartphones you use in your office. The last part of your attack surface is the software that you use. The more apps, tools, and digital processes you use, the more susceptible they become to hacking.

Source: Matthias Schulze

As you can see, unfortunately, the threat landscape for think tanks is complicated. You realistically can defend against script kiddies and organised criminals that hack for money. This requires some investment in your IT security and is a continuous process. But protection against fully-fledged cyber-attacks by intelligence agencies is hard to achieve, if not impossible.

Now that we’re familiar with the big IT security risks and threats, in part three of this series we look at what you can do to enhance your cybersecurity in the short, mid and long term.

Part 3: What to do

Now that you know what the main cybersecurity risks and threats for think tanks are, what can you do to protect your organisation and create safe spaces for sensitive conversations online? To help you with this process we present some of our lessons learned.

First, it’s important to know that just as there is no 100% safe sex, there is also no 100% safe online communication. All digital conferencing tools can in principle be hacked, either via their servers or via your personal device. Some require more sophistication than others.

Nonetheless, there are important steps you can take in the short, medium and long term to significantly improve your cybersecurity and minimise or mitigate the risks.

Short term: determine your individual threat model and prepare

If you haven’t really thought about IT security before, now is as good a time as ever to start thinking about it.

Since threat models are an interplay of risks, threats, and IT infrastructure, you might want to figure out what your ‘crown jewels’ are – that is the asset that is most valuable to you and the loss of which would be devastating.

For example, it could be your employee’s private information, budgeting, sensitive research materials like interviews with dissidents whose life could be at risk if the information got in the wrong hands, or simply more abstract goods like reputation.

Then you need to prioritise the threats. You cannot defend against every scenario because you likely have limited resources. Focus on those threats that are manageable. Unfortunately, you cannot realistically defend against state-sponsored hackers that are really advanced.

You also need to get to know your internal network topography or IT landscape. What systems do you have, what software do you use, where is sensitive stuff stored, and who has access to it? What devices can access what part of your internal network? Make sure you know which parts of your systems face the web (i.e. are accessible via the internet). These are the most likely targets for cyber-attacks. This might include your web server, email, and potentially cloud or collaboration platforms.

This is a cumbersome process, but necessary. If you start adopting new tools, apps, and techniques, before having figured out your threat model, you might choose tools that do not fit your needs.

If you are unsure about your threat model, many national cyber-security centres offer advice for think tanks. In some countries, there are specialised programmes or ‘cyber alliances’. So, reaching out to others is generally a good idea. You can even hire ‘friendly hackers’ called penetration testers, that will test the IT security of your systems and give you advice, for a fee.

Medium term: harvest the low hanging fruits first

After you have thought about your threat model and understood your network topography, you can start to fix some low-hanging fruits – these are the attack vectors that are often exploited but relatively easy to fix.

- Have backups. If you have duplicates of your most important data, loss of integrity and availability can be compensated more easily. Ideally, you have an off-site backup in case a fire burns down your office. If you rely on ISO certified cloud storage providers, they can guarantee regular backups.

- Segregate your networks. Your ‘crown jewels’ should be hosted on a different network to your day-to-day stuff like research notes or emails. You should erect access control barriers around this segregated network, making sure that only essential personnel can access this area. You also might want to physically segregate your guest Wi-Fi from your internal Wi-Fi network. And while you are at it, make sure there are no easily accessible ethernet or USB ports in your office.

- Make sure you update your software regularly. Most hackers exploit known software vulnerabilities. This can be avoided if all your systems have up-to-date software. Make sure you run operating systems that still receive regular security updates. IT security is not just about technology, but also about policy and processes. For example, if you have a policy that employees can bring their own device into your network, then you shift responsibility to them. Now you must make sure that you have a process whereby your employees regularly install updates to fix software bugs that can be exploited by hackers. In turn, if you have a more centralised approach, where your IT-team manages updates, responsibility rests with them.

- Use two-factor authentication. Bad passwords are a primary vulnerability. With two-factor authentication, for example via your smartphone, you add a second token that is required to log-in to your accounts. While hackers can easily steal your password, it is way more complicated to steal that second factor, like a randomly generated number that changes every 60 seconds. Two-factor authentication prevents a lot of phishing schemes and thus is a relatively easy security measure that goes along way. Most commercial platforms from Google, Microsoft, or Twitter have two-factor authentication that can be activated. If your system is self-hosted, this might be harder to set-up.

- Set up encrypted communication channels. If you rely on email to get in contact with sources, set up PGP (Pretty Good Privacy), a plugin to encrypt emails. If you use messenger apps on your smartphone, use Signal instead of WhatsApp. Remember that open source tools tend to have better privacy and security profiles because the source code can be inspected by researchers for hidden capability.

For more information and best practices check out Tactical Tech or the Electronic Frontier Foundation, who compile useful digital self-defence techniques for journalists and NGOs worldwide. For example, you could install ad blockers and anti-tracking plugins to prevent large Internet companies from tracking you. You also might want to check out the security planner by the Canadian tech security think tank Citizen Lab that helps you to create a threat model.

Long term: invest in IT security and employee awareness

- Make IT-security a CEO-matter. IT security is no quick fix. It is a long-term process that requires constant adaptation. There is a saying: ‘there are only two kinds of organisations: those who got hacked and those who don’t know they got hacked.’ This is of course a matter of money and priorities. If you depend on external funding, ask your funders to increase your IT budget. If you can, hire a chief information security officer, but they do cost!

- Develop a plan to protect your IT and react in case of emergencies. You need something like a fire-emergency plan describing what you will do if you get hacked. This should outline your communication chain: who calls who, even if your communication system is offline or the IT department or system administrator is on vacation. It also includes a situational awareness about your attack surfaces, i.e. the networks, devices, and software you use.

- Train your users and employees in general IT hygiene. For example, spotting phishing emails and using diverse passwords for different services. This will require constant training.

- Other policy-related questions to ask are about where you store data. Do you host all of your services locally or are you completely dependent on third-party cloud apps like Google’s Productivity Suite or Microsoft’s Office 365? If the answer is yes, you out-source security to these providers. This may be a relief for some think tanks, but a no-go for others who have stronger confidentiality requirements. Remember that the cloud is just someone else’s computer and uploading sensitive internal information to US servers might not be in your interest since it can be accessed with lawful interception orders.

We hope this advice will be useful to your think tank. Remember, this is a marathon not a sprint. In the next part of the series, we explore the bright and dark sides of Zoom and how you can create safer spaces for sensitive conversations online.

Part 4: The Bright and Dark Sides of Zoom

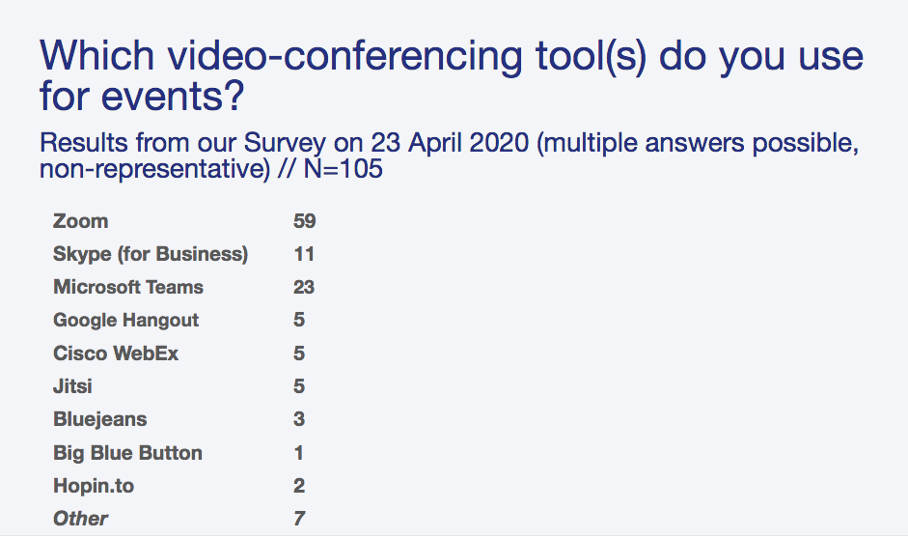

In mid-April, during a web event in our #DigitalThinkTanking series, we surveyed thinktankers on which video-conferencing tools their think tank uses for online events. This is what we found:

In other words: an overwhelming majority of think tanks use Zoom.

The results of our quick survey also seem to fit in with the global trend: Zoom surpassed many established video conferencing services like Microsoft’s Skype, Cisco’s Webex or Google’s Hangouts in terms of popularity.

In late March 2020, Twitter and social media feeds were suddenly full of screenshots showing Zoom work meetings, Yoga classes and after work beers online.

Many policymakers jumped on the Zoom bandwagon too – especially in those countries where the public sector ‘overslept’ the digital transformation (for example, where labour laws regulating public officials and workspaces had not been updated in years to allow for remote work, or where there’s no established or trustworthy way to cast votes remotely).

In the digital world it is often the tools that are particularly easy to use, that focus on a single task, and that have low barriers to entry, that attract a lot of users. Security is often an afterthought.

Once user adaptation is widespread, network effects kick in making it unattractive to use alternatives to the most popular option. This has been the case with Facebook, WhatsApp, and now Zoom. This network effect leads to a cascading effect, meaning even more users and latecomers to digitisation – like governments – join the platform too.

With high popularity comes the bad guys

‘Zoombombing’ – the practice of pranksters joining Zoom sessions without the password – soon became a thing.

This was facilitated by a lack of awareness by new Zoom users. Posting screenshots of your meetings on Twitter that show the meeting ID allows anyone to join the call. This led the FBI in the US to issue a warning that everyone should set up passwords for their meetings. And in the UK, Prime Minister Boris Johnson accidentally shared the Zoom Meeting ID for a cabinet meeting.

Source: Pippa Fowles/10 Downing Street via Metro UK, 31 March 2020

The Zoom trend did not go unnoticed by intelligence agencies either. Chinese state hackers allegedly began to target Zoom calls of companies to siphon intellectual property. With more governments conducting day-to-day business via Zoom, this should not come as a surprise. The sudden popularity of the app made it worthwhile for intelligence agencies to invest time and resources to spy on digital meetings. Like most hackers, intelligence agencies tend to go where the users are, because the return on investment seems highest.

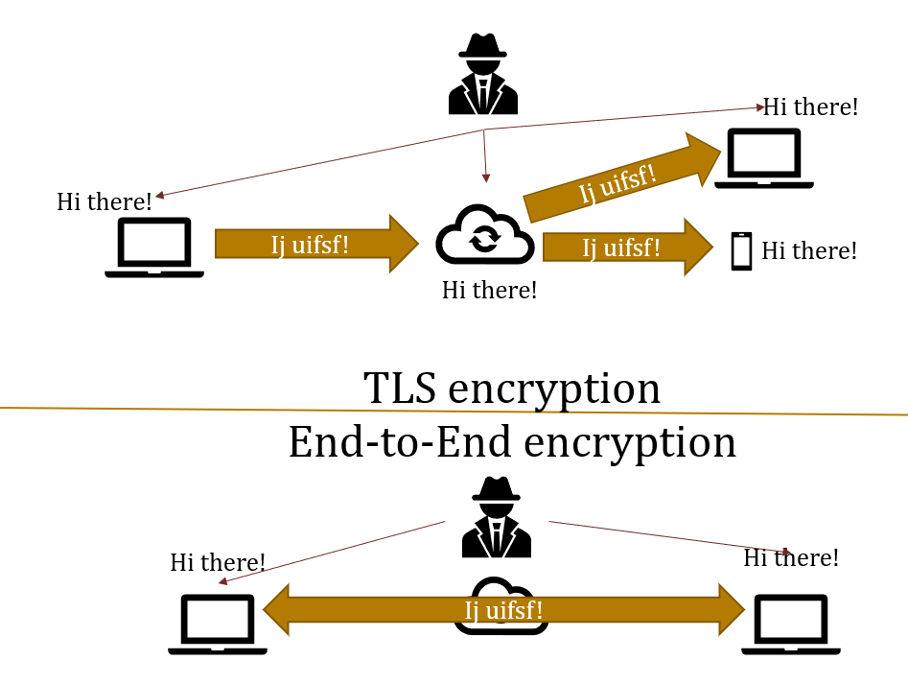

The company Zoom actively contributed to this trend, as it made false promises about its security practices. A report by the Canadian Citizen Lab uncovered that, although advertised on its website, Zoom did not use the industry gold standard of end-to-end encryption.

Instead it relied on transport layer security (TLS), which has one important loophole: communication via two parties is only encrypted while in transit from each user to the server, but not while it is processed on Zoom’s servers.

Zoom uses intermediary servers sitting in between users to do audio processing and signal enhancing. This is essentially the key to Zoom’s unmatched scalability and ability to host meetings with hundreds of participants, while maintaining excellent audio quality. The caveat is that this allows spying on sensitive conversations via these central servers.

Source: Matthias Schulze

Another contributing factor was Zoom’s start-up heritage. Zoom is considered a unicorn company, one of the few start-ups that become a successful multi-million business in just a few weeks.

The standard slogan ‘move fast and break things’, that is still the prevalent mindset in the start-up culture, has the unfortunate downside of ill-security practices. Launching a limited product quickly is more important than the cumbersome and slow process of adding security during the design process.

Zoom showed lots of signs of this sloppy approach to security: malware-like behaviour of the Zoom client, unwanted data sharing with Facebook and looming security vulnerabilities. Zoom’s CEO Eric Young was forced to publicly apologise and in response promised a stronger focus on security in the future. Since then, the company certainly has upped its security game. For example, in June, Zoom announced that is working on end-to-end encryption. But IT security is a marathon, not a sprint.

Zoom’s security blunders left many in governments and think tanks wondering how secure it is to use video conferencing tools. Some countries or government agencies outright banned the use of Zoom, among them the US Senate, the German Foreign Ministry, NASA and the Australian Defence Force.

Many of those who banned it refer to fears of Chinese cyber-espionage and, particularly in Europe, uncertainty about data being hosted on US servers and thus out of reach for the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (although it is now possible to choose Europe as a server location for Zoom).

If services are hosted on foreign servers there is always the risk that a company is forced to open up their systems for law enforcement or intelligence agencies (lawful access). That risk gained prominence in the debate about potential ‘backdoors’ in Huawei 5G network equipment. However, the Snowden leaks remind us that lawful interception and mandatory surveillance backdoors are being implemented in democratic countries too.

Of course, Zoom is still a reasonable choice for some purposes and organisations. In part five of this series, we go into more detail about how you can create safer spaces for sensitive policy conversations in terms of confidentiality and cybersecurity… including with Zoom.

Part 5: How to Create Safer Spaces for Sensitive Conversations Online

Many think tanks are in the business of ‘off the record’ meetings and confidential policy advice. After all, this is one of the central offers we make to policymakers: we create safe spaces to think through and discuss an idea before it goes out into the open.

Some of us also work on particularly sensitive topics such as defence policy, peace negotiations or cybersecurity. We might engage in sensitive diplomacy, articulate evidence that is unpopular with our own government, or do research on authoritarian regimes where our speakers and participants may fear retribution for speaking out.

In face-to-face events, therefore, we have rules and norms to ensure confidentiality, e.g. the famous Chatham House Rule that restricts the attribution of statements to speakers. These work great in analogue settings.

But is there a way to ensure at least some level of confidentiality – and therefore security – of information at a time when, due to the COVID-19 lockdowns, many think tanks have had to move their operations online?

Choose the right tools for your purposes and the security needs

As threat models are highly individualistic, there is no one size fits all approach. The think tanks we spoke with tend to use different tools for different purposes and needs.

Therefore, first you need to define these purposes and needs. For example, if confidentiality is your core value, and more important than public outreach and media visibility, then certain options are off the table. If you are a highly event-driven think tank with lots of conferences and webinars, functionality may be more important than top-notch security.

As a general advice we found:

1. For sensitive one-to-one meetings with external parties

If you want to do sensitive, one-on-one political consulting with external partners your best options are open-source tools that use strong end-to-end encryption and cannot be easily strong-armed by governments.

Good indicators are if a company publishes transparency reports about lawful access requests and how quickly it responds to reports about published vulnerabilities.

The downside of these tools is that they rarely scale to include a large audience, often are somewhat less-intuitive to use, and are not as popular. Smartphone messengers like Signal or Threema are a top-choice.

2. Sensitive video conferencing within the organisation

If you want video conferencing for internal communication, including sensitive issues such as budgeting or recruitment, you need a compromise between tools that integrate well into digital work environments and those that offer a reasonable degree of security.

Self-hosting a platform like Jitsi or Big Blue Button may be a preferred option for security and data control, but might struggle in terms of reliability and quality, especially if your Internet connection is not great and you don’t have resources for dedicated servers.

Commercial systems like Microsoft Teams/Office 365 or Cisco Webex offer high quality, reasonable security and an excellent integration into other digital collaboration tools like internal chat, project management and more. These tools can be found in early-digitised government agencies too.

If you go for them, make sure you sign up for the business version where you tend to have better encryption and data protection standards. If you are located in Europe, pick a provider that allows you to sign a data processing agreement under the General Data Protection Regulation. Depending on your resources, you also could use both a commercial and an open-source system as a backup.

3. Public events

For larger public events, like conferences or webinars, Zoom is still a reasonable choice. It offers most relevant functionalities like webinar and meeting modes, screen-sharing and break-out sessions. The easy onboarding process and high user adoption make are also attractive.

Video-conferencing is a dynamic market with lots of competitors. Microsoft and Google have also upped their game. So be flexible, as market trends and user adoption might change. Also consider that not all tools are commercially available everywhere. If you work on or in countries such as Belarus and Sudan, you or your partners might not be able to use Zoom due to US sanctions and export restrictions.

If you are using Zoom, send all employees a ‘first aid kit’ to improve security

If you are already using Zoom, as a quick fix you can develop something like a security ‘first aid kit’. This essentially is a list of best-practices to set up Zoom calls securely and avoid ‘Zoombombing’:

- Educate your team when to use what tool. Zoom may be good for public meetings, but for internal or small meetings with external participants, it may be preferable to use Microsoft Teams (if you have it) or your secure back-up alternative.

- Never share the link for participating in Zoom webinars publicly. Not on Facebook, nor on your website, because this invites intruders. Send the link directly to participants after registration with a note not to pass it on.

- Do not make the webinar or meeting public. Use a password as default. Consider sending the password in a separate email to the one with the participation link.

- Always lead the webinar/meeting in a team of two. One team member acts as the conference guide, the other as a behind-the-scenes moderator and community manager: managing the waiting room, collecting comments and questions from the chat. The moderator also can kick-out potential disturbers. This way you can keep a better overview and support each other.

- Use the waiting room for your Zoom event, so you (or someone from your team) can check each person that wants to enter and let them into the room one-by-one.

- Restrict rights of interaction at events, including functions like microphone, video, chat and screen sharing.

- Block the webinar/meeting after the start so that no one can open the link.

- If you do find uninvited guests in your meeting, address the fact head on and announce that you are removing the interferer from the meeting.

- Last resort: end the meeting!

Some last words

These are some of the ideas, tricks and techniques used by think tanks we spoke to while collaborating on this topic. Keep in mind that there is no one-size fits all and that you may need to adapt what you read here for your particular situation. A few additional resources shared by think tanks include:

A comparison of online collaboration tools.

- The Microsoft AccountGuard for Microsoft Office 365 users that are concerned about threat by nation-state actors.

- In-kind software donations for NGOs in Germany (it might be worth looking for similar initiatives in other countries).

- Recordings of all #DigitalThinkTanking events.

Please let us know what you and your organisation has done to boost IT-security while working remotely. We are interested in further tips, comments or even first-hand testimonials from your organisation.